Historian Illuminates Crucial Chapter of Harriet Tubman's Legacy

Digitized Civil War pension files help researcher uncover new information about formerly enslaved ancestors

If you think you know everything about Harriet Tubman, you might be wrong.

Most will recall that she escaped enslavement and helped more than 70 others out of bondage via the Underground Railroad. However, her story is even greater than this incredible feat. Tubman also was instrumental in the success of the Combahee River Raid, the largest rebellion of enslaved people in U.S. history, which was based on intelligence she gathered as a spy for the U.S. Army Department of the South. Tubman led a group of spies, scouts and pilots who commanded Colonel James Montgomery — the regiment’s commander — the Second South Carolina Volunteers and the Third Rhode Island Heavy Artillery up the river.

Edda Fields-Black, associate professor in Carnegie Mellon University’s Department of History, spent several years researching Tubman’s role in the June 1863 event, one that freed more than 700 enslaved people during the Civil War.

“The centerpiece of Tubman’s [Civil War service] was the Combahee River Raid. In the course of six hours, she, [Union Colonel James] Montgomery and the Second South Carolina Volunteers attacked no less than seven rice plantations,” Fields-Black said. “They destroyed $6 million in property, including homes, stables, storehouses and other outbuildings, as well as millions of bushels of rice. They confiscated hundreds of heads of livestock, including 80 or 90 horses. Most of all, they set in motion the freedom of 756 enslaved people, Confederate planters’ most valuable ‘possessions.’ They did not lose a single life. One could argue that they executed the largest and most successful slave rebellion in U.S. history.”

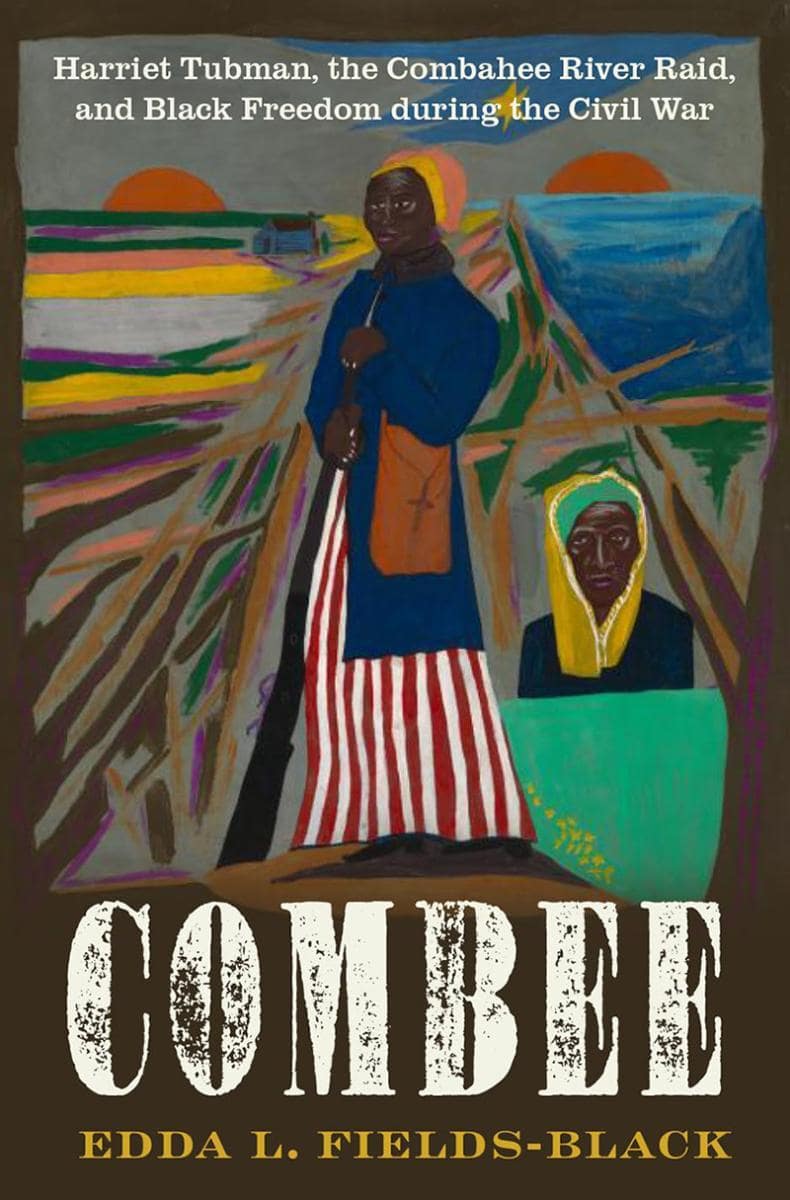

Fields-Black compiled her findings into a new book, “COMBEE: Harriet Tubman, the Combahee River Raid and the Black Freedom during the Civil War” (Oxford University Press, February 2024). The book recounts the story of the raid from the perspectives of Harriet Tubman and the previously enslaved people who liberated themselves in the raid.

“I want readers to see the humanity of the enslaved,” Fields-Black said. “I want people to see enslaved people as mothers and fathers, husbands and wives, siblings, aunties, uncles, cousins, lovers, family members who went through so much of what individuals and families go through.”

During the Civil War, the governor of Massachusetts sent Tubman to gather intelligence for the U.S. Army Department of the South. Throughout the planning and execution of the raid, Tubman and 300 formerly enslaved Black soldiers risked their own freedom to help others secure it.

“I want people to re-think freedom and the sacrifices that enslaved people were willing to make to be free. For many of them, enslavement was a fate worse than death,” Fields-Black said. “They would have rather died than been re-enslaved, and yet they are risking their freedom to go and rescue people who are still in bondage.”

Fields-Black emphasized that the raid occurred six months after the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect. From her standpoint, that level of sacrifice, devotion and courage is hard for many to fathom.

Rebuilding lineage

For Fields-Black, this story is personal. Her great-great-great grandfather Hector Fields was one of the 300 formerly enslaved men who enlisted in the South Carolina Volunteers, fought in the Combahee River Raid and risked his life for freedom alongside Harriet Tubman.

The raid lifted hundreds out of enslavement and brought their lives into focus through the historic record. Their lives were captured in the documents poured over by Fields-Black in her research. With the help of a genealogist, Fields-Black used census data, Freedmen’s Bank Account applications and other documentation to reconstruct family trees of Second South Carolina veterans and widows from the Combahee enslaved community. Then, she amassed documents from the plantation owners who held the veterans, widows and neighbors in bondage.

During the course of her research, Fields-Black made a personal discovery. Through the pension file of his lost brother, Jonas Fields (whom her family did not know existed), she found her great-great-great grandfather Hector. From testimony by Hector and Jonas Fields’ sister, Fields-Black was able to fill in gaps in her own family tree. She found her great-great-great-great grandparents, Hector’s siblings, and the location where most of her paternal grandfather’s family had been enslaved.

Fields-Black’s research process involved reading the freedom seekers’ pension file testimony. In their own words, formerly enslaved people told intimate details about their lives, including who their parents, siblings, spouses, children, cousins and childhood friends were; where they were born; who held them in bondage; to whom and with whom were they sold, mortgaged, or bequeathed; when, where, and by whom they were married; who visited them when their children were born; who attended the praise house (church) together; and what became of them, both during and after the war. Historians of slavery have to date been unable to access the intimate aspects of enslaved people’s lives in enslavers’ records, which deny the humanity of the enslaved.

“Each of the 83,000 African American veterans approved for Civil War pensions could have thousands of descendants. So, millions of African Americans could recover their family’s history using these recently digitized records. Importantly, I hope that the files will inspire and energize historians to create new tools and methods of recovering our ancestors’ names, voices and stories. This knowledge could have profound impacts on what Americans know about slavery and how we grapple with its legacy,” Fields-Black said.

Standing

While she was writing her book, Fields-Black was in residence at Nemours Wildlife Foundation, a nearly 10,000-acre research center composed of multiple former rice plantations in northern Beaufort County, South Carolina, that includes the basin of the Ashepoo, Combahee and Edisto Rivers. Nemours is located on the Combahee River where the raid took place.

“I saw the power of the river and the rice fields, just being there,” Fields-Black said. “When I had a question, I would talk to the scientists at the wildlife foundation over lunch. They would make some arrangements and we’d hop in the truck and go out to the river and the rice fields to find the answer to my questions and test my theories. I got to know most of the current landowners of the plantations that were destroyed by the raid. And, they gave me access to their properties whenever I requested it. So, I was on the ground where the raid took place. I hiked the rice fields in every season, every stage of the tide and the entire life cycle of all of the critters, especially the alligators; I was on the Combahee. I couldn’t have written the book without my collaboration with Nemours.”

Fields-Black will talk about her research and new book as a part of the Pittsburgh Arts and Lecture series at 6 p.m. Thursday, March 14, at the Carnegie Library Lecture Hall. Registration is free, and video of the lecture will be available online at a later date. Fields-Black also is bringing “COMBEE” home through a book launch at Nemours Wildlife Foundation at 2 p.m. Sunday, May 5. A full list of Fields-Black’s upcoming research talks are available online.