Private Military Organizations, Resource Concessions, and Conflict Termination

By Jeffrey Yohan Ko

Editor's note: The following is an excerpt from the author's Master's thesis

How private military organizations impact conflict duration in African civil wars

Introduction

At the onset of the war in Ukraine, media outlets reported that a mercenary operation called the Wagner Group was recruiting Russian prisoners to fight. There were many questions about the Wagner Group and why they were allowed to fight against the Ukrainian armed forces on behalf of the Russian government. Similar to their deployments in countries like Mali and Mozambique, there was a suspicion that the Russian government was ordering a private military organization (PMO) to carry out foreign-influence operations while maintaining the fiction that they were operating independently and without the consent of the Russian government. There were also assertions that members of the group were simply fighting for money and were committing war crimes. Videos on social media platforms showed Wagner Group members beating up and torturing prisoners while others laughed in the background. Multiple and very public negative impressions of the Wagner Group, did not relieve the incomplete understanding of their behavior during conflicts more generally, how they are financed, or the group’s long-term objectives.

Opportunity and Reward Structures for Private Military Organizations

One further question regarding the relationship between government and PMOs more generally, is how they get paid. For example, what are the motivations and doctrine that result in PMOs receiving a mining contract – as is reportedly the case between the Wagner Group and the Kremlin -- rather than payment directly? Moreover, mining contracts result in further calculations and actions required prior to and during the conflict itself. For example, how will the PMO extract resources from the country and transport it to a facility from which said resources can be sold or traded?

The ability of the PMO to obtain the proper equipment and personnel could be done through an existing subsidiary, or the PMO would have to find a third-party firm to handle the finer details of the process. From securing the ability to actualize the resource concession, the actual mining location needs to be identified and established. Again, a firm has several options for operationalizing this step. The PMO could utilize existing mining sites to fulfill the agreed upon contract. The PMO could also have stipulations that allow them to take over any mine that is recaptured from the enemy. The PMO could additionally seek political leverage over the government/insurgent authority that oversees location placement to obtain favorable agreements. Lastly, the PMO would have to possess sufficient resources to commit assets to protect and monitor these locations as well as the resources extracted. With these processes, conflicts with PMOs that have been provided resource contracts open the avenue for additional actors to be involved in the conflict.

One interpretation for the role of resource concessions in conflicts is that PMOs are seeking to maintain strategic strangleholds on the client state (Musah and Fayemi 2000). As mentioned previously, the process of actualizing resource extraction requires multiple inputs from both the PMO and the client state. The PMO has a distinct set of preferences to that of the client state. If the opportunity structure is applied here, then it can be assumed that the PMO seeks to maximize profit from its resource extraction operation whereas the client may be seeking a decisive course of action that will restore their stronghold on domestic power. Even with the opportunity structure, there may still be incentive for the PMO to prologue the duration of conflict, albeit, in a sustainable manner that does not leave their assets vulnerable (Berman and Florquin 2005).

In order for the PMO to achieve maximum benefits from their concessions, the PMO should have a cohesive internal structure. The PMO may have a board of shareholders who represent the interests and preferences of the organization to the client. A competent PMO would have the military capability to demonstrate performance in conflict, a mining subsidiary/partner, and/or financial channels.

Post-Cold War PMOs that operated within African civil wars, lacked numeric strength, but were able to compensate with supreme tactical skill and experience, organization, and equipment. These PMOs had the capabilities to ensure unilateral continuance of conflict, as in, the client would not be able to achieve victory without the aid and support of PMOs. These components can permit the PMO to directly impact the duration of conflict, by establishing itself as another actor in the conflict (Cunningham 2006).

The ability of PMOs to garner political inroads and military dependencies suggests that the actual behavior of PMOs in these conflicts only partially explain the military impact they may have in the country. Because PMOs by nature are temporal (within the bounds of a contract), there is little to no evidence to suggest that they engage in post-war processes prior to the termination of conflict in which they actively participated. A critical component of the theoretical framework, therefore, is that though there is evidence to support that PMO presence may shorten the duration of conflict (factual or counterfactual), conflict termination does not necessarily suggest that the country will not observe a resumption of conflict soon after.

PMOs operate within the opportunity structure as long as they remain actors within the country, wartime or not, and may be incentivized to find ways to formalize their presence after the terms of contract conclude.

Research Design

To study how PMOs affect civil conflicts, I proposed two hypotheses to test interactions:

Hypothesis 1: The presence of a private military organization that has been awarded a resource concession contract, rather than direct payment, is likely to lengthen the duration of the conflict.

Hypothesis 2: The higher the number of reported incidents involving members of private military organizations, combined with the state’s level of fragility, the greater the possibility that the private military organization will lengthen duration of the conflict.

I employed a combination of quantitative and case study approaches to study the effect of resource concessions to PMOs on conflict termination. I utilized the Cox-Proportional Hazard model to study the effect of a specific covariate (independent variable) on the probability of an event occurring, conflict termination in this case.

Results

For model 1 -- analyzing the relationship between resource concessions and conflict termination -- the trend indicates that a conflict in which the private military organization is awarded a resource concession is less likely to terminate at a given year y.

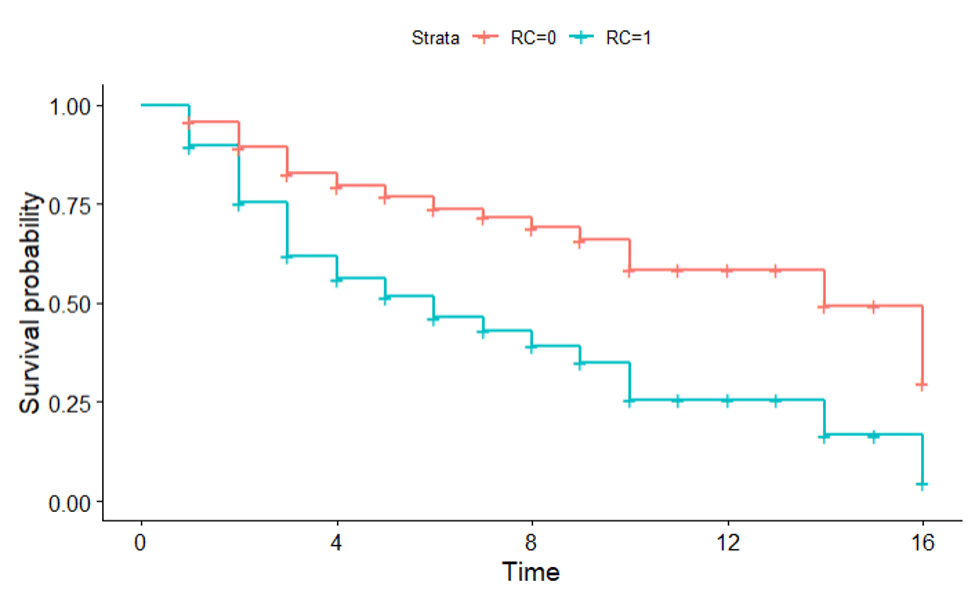

Figure 1. Relationship between resource concessions and the probability of conflict termination.

Figure 1 shows that the probability of a conflict with resource concessions awarded to the PMO, is less likely to terminate as time in years increases. The blue line represents the values observed from conflicts with PMOs that have been awarded a resource contract. The data does show some correlation between resource concessions and conflict termination, but the model itself was not statistically significant. There was a nine-percent chance that the results of the model occurred to chance probability. However, even though the model itself is not statistically significant, this model does show that, when controlled for the variables mentioned previously, there is a trend between conflict termination and resource concessions.

Case Study

Sierra Leone

Prior to the start of the civil war between the government and the RUF was categorized as a weak state lacking sufficient domestic revenue. Even prior to the PMO’s -- Executive Outcomes (EO) -- involvement in the conflict, resource mining was vital to the country’s finances. Executive Outcomes was quickly able to gain control of Sierra Leone’s diamond market by utilizing its relationship with Branch Mining, a related firm set up by Tony Buckingham and Simon Mann based in the United Kingdom (Pech 1999). The growth of their diamond operation benefited military officers and political officials as well, with some individuals utilizing these privileges to mine diamonds themselves. Based on this evidence it is clear EO had established a strategic stronghold in the military and political affairs of its client state. This also manifested into a military-political doctrine that conflicts could be won in weak states (Reno 1997). A beneficial mutual dependency formed as a result of the performance of EO on the battlefield as well as in diamond production. This led to the coup by Julius Bio in 1996, but did not impact the relationship EO had with the ruling state. EO was operating in the country to provide security and stability, with a growing dependence on both by the government.

Angola

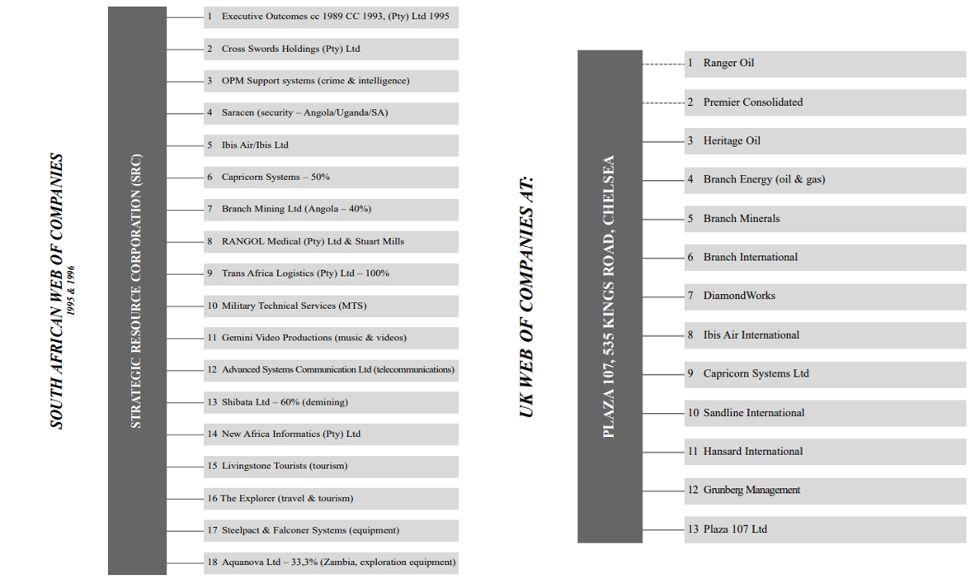

Executive Outcomes held similarly lucrative oil and diamond operations in Angola as a result of the UNITA-Angola civil war. Through Ibis Air, Executive Outcomes provided military aircraft including fighter jets, transport planes, and attack helicopters. By this point, EO had incorporated a large number of companies and operations into its parent company Strategic Resource Corporation (see Figure 2). It held controlling stakes and had major shareholders from other financial service companies, energy and metals mining companies, and private military organizations. It utilized its massive network of services to integrate itself into Angola’s economy, political system, and military forces.

Figure 2. Subsidiaries and controlling stakes of Executive Outcomes (Pech 2000)

As well equipped as EO was, UNITA were also able to buy arms and manpower. Their illicit diamond trade generated over three billion dollars from 1992 to 1998 (Sherman 2000). The vast resource wealth of UNITA created the promise of greater material benefits from fighting than trying to gain power through the political process. Executive Outcomes was able to quickly capitulate a well-armed and battle-tested opposition, while suffering several casualties. UNITA, after facing major defeats, was forced to enter peace negotiations with the ruling party in 1994.

Wagner Group

The Wagner Group targets fragile states with high levels of resource assets. The patterns visible in Sierra Leone and Angola are similar to present-day Wagner Group activity in Africa. Like Executive Outcomes, the Wagner Group posits counter-insurgency contracts and security in exchange for resource concessions, commercial ports, and other viable locations. One significant difference, however, is its indirect link to a state. Russia has been accused of utilizing groups like the Wagner Group to exert its influence abroad, while maintaining plausible deniability. Legally, employing mercenaries is outlawed in Russia, but groups like the Wagner Group have enjoyed financial backing from Russian oligarchs. Russia has also utilized port/base concessions to the Wagner Group from its client state. The Wagner Group’s demonstrative performance in the conflicts they are in do not suggest that they are engaged in the conflict to achieve victory for the client state. Rather, the Wagner Group’s footprint in unstable countries in Africa forms a satellite network of states dependent on Russian arms, training, and security.

Conclusion

Empirical approaches to the impact of private military organizations on modern civil conflicts operate on the assumption that these hired companies/groups/individuals are involved in the conflict in a way that positively impacts the course of conflict. However, I find the loose correlation between private military organization behavior and conflict termination is not well explained by the measurements we currently have. Instead, the causation element is founds only in the case study.

PMOs demonstrate engagement for the sake of asset protection, not the sake of the conflict. This doesn’t necessarily equate to shortened or lengthened duration, but rather, it makes it more difficult to finitely measure the direct impact of PMO’s behavior on conflict termination. Additionally, according to this data, indirect command and control between client and provider permits incomplete assessment of performance and behavior (Musah and Fayemi 2000). There are incentives to indicate optimal performance, but there is little to no method for clients to verify those assessments.

Resource concessions allow PMOs to shape conflicts into favorable opportunities to extract as much financial gain as possible, while supporting the political/military leaders who permit continued extraction. This differs from standing literature that arguing that resource concessions shorten conflict duration or that PMO engagement prolongs immediate conflict. Instead, the nuance of PMO behavior can be understood by demonstrating the multiple levels on which conditions for continued conflict are exacerbated. Thus, it may not be the measurable behavior that is causing conflicts to be of shorter/longer duration.