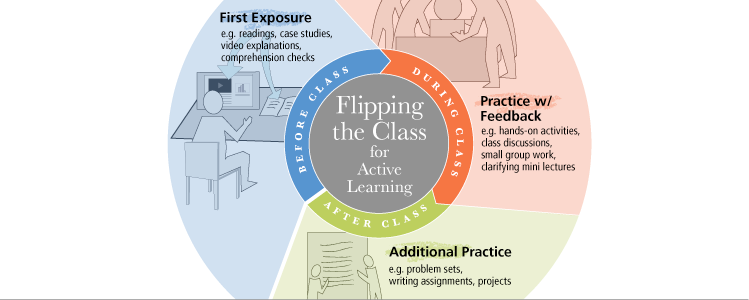

In a "Flipped Classroom," students' initial exposure to content is shifted outside of the classroom via readings, instructional videos, individual or collaborative activities, or a combination of these. Then during class, rather than lecturing, all or a significant portion of the time is used for practice, application exercises, discussion-based activities, team-based learning, or other active learning techniques. Some preliminary assessment, such as an online quiz or brief assignment, may be used to gauge student understanding and tailor instructional plans prior to class.

See what your faculty colleagues are doing!

|

|

|

|

|

"It was nice to point out to [students] that they were really able to do a lot of learning on their own, in a way that I think a lot of students don’t believe they can." |

"Why show up to class to listen to a talking book and then go home and try to apply the information on your own, when you could interact with peers and mentors to apply it during class?" |

"When you flip a course, you close the feedback loop every day. It is an amazing experience to watch your students work and to see exactly what it is they are struggling with." Charlie Garrod, Assistant Teaching Professor, Computer Science |

What are the potential benefits?

Students:

- tend to be more engaged during class, thanks to interactive activities requiring critical thinking.

- tackle more challenging “application” tasks during class – when the faculty member is present to answer questions and provide guidance – rather than when they are studying at home.

- with less prior knowledge and experience can “level the playing field” by completing pre-class work at their own pace, repeating or extending their initial learning as needed.

- receive instruction focused on what is most challenging. Advanced students are not bored by lectures on basic concepts.

- ideally, get frequent, low stakes practice and feedback during in-class activities (copious research shows this can improve learning).

- can achieve better learning outcomes when learning actively compared to passively listening to lectures (supported by research across disciplines and class sizes).

Faculty:

- spend class time focusing on challenging issues and sharing their unique perspective, rather than feeling the need to cover all the basics.

- obtain timely information (via preliminary assessments) about students’ learning before class and thereby adapt teaching plans.

- receive and respond to real-time feedback on student learning during interactive classroom activities.

- may find it more engaging and enjoyable to spend class time interacting with students, rather than giving a lecture.

Remember that all teaching strategies (e.g., flipped classroom vs. traditional lecture) have pros and cons depending on context and how they are used. One is not necessarily inherently superior to another. Effectiveness for learning ultimately depends on how strategies are implemented.

Contact us to talk with an Eberly colleague in person!

What advice do early adopters offer to faculty colleagues?

Don't flip your classroom without a good reason.

Implementation of teaching strategies is most effective when motivated by and closely aligned with your learning objectives (i.e., not just because it's possible or trendy to make instructional videos on one’s laptop).

Leave ample time to prepare.

Implementing a flipped classroom can represent a significant initial time investment, especially if pre-existing, appropriate instructional materials are not available for some topics. Leave ample time for designing instructional materials, class sessions, and pre-class work. Start small. Consider strategically flipping a few amenable topics that routinely challenge students, rather than an entire course.

Use instructional technology strategically.

There are many ways to effectively enact a flipped classroom. Many do not require technology. For example, a traditional course reading may be a sufficient foundation for pre-class work. One need not create an instructional video. However, in many cases, instructional technology may indeed help facilitate learning, student interactions, assessment of learning or instructor efficiency.

Clearly guide student preparation.

Pre-class work is most effective when students are given a clearly articulated goal or target level of performance to achieve before class and the resources to support them.

Hold students accountable.

Students are more likely to be prepared for class and participate actively if held accountable for the pre-class work.

Course materials may need to change.

One's choice of active learning strategies may require the nature of preparatory materials to change significantly. In some cases, engagement with primary sources may increase, e.g., history students analyzing and discussing historical documents and artifacts. However, in other disciplines, case-based learning may require that pre-class readings shift from exhaustive clinical reference materials to secondary distillations of key concepts, e.g., pharmacology students preparing to debate merits of different care plans in response to case studies.

Beware student overload.

How much time will students need to be prepared for class activities? Is the amount of pre-class work appropriate for the number of units/credits of the course? It is easy to add additional prep work, but you may need to make hard choices about what needs to be subtracted from your syllabus (readings, assignments, etc.) so that pre-class workload is feasible for students.

Be transparent.

Students are often initially resistant to active learning, especially if they are habituated to lecture-based courses. Clearly explain why you are teaching this way, how you think it will improve your students' learning, and your expectations for students. You need not use the term "flipping the classroom" in your explanation (some faculty experience a negative reaction to this term). You may need to revisit this multiple times or periodically highlight how particular learning experiences are designed to improve student learning beyond what’s possible in a lecture format.

"Stick to your guns."

If you are replacing lecture (or portions thereof) with active learning, and students do not come prepared to class, do not revert to lecturing. Otherwise, students will not come prepared for future classes. Lecturing briefly to clarify confusion or explain challenging concepts is fine, but avoid re-covering the basics.

Classroom infrastructure can make active learning challenging.

Furniture (e.g., long tables with chairs bolted to the floor or auditorium seating) can make active learning and small group work difficult, by inhibiting students' ability to interact or instructors' access to students, especially in rooms designed for large lectures. Plan activities knowing the constraints of your teaching environment. Students working in pairs can be effective in large classes.

Note: The above principles emerged from interviews and focus groups with faculty across disciplines who flipped their classrooms at Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Michigan.

Contact us to talk with an Eberly colleague in person!

How do I get started?

1. Identify when/where flipping could enhance learning in your course.

2. Articulate learning objectives for the portion(s) of the course you plan to flip.

3. Plan in-class activities that will help students achieve the targeted learning objective(s).

4. Identify and assign pre-class work.

5. Assign post-class activities.

Post-class assignments, activities, and projects further extend learning and promote the application and integration of course content. This is where your other (former homework) assignments and projects can come into play.

Contact us to talk with an Eberly colleague in person!

Other resources on flipped classrooms and related teaching strategies

Flipped Classroom - Simply Speaking, Penn State University (video)

A short overview of components of and selected approaches to flipped classrooms. Although this clip highlights the use of video and technology, please note that similar effective approaches without technology are effective and easily implemented.

Active Learning, University of Michigan (website)

Links to videos as well as descriptions and bibliographies for active learning strategies.

Turn to Your Neighbor: The Official Peer Instruction Blog

This blog features practical strategies and research on flipped classrooms and active learning strategies, such as peer instruction, a method leveraging discussion in pairs or small groups that is scalable to large class sizes (video example).

Team-Based Learning, University of Texas at Austin (video) and Team-Based Learning Collaborative (website)

This flipped classroom strategy use group work and includes a readiness assurance process to hold students accountable for pre-class learning and to level differences among students in preparation, and leverages team-work during class to apply learning. This strategy has been implemented effectively to replace lectures across disciplines ranging from business and history to the health professions.

Are Students Getting It?: Using Classroom Assessment Techniques to Gauge Learning and Adjust Teaching, University of Michigan (video)

How can you formatively assess student learning prior to or during a class meeting of a flipped course, with our without technology? This short video highlights simple strategies that allow instructors to modify and tailor their instruction.

Just-In-Time Teaching (website and video)

A method for leveraging online activities and assessments of learning prior to class, so that instructors may diagnose what students understand (and don’t), thereby tailoring face-to-face teaching to students needs.

Case-Based and Problem-Based Teaching, University of Michigan (website)

Links to resources on these active learning strategies emphasizing disciplinary and interdisciplinary critical thinking skills that can be the foundation of a flipped classroom course or lesson design.

Teaching Without Pants (Blog)

This blog shares lessons learned from implementing active learning and other flipped classroom strategies in a large humanities course (400 students).