Adult Subcortex Processes Numbers With Same Skill as Infants

By Shilo Rea

Despite major brain differences, many species from spiders to humans can recognize and differentiate relative quantities. Adult primates, however, are the only ones with a sophisticated cortical brain system, meaning that the others rely on a subcortex or its evolutionary equivalent.

Carnegie Mellon University scientists wanted to find out whether the adult human subcortex contributes to number processing at all. Published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences, their study found that the adult subcortex processes numbers at the same level as infants and perhaps other lower-order species, such as guppies and spiders.

"This study tells us a great deal about the human subcortex, most importantly that it does not appear to improve from its number abilities in infancy, while the cortex, which is more developed in humans than in any other species, does continuously develop," said Elliot Collins, a Ph.D. student in psychology within CMU’s Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences and a M.D. student in the School of Medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

Because the subcortex’s location and small size make it hard to observe in humans using imaging techniques, the researchers conducted a series of experiments using a stereoscope. The stereoscope allowed them to present two consecutive visual stimuli either sequentially to one eye at a time or sequentially to both eyes. This was crucial since signals that enter one eye remain separated in the subcortical part of the visual system.

One hundred adults made decisions about two groups of dots to the same eye or different eyes. The results showed that numerical judgments in the one eye trials were better under one key condition: when the first and second stimuli’s quantity differed greatly, such as having a ratio of 4:1 or 3:1.

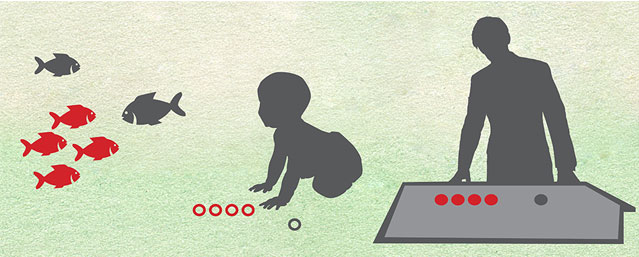

"The subcortex is not good at making fine grain number discriminations, and these findings support that," Collins said. "Our results suggest, however, that adults with a fully operational cortex still have a subcortex with the ability to distinguish number, yet it operates on a similar level to what is found in babies, other primates and lower level species who can make coarse computations of large ratios such as, for example, which shoal of fish is bigger and should be joined. This provides evidence of a potential evolutionary bridge between the human adult subcortex and the brain of lower order species."

CMU’s Marlene Behrmann, the Cowan University Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience, and the University of Massachusetts’ Joonkoo Park, who received his master’s in human-computer interaction from CMU, also participated in the study.

Grants from the National Science Foundation, Temporal Dynamics of Learning Center, NIH Medical Scientist Training Program and NIH Predoctoral Training supported this research.

Understanding how the subcortex processes numbers is one example of Carnegie Mellon's strengths in combining cutting-edge cognitive neuroscience with big data and analytics. The university's BrainHub initiative is designed to leverage these strengths further and focuses on how the structure and activity of the brain give rise to complex behaviors.