Historian Examines Japan’s Unexpected Alliance with Nazi Germany

By Ann Lyon Ritchie

Scholars continually puzzle over Japan’s alliance with Germany in World War II.

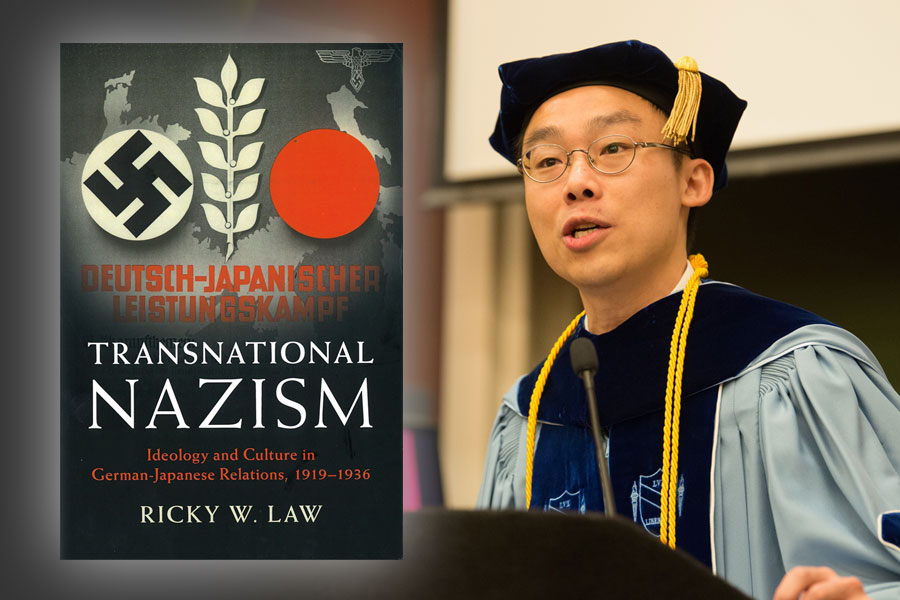

Carnegie Mellon University’s Ricky W. Law connects the dots between the two national powers in his new book, “Transnational Nazism, Ideology and Culture in German-Japanese Relations, 1919–1936.”

“The big question I wanted to address was how Germany and Japan became allies before the Second World War under the aggressive and anti-foreign tenets of their governments” Law said.

Law examined cultural and media outlets of Germany and Japan leading up to the pact that created the Tokyo-Berlin Axis. The book is the first of its kind to draw sources, such as newspapers, films, magazines and text books, from three languages.

“I found that even before the governments of Japan and Germany founded an alliance in 1936, intellectuals and commentators were publishing material that put the other country in a positive light,” Law said.

By examining their writings and broadcasts, he was able to trace a growing mutual admiration between the two nations that was more evident in their cultures than their diplomacy.

In the culture of Japan, commentators admired Germany’s respect for military might, expansion of territory and charismatic leadership. Germany and Japan identified each other as great global powers.

“Japanese intellectuals proactively reshaped Germany’s ideals for Japanese consumption of Hitler and Nazism, keeping what they liked and removing what they didn’t like,” Law said.

With the rise of Hitler and Nazism in the early 1930s, the intellectuals and commentators in Japan became advocates and supporters. Germans positioned allied Japanese as “honorary Aryans” to establish a level of acceptance.

Law describes the German-Japanese alliance as an ideological and cultural partnership that could not survive from a practical standpoint and over a distance of 9,000 kilometers. Little travel or communication occurred between the two countries. In Germany, people of Japanese German descent were treated poorly; the nation’s race laws prohibited them from accessing certain benefits, such as a university education.

Law is quick to point out that transnational Nazism was not left in the past.

In today’s mass media landscape, Law notes that supremacists appropriate elements of Nazi ideology, add their own voice and are able to broadly distribute their message, similar to what the Japanese were doing the 1930s.

“One thing I want readers to take away is the enduring power and flexibility of Nazism as an ideology. It is like a virus with different strains,” Law said.

Law is an associate professor of history in the Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences. In his seventh year of teaching at CMU, he has led multiple offerings of Global History, a required course for Dietrich students.

“Transnational Nazism, Ideology and Culture in German-Japanese Relations, 1919–1936” is Law’s first book, published by Cambridge University Press.