What Influences Participation During Whole-Class Discussions?

Participation decreases as pre-discussion support fades and/or reading difficulty increases. |

Reading and Writing in an Academic Context

Reading and Writing in an Academic Context is a portfolio-based, academic reading and writing course for multilingual students. The students are often international, non-native speakers of English, and represent a wide range of disciplines. Because students come from diverse backgrounds, they may be unfamiliar with certain US educational norms, such as how to participate in whole-class discussions. And, these students may need to develop interactional competence, the ability of speakers to make timely, relevant, and appropriate contributions and co-construct discussions with other speakers. In fact, Adams noticed that many of her students were not fully participating in whole-class discussions, resulting in surface-level discussions. To increase students’ participation in whole-class discussions and deepen their understanding of course texts, Adams piloted several interventions designed to teach students how to engage in whole-class discussions and develop their interactional competence.

Prior to the first whole-class discussion, Adams taught a lesson illustrating the rhetorical moves that students might use to participate productively during discussions (e.g., how to agree, disagree, ask and answer questions, comment, give an opinion, provide evidence, change the topic, etc.) and specifically stated the instructor and student roles. During the following four whole-class discussions, Adams first assigned students to small “home” groups of four students. She provided discussion questions and asked students to discuss the assigned readings for ten minutes prior to convening whole class discussion. Student groups did not change during this period (condition A), allowing students the potential to build rapport across weeks. For the next two discussions, Adams randomly assigned students to small discussion groups (condition B). This approach began to fade the social scaffolding preceding whole class discussions, without removing it entirely. For the final two discussions, rather than discuss the readings in small groups, students spent the same amount of time individually writing their answers to the discussion questions, prior to the whole class discussion (condition C). In each of the eight 25-minute whole class discussions, an observer used a protocol to record the number and type of rhetorical moves used by each student. Hereafter, total number of rhetorical moves refers to the grand total of participation events, summed across all students, per whole-class discussion.

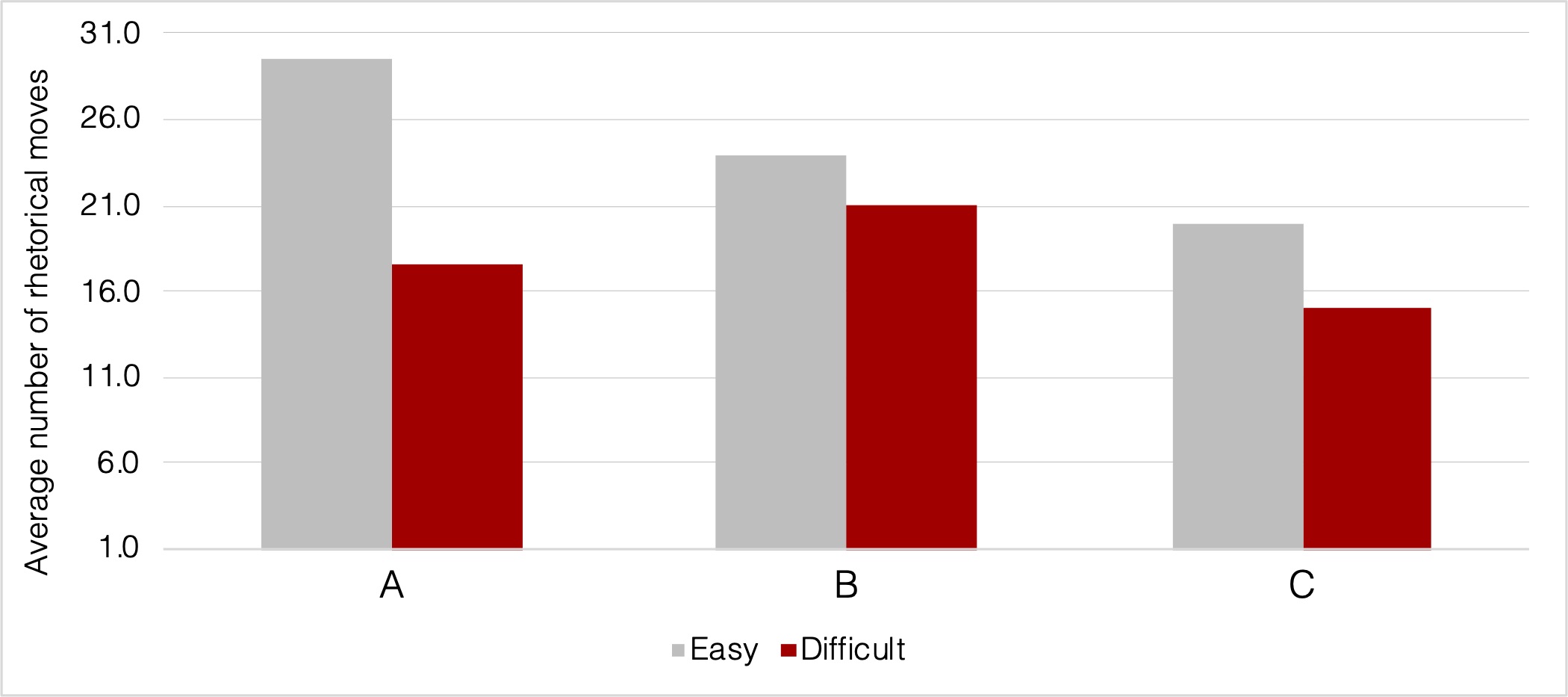

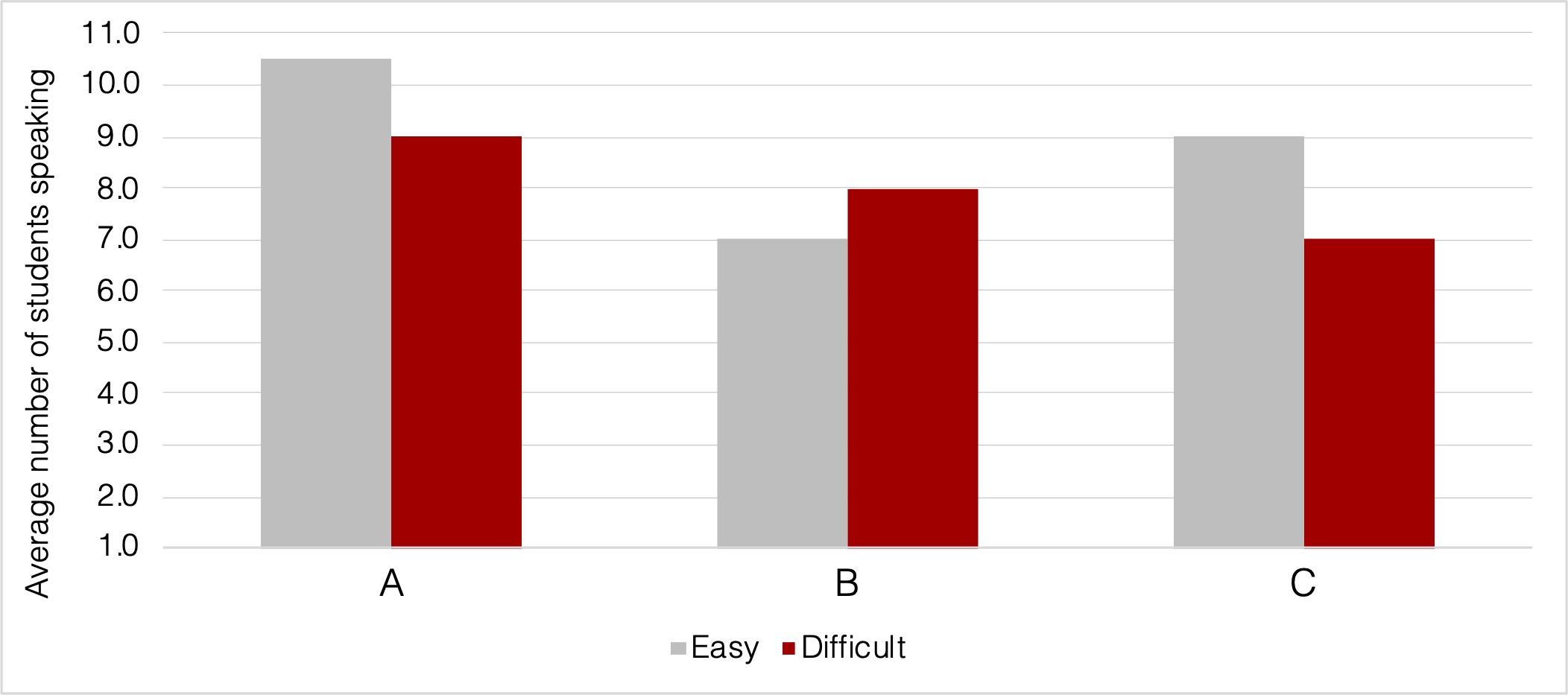

Unexpectedly, the total number of rhetorical moves decreased during whole-group discussions of difficult readings, independent of the type of pre-discussion support provided (Figure 1). The number of students participating decreased during discussion of difficult readings, compared to easy readings, and decreased as pre-discussion support changed over time (Figure 2). During discussions of difficult readings, two or three students dominated, contributing the majority of the total number of rhetorical moves observed and certain types of rhetorical moves disappeared entirely (data not shown). These trends suggest that discussions of difficult readings may have focused primarily on comprehension, rather than deeper analysis, regardless of the type of pre-discussion scaffolding. Additionally, condition C had the lowest average total number of rhetorical moves per whole-class discussion (Figure 1). Many discussion-based courses follow a similar lesson plan, i.e., asking students to discuss readings in a whole-class setting without sharing their ideas with peers in a smaller group setting first.

Overall, these preliminary results suggest that the opportunity to discuss texts in consistent small groups, before a whole-class discussion, may support interactional competence. Such small group discussions appear to encourage more students to participate as well as a larger total number of rhetorical moves during whole-class discussions. Instructors may also want to consider how assigned texts are sequenced with respect to their difficulty. Aggregating easier texts earlier in the semester may allow students the time and opportunity to practice and develop interactional competence before attempting to discuss more challenging texts. Although this study did not test it directly, explicitly teaching students why discussions are important learning activities, the implicit norms of discussion (e.g., who can participate and when, etc.), and the specific rhetorical moves needed to participate in a whole-class discussion may be equally important.

Figure 1. A rhetorical move is defined as the various ways in which students could participate in a whole-class discussion (e.g., asking or answering a question, agreeing/disagreeing, providing evidence, giving an opinion, changing the topic, etc.).

Three conditions of support were provided before whole-class discussions of assigned readings and faded across the semester: (A) consistent small groups, (B) random small groups, and (C) no small groups (n=16 students per condition).

Figure 2. The average number of students making at least one verbal contribution to the whole-class discussion per session. Three conditions of support were provided before whole-class discussions of assigned readings and faded across the semester: (A) consistent small groups, (B) random small groups, and (C) no small groups (n=16 students per condition).

Filters in which this Teaching as Research project appears:

College: Dietrich College of Humanities & Social Sciences

Course Level: Intro Undergraduate

Course Size: Small (fewer than 20 students)