In New Book, Professor Doug Coulson Dissects Shifting Law of Racial Classification

By Daniel Hirsch

Throughout much of modern American history, to make determinations about the naturalization of immigrants, courts made legal decisions about who was considered “white.” In a new book out this month, Department of English assistant professor Doug Coulson examines this complex dynamics of immigration law and racial rhetoric.

In the first naturalization act passed by Congress in 1790, American law stated that to become a naturalized US citizen an immigrant had to prove they were a “free white person.” During Reconstruction, the law expanded to include “aliens of African nativity and persons of African descent.” Until 1952, when race was finally removed from the naturalization law, scores of would-be Americans — including natives of China, India, Japan, Armenia, and more — made various legal arguments pleading they should be categorized as white to stay in the country.

In the first naturalization act passed by Congress in 1790, American law stated that to become a naturalized US citizen an immigrant had to prove they were a “free white person.” During Reconstruction, the law expanded to include “aliens of African nativity and persons of African descent.” Until 1952, when race was finally removed from the naturalization law, scores of would-be Americans — including natives of China, India, Japan, Armenia, and more — made various legal arguments pleading they should be categorized as white to stay in the country.

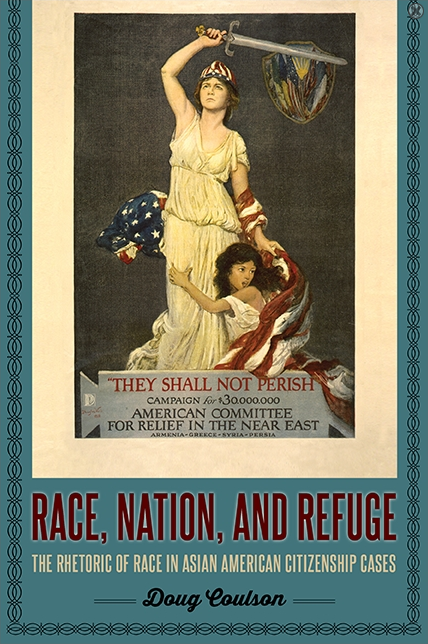

For Coulson, who studies legal rhetoric and had a previous career as a lawyer, the documents generated from these court cases became fertile ground for research into how American law understands race and the role that rhetoric plays in legal cases. As he describes in his newly published book Race, Nation, and Refuge: The Rhetoric of Race in Asian American Citizenship Cases, within the context of naturalization cases race was explicitly a political category, determined more by political and cultural criteria than skin color or biology.

“I became fascinated by how bizarre these testimonies were of people trying to, essentially, prove they’re white,” Coulson said recently. “They had to give evidence and often that evidence provided a pretty complicated picture of how this law and racial concepts were understood.”

Coulson estimates he looked at over 2000 pages of materials from the National Archives and other sources, including newspaper accounts of court cases, internal documents of the Bureau of Naturalization, US attorneys’ files, and previously unpublished court records regarding naturalization trials that occurred between Reconstruction and the early Cold War, when many laws barred the immigration and naturalization of Chinese and others from Asia and the Pacific Rim.

In his research, Coulson discovered one prevalent and especially salient theme in racial classification cases. Arguments for racial eligibility for naturalization generally— as well as the racial classification of specific immigrants — were frequently aligned with shifts in American foreign policy. The persecution of immigrants by an adversary of the United States became an effective rhetorical tool to argue for a particular racial classification.

Coulson’s books details shifting attitudes towards the Chinese as just one example. While Chinese immigrants faced a host of Chinese exclusion acts from 1882 forward due to a racialized narrative of a “Mongolian invasion,” that changed when China became an ally with the United States during World War II.

“Anti-Chinese sentiment motivated the entire body of racial naturalization cases,” Coulson said, explaining the legacy of the Chinese exclusion acts. “But during World War II when China and the United States had a shared enemy in Japan, the Chinese became like saints. Suddenly, there’s a suspension of sense of racial difference.”

With this foreign policy shift, Congress repealed the federal Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943 and Chinese persons became racially eligible for naturalized citizenship.

In a 1924 case in a United States District Court in Oregon, the legal team of an Armenian immigrant successfully argued their client was eligible for naturalization — and therefore a “free white person” — based on an argument largely centered around shared political attitudes towards Turkey. Both Armenians and Americans feared Turkish aggression and fostered similar Islamophobic attitudes.

Coulson explains that the book provides “additional evidence of what many scholars of racial theory have been saying for a long time, that race functions like any other political group formation, or that racialization can happen differently based on a variety of contextual factors.”

Race, Nation, and Refuge, which was published earlier this month by SUNY Press, emerged from Coulson’s dissertation at The University of Texas at Austin, where he first discovered the naturalization cases involving race by reading White By Law by Ian F. Haney López, the only other book length treatment of the cases.

While López almost entirely relies on published judicial opinions for his research, Coulson analyzes both the published opinions in the cases and a largely unexplored trove of archival documents and other unpublished records to fuel his rhetorical analysis. Given the vast amount of material, Coulson felt there was much more scholarship to do.

“It’s not just what judges looked at or how they decided that I was interested in, but how litigants and attorneys made arguments about racial identity,” Coulson said.

And scholarship about the rhetoric of immigration remains persistently timely. Coulson’s research has parallels in today’s political discourse about immigration law.

“Current immigration discussions often reflect a demagoguery in which speakers amplify the idea that immigrants pose a threat to the well-being of the country,” Coulson said.

For Coulson, this may explain how the rhetoric surrounding those affected by Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) has been successful by severing those affected by DACA from other immigrants by foregrounding their innocence.

“It’s interesting looking at DACA classification and how many of the activists have managed to focus the discussion on how they were these children, that they were these innocent, intransitive actors,” said Coulson. “If you can establish how they’re innocent you can ward against the status of being threatening. Those against easing immigration restrictions amplify very threatening acts and focus the discussion on that.”

Race, Nation, and Refuge is currently available for purchase through SUNY Press.

--

Above: Professor Doug Coulson in his office.