What is service-learning?

What is service-learning?

Do you want students to experience working on interesting, real-world problems? Or perhaps have opportunities to apply their disciplinary knowledge in new situations where they can help others? If so, then consider how you might use service-learning – which combines traditional educational outcomes for students with “service” opportunities in the community – to meet your learning objectives. Sometimes called community-based instruction, service-learning places equal emphasis on the service component of the experience and the learning outcomes for the student. The term is generally hyphenated to indicate this balance.

Service-learning is a potentially rich educational experience, but without careful planning, students can wind up learning far less than we hope or internalizing exactly the opposite lessons we intend. For instance, if roles and expectations are not made clear, students may end up performing menial tasks, without achieving the learning goals for the course. Or they may have a bad experience and conclude, for example, that working in groups is difficult, public schools are dysfunctional, and that non-profit organizations can be chaotic places to work. In order to be successful, service-learning requires significant advance preparation and consideration of a number of special issues. But with thoughtful planning and deliberate execution, service-learning can foster positive relationships between the university and the larger community and provide meaningful educational experiences to students.

In this section, you can:

Discover what service-learning looks like at Carnegie Mellon

What does service-learning look like at Carnegie Mellon?

What does service-learning look like at Carnegie Mellon?

At Carnegie Mellon, service-learning tends to draw on the university’s traditional strengths in research and professional education: it is often project-based, built into semester-long courses, and challenges students to apply their disciplinary skills in the community. But students may also participate in a short-term assignment or in a series of projects, lasting from a few days or weeks to multiple semesters. Service-learning is similar to, yet distinct from, several other kinds of activities our students regularly engage in. For instance, volunteering for an organization may provide a similar service experience, without necessarily meeting purposeful and explicit learning outcomes. On the other hand, some courses feature partnerships with an outside organization in a “sponsored research,” “work for hire,” or “consulting” model, which may yield high student learning, but without necessarily providing a “service” to the community. In the same way, service-learning is also distinct from internships.

At Carnegie Mellon, students participating in service-learning work in Pittsburgh – and around the globe – in collaboration with community partners such as schools, arts organizations, environmental agencies, NGOs, and health and human service providers. Here are some recent examples of how our faculty have used service-learning:

In order to give students experience working with complex data and with a real client, the School of Design partners with the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Students learn about collaborating with a client to identify and scope a project by creating exciting new exhibits highlighting the research of museum staff. For example, when students realized that the museum hoped to attract more young adults, they found ways to engage twenty-something audiences with interactive displays on highly technical bird research, visually representing dense information on avian flight and environmental concerns.

In order to give students experience working with complex data and with a real client, the School of Design partners with the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Students learn about collaborating with a client to identify and scope a project by creating exciting new exhibits highlighting the research of museum staff. For example, when students realized that the museum hoped to attract more young adults, they found ways to engage twenty-something audiences with interactive displays on highly technical bird research, visually representing dense information on avian flight and environmental concerns.

In order to learn first-hand about second-language acquisition, Modern Languages sends students into the Pittsburgh Public Schools to tutor K-12 pupils. The CMU students work with language instructors as well as classroom teachers. They also complete educational projects for the schools designed to reinforce the connection between the theoretical content of the CMU course and their practical experience with second-language learners.

Students from across the university participate in technology consulting courses through the Heinz School, Computer Science, and Information Systems, learning how to articulate a community partner’s requirements and choose appropriate solution strategies. For example, a student team worked with a local dance company to identify their technology needs and designed a new membership database, using tools that the company’s small staff could maintain. A related course sends students abroad in the summer to assist organizations and government agencies in other countries with technology issues. Students learn how to write a detailed plan of action for clients with a schedule for deliverables.

Explore the learning objectives that service-learning can address

What learning objectives can service-learning address?

What learning objectives can service-learning address?

Service-learning does not automatically mean learning for the student.  But by explicitly articulating your learning objectives, and with some careful planning, many students can benefit from the opportunity to work on “messy,” authentic problems outside of the more scripted confines of a textbook or classroom context. This form of experiential learning allows students to:

But by explicitly articulating your learning objectives, and with some careful planning, many students can benefit from the opportunity to work on “messy,” authentic problems outside of the more scripted confines of a textbook or classroom context. This form of experiential learning allows students to:

- Structure an unstructured or ambiguous problem

- Integrate or synthesize knowledge and skills from previous courses

- Actively construct new knowledge

- Transfer knowledge and skills to novel situations

- Connect personal development with academic development

- Foster citizenship and leadership skills

- Develop mentoring relationships with faculty

- Learn to function within the constraints of a real institution

- Begin professional networking

Consider the appropriateness of service-learning for your course

Is service-learning appropriate for my course?

As with all instructional strategies, deciding whether service-learning is appropriate for your course depends on your objectives, resources, and constraints. Designing a service-learning course requires a great deal of up-front effort (i.e., finding and developing a relationship with a community partner) and the start-up costs can be high. Therefore, instructors may find that integrating service-learning into an entire course is more efficient than trying to fit the experience into a single assignment or unit. Also, faculty colleagues uniformly agree that teaching a service-learning course is tremendously time consuming because there is a lot of communication with students and community partners; additional checkpoints and deliverables can mean extra grading; faculty may sometimes be directly involved in the service or spend time visiting sites; and some faculty develop one-on-one mentoring relationships with students or find they need to share their personal phone numbers so they are available for problem-solving. If you don’t have the time for advance planning, or additional time to commit during the course, this may not be the semester to try service-learning.

As with all instructional strategies, deciding whether service-learning is appropriate for your course depends on your objectives, resources, and constraints. Designing a service-learning course requires a great deal of up-front effort (i.e., finding and developing a relationship with a community partner) and the start-up costs can be high. Therefore, instructors may find that integrating service-learning into an entire course is more efficient than trying to fit the experience into a single assignment or unit. Also, faculty colleagues uniformly agree that teaching a service-learning course is tremendously time consuming because there is a lot of communication with students and community partners; additional checkpoints and deliverables can mean extra grading; faculty may sometimes be directly involved in the service or spend time visiting sites; and some faculty develop one-on-one mentoring relationships with students or find they need to share their personal phone numbers so they are available for problem-solving. If you don’t have the time for advance planning, or additional time to commit during the course, this may not be the semester to try service-learning.

However, you may feel the benefits to students outweigh the planning and course management costs to you. For example, many instructors hope to convey the significance of performing community service to their students and value the kinds of authentic experiences their students have when working with a community partner. If you decide that service-learning fits with your educational vision for your course, you will need to make sure that students get out of it what you want them to. In other words, you will need to be very clear about your learning objectives and determine how you will assess student learning.

Examine issues unique to designing and teaching a service-learning course

What should I consider when designing and teaching a service-learning course?

There are a number of special considerations for instructors when designing and teaching a service-learning course. Here is some practical advice from faculty colleagues at Carnegie Mellon.

Assess student learning

Faculty sometimes believe that service-learning ought to be a “good experience” and that students will learn something – but what? With so many things going on in a typical service-learning course – such as classroom activities, on-site work with a client, independent group work, presentations, and final projects – it can be difficult to know what, or whether, students are actually learning. Therefore, it is critical to clearly identify your learning objectives and clearly articulate them to students and community partners. It can help to think in terms of what you want students to be able to do by the end of the course. Do you want them to be able to professionally interact with a client or community partner? Solve ambiguous real-world problems? Analyze the social, economic, and political factors contributing to the need for the social service agency? As you identify your learning objectives, keep in mind that these are complex skills and that students must practice and gain proficiency in many discrete component skills in order to master them. Try breaking complex skills down into concrete actions and behaviors using action verbs. For instance, perhaps you want students to be able to work with a client to articulate a problem, generate several appropriate solution strategies, and write a detailed action plan.

Faculty sometimes believe that service-learning ought to be a “good experience” and that students will learn something – but what? With so many things going on in a typical service-learning course – such as classroom activities, on-site work with a client, independent group work, presentations, and final projects – it can be difficult to know what, or whether, students are actually learning. Therefore, it is critical to clearly identify your learning objectives and clearly articulate them to students and community partners. It can help to think in terms of what you want students to be able to do by the end of the course. Do you want them to be able to professionally interact with a client or community partner? Solve ambiguous real-world problems? Analyze the social, economic, and political factors contributing to the need for the social service agency? As you identify your learning objectives, keep in mind that these are complex skills and that students must practice and gain proficiency in many discrete component skills in order to master them. Try breaking complex skills down into concrete actions and behaviors using action verbs. For instance, perhaps you want students to be able to work with a client to articulate a problem, generate several appropriate solution strategies, and write a detailed action plan.

A fabulous service contribution can also distract from assessing what a student has learned. In order to assess student learning, rather than focusing exclusively on their service, faculty need to prioritize what they value in student work, then articulate learning objectives and ensure they are measurable. For example, to measure students’ ability to “identify a client’s requirements” and “write a detailed action plan,” you might ask them to submit written proposals detailing these things. A rubric for this type of assignment can help make your expectations clear and serve as an efficient scoring tool.

Because service-learning brings a third party into the traditional teacher-student learning relationship, you might wish to include the community partner in assessment, too. Some faculty ask community partners to complete a student evaluation form, attend critiques to provide feedback, and score students’ performance. It is important to provide detailed guidance for the community partner, explaining exactly what you wish to have them score or comment on, and to be explicit about how the partner’s assessment will be factored into students’ grades.

Because service-learning brings a third party into the traditional teacher-student learning relationship, you might wish to include the community partner in assessment, too. Some faculty ask community partners to complete a student evaluation form, attend critiques to provide feedback, and score students’ performance. It is important to provide detailed guidance for the community partner, explaining exactly what you wish to have them score or comment on, and to be explicit about how the partner’s assessment will be factored into students’ grades.

- Read more on learning objectives that are measurable for assessment purposes

- Read more on assessing learning and assessing group work

- Contact us for a one-on-one teaching consultation

- For a discussion of learning objectives in a Carnegie Mellon course, see:

Mertz, J. and S. McElfresh (2010). Teaching Communication, Leadership, and the Social context of Computing Via a Consulting Course. SIGCSE'10. Milwaukee, Wisconsin, ACM. (pdf)

Establish an appropriate relationship with a community partner

Most faculty who decide to teach a service-learning course either draw on their own professional networks to locate a suitable community partner, or have been approached by an organization seeking student help. The Gelfand Center can also help establish relationships with local schools or non-profit educational entities. The key is that both parties view the relationship as mutually beneficial and an equal partnership. For this reason, many service-learning instructors refer to “community partners” rather than course “clients” or “sponsors,” which have slightly different connotations in different disciplines. Regardless, the emphasis on reciprocity and partnership is significant, as the community organization needs to be a full collaborator in student learning.

Communicate expectations

Communicating expectations of the partnership – early, often, and precisely – is crucial to a successful course. For instance, both parties need to agree on a schedule, deliverables, location of meetings, issues of intellectual property, and whether the community partner will attend classroom sessions or final presentations to offer feedback or critiques. Many faculty put this into a formal letter of agreement or memorandum of understanding (doc). A regular system of communication during the course will help identify potential problems and prevent small issues from becoming large problems. Some instructors use a project log or student evaluation form, completed at designated intervals by the community partner, to stay in the loop. When expectations are realistic they are more easily attained and instructors, community partners, and students are more likely to express satisfaction with the service-learning experience. This can go a long way towards fostering an ongoing relationship with an organization for future courses.

Communicating expectations of the partnership – early, often, and precisely – is crucial to a successful course. For instance, both parties need to agree on a schedule, deliverables, location of meetings, issues of intellectual property, and whether the community partner will attend classroom sessions or final presentations to offer feedback or critiques. Many faculty put this into a formal letter of agreement or memorandum of understanding (doc). A regular system of communication during the course will help identify potential problems and prevent small issues from becoming large problems. Some instructors use a project log or student evaluation form, completed at designated intervals by the community partner, to stay in the loop. When expectations are realistic they are more easily attained and instructors, community partners, and students are more likely to express satisfaction with the service-learning experience. This can go a long way towards fostering an ongoing relationship with an organization for future courses.

Choose classroom activities that support the service

Most service-learning courses combine traditional classroom activities with time on-site working with the community partner. For instance, you might use selected readings to focus students on big themes in the course and class discussion to help them connect those themes to their experiences working with the community partner. You might also structure class time for group presentations and feedback.

Research shows that the key to students linking their learning to their service experience is reflection: students need to reflect on their experience in a structured way. But if reflection is too open-ended or vague, it is likely to be unhelpful: for example, simply asking students to post their thoughts and feelings to a blog may produce nothing more than a disconnected list of impressions and complaints. However, you might use a blog format requiring students to respond to pointed questions that tie into your learning objectives. For instance, you might ask students to explain one thing they discovered this week while working with the community partner that connects theory to practice and how it fits in the context of the course readings.

Reflective assignments can call for the student to think deeply and critically about specific issues (e.g., the implications of particular policies for local environmental activists, legal problems encountered in needle exchange programs) or to reflect on what they’ve learned about themselves from the service-learning experience. Some faculty have students reflect on their work at the end of the course, in final submissions or a special project. Others use journaling as a reflection tool, having students write weekly pieces connecting their classroom learning with what they are doing with the community partner. You might also have students compile a course portfolio, including evidence that they accomplished each learning objective.

Reflective assignments can call for the student to think deeply and critically about specific issues (e.g., the implications of particular policies for local environmental activists, legal problems encountered in needle exchange programs) or to reflect on what they’ve learned about themselves from the service-learning experience. Some faculty have students reflect on their work at the end of the course, in final submissions or a special project. Others use journaling as a reflection tool, having students write weekly pieces connecting their classroom learning with what they are doing with the community partner. You might also have students compile a course portfolio, including evidence that they accomplished each learning objective.

- Read more on choosing appropriate learning strategies

- For an example of reflection in a Carnegie Mellon course, see:

Polansky, S. and et.al. (2010). "Tales of Tutors: The Role of Narrative in Language Learning and Service-Learning." Foreign Language Annals 43(2): 304-323. (pdf)

Consider nuts and bolts issues

Consider nuts and bolts issues

Student selection: While some service-learning courses are open to any interested student, or even required of all students in a program, some instructors establish pre-requisites or even screen students through applications before enrolling them. This requires advance planning, as students need time to gather necessary application materials, including references if requested, the semester before the course begins.

Travel and transportation: If the students will be working on-site for the community partner, how will they get there? Is there parking? How far away is the site and will travel time significantly cut into students’ available time for the course? When assigning students to groups, some faculty make sure each group has access to a car. The Gelfand Center owns a van that instructors can request for transportation if students are working on K-12 education projects. There is a small fee for the use of the van, to help offset costs.

Prerequisites: If your students will be working with certain populations, such as public school pupils or the incarcerated, they will need to have criminal or child abuse background checks conducted through the state. The Gelfand Center can assist students in getting their clearances, but you should remember that it can take several weeks for these to come through and plan accordingly. Other prerequisites might include FBI fingerprinting or tuberculosis testing. The Gelfand Center will cover the fees for criminal and child abuse clearances for students who will work with children.

Partner schedule: Determine the start and end dates for the community service. Make sure you consider both the university official calendar and the community partner’s schedule.

View a timeline for planning the logistics of your course

What is the timeline for planning the logistics of a service-learning course?

Below is a rough timeline of things to consider when planning a service-learning course. The precise timing depends on whether the course is new or has been offered before, how much time you have to prepare, departmental differences, and individual preference. Although this timeline is not exhaustive or relevant to every course, it is a general guide for those teaching service-learning courses.

Long term:

- Determine the broad goals of your course

- Decide how service-learning will fit in the course (one assignment? entire course?)

- Locate a community partner

- Screen potential students and check references (if course is “by permission of instructor”)

- Find out if students will need criminal background checks, fingerprinting, or other testing (e.g., tuberculosis) and start that process; contact Gelfand Center for assistance

Middle term:

- Articulate learning objectives for your course

- Identify appropriate classroom strategies to support the service-learning, such as readings or lectures

- Choose appropriate reflection exercises

- Ensure the alignment of objectives, assessments, and instructional strategies

- Write a tentative syllabus

- Develop appropriate forms for working with community partner (needs assessment, student evaluations, final evaluation)

- Meet with community partner to discuss issues of scale, scope, final product, and any requirements (such as attendance at presentations)

- Coordinate schedule for semester with partner

- Consider issues of intellectual property

- Draft memorandum of understanding

- Work out travel and transportation arrangements; possibly request van from the Gelfand Center

Short term:

- Formalize agreement with community partner

- Finalize plans with partner (deliverables, schedule, location of meetings, expectations for evaluation)

Identify common pitfalls as well as possible strategies

What are some common pitfalls and possible strategies?

Some Carnegie Mellon faculty have been teaching service-learning courses for many years and have shared some of the common pitfalls they have discovered as well as possible strategies to address those challenges.

| Pitfall | Possible Strategies |

| Faculty underestimate time commitment on their part | Consider whether service-learning is appropriate for your course given the time you have to plan and teach the course. Consider scaling back the course – for instance, work with one community partner rather than multiple agencies if building appropriate relationships is too time-consuming. Don’t try service-learning if you can’t reconcile the time investment required with the potential pay-off for the course. |

| Community partner has unrealistic expectations | Use early, frequent, and precise communication with community partner. Write a formal memorandum of understanding (pdf). Make expectations for any final product clear from beginning. Build in multiple feedback points to catch problems early. |

| Community partner struggles to define its needs | Communicate with community partners in advance, and if possible, narrow the range of potential problems students will help them address. Ensure that students will have a consistent contact person at the organization with whom they will work. Help students develop appropriate communication skills, such as a set of questions to use when working with the community partner. Consider building a needs assessment into the course requirements. |

| Community partner changes mind mid-semester | Involve partners in assessing an early deliverable so they are on board with the project. Work with students to see change as part of real-world problem solving. Develop contingency plans such as having students complete a project with you as the client. |

| Community partner becomes disengaged | If students do not deliver agreed upon products or fall behind schedule, community organizations can become frustrated and disengage with a project. Figure out why students are struggling and address possible issues of motivation. Partners can also experience unanticipated complications such as staffing changes that cause them to pull back from a project. Use regular communication to stay on top of changing conditions at the community organization or with student participants. |

| Community partner is disappointed with final product | Use communication and early and frequent deliverables so all parties are in agreement on where the project is headed. Have students write a formal proposal detailing scale, scope, and content of final work and get partner sign-off. Debrief with the partner to understand how the process went, sources of any disappointment, and what could be done differently next time. |

| Students think they know what is best for community partner | Work with students in advance to help them understand that the community partner must define its own needs, that the partner has something to teach them, and that they need to approach the project with humility. Practice skills they will need, such as observation and active listening. |

| Students struggle with scale and scope of project | Work with community partners in advance to limit scope. Have students submit an early deliverable (possibly just a few weeks into the semester) to address issues of scale. |

| Students lose motivation | Be explicit up front about time commitment, nature of the work, and why it is valuable in terms of students’ intellectual development, professional growth, etc. Have weekly deadlines or deliverables to keep the project on students’ priority list. Consider screening students or using pre-requisites to select appropriately motivated participants. Work with partners in advance to ensure problems are of appropriate scale, scope, and nature to maintain student interest. |

| Students act unprofessionally | As this could be a student’s first real-world experience, be clear about expectations of professional behavior, dress, and attendance. Coach students on specifics such as the appropriate way to cancel appointments. Unprofessional behavior can also be a sign of low motivation (see above) and poor group dynamics (see below). |

| Students have trouble working in groups | Group work adds an additional level of complexity to any course and can be extremely difficult to manage: students often struggle in group settings because they lack the necessary teamwork skills or have personality issues, but the project itself can also undermine group functioning if it is not well-designed. Clarify your expectations about process (versus product). Provide models. Consider building interdependence into the assignment. Hold individuals accountable. Assign groups based on skills such as leadership and technical expertise and well as assets such as access to a car. Provide groups with a collaborative space if possible. [Read more on group projects that aren’t working.] |

| Students don’t make connection to classroom material | Make the connection explicit when presenting classroom material. Build in reflection exercises that force students to integrate or synthesize their readings, experiences, lectures, etc., such as journal pieces, web postings, discussion, or a final project. Make sure class material supports learning objectives. |

| Students don’t know how to approach ambiguous “real world” problems | Because this may be some students’ first experience with open-ended, non-textbook problems outside a course, you may need to give them practice with the skill of choosing an appropriate approach. Have students focus early-on on problem planning rather than the solution. Provide models. Make connections to knowledge they already have. Reassure students that discomfort is normal under conditions of uncertainty and that they will be okay. [Read more on students who can’t apply what they’ve learned.] |

| Students aren’t meeting learning objectives | Be explicit about learning objectives with students and community partner. Make sure classroom activities support your learning objectives and that students have the chance to learn and practice what you want them to be able to do by the end of the course. Consider adding instructional activities that give students a chance to use the knowledge they will need, or practice integrating multiple pieces of knowledge or skills. |

| Students are disappointed with the experience or final product | Clearly articulate your expectations for the experience or for the scale, scope, and type of final product to help students formulate their own, realistic, expectations (for instance, perhaps not all final prototypes will be fully functional). Help students understand that dealing with a failed or disappointing final product is important real-world experience. Debrief with students to learn how failure occurred and what could be done differently next time. |

Locate Resources, Examples, and References

Resources for Service-Learning Instructors:

| For help with… | See… |

| Designing and teaching a service-learning course | Design and Teach a Course Contact Eberly for individual consultations |

| Getting inspired by existing service-learning courses | |

| Transporting students to community partners | Gelfand Center, transportation request form |

| Applying for criminal and child abuse clearances | Gelfand Center |

| Clarifying intellectual property issues or creating an official memorandum of understanding | Office of Sponsored Programs |

Service-Learning Examples from Carnegie Mellon Faculty

Tutoring for Community Outreach (82-281, Modern Languages)

Instructor: Dr. Susan Polansky

Site includes: course syllabus, sample letter of introduction to community partner, sample request for feedback, community partner evaluation sheet, guidelines for final project

Information Systems Applications (88-275, Information Systems)

Instructor: Dr. Randy Weinberg

Technology Consulting in the Community (Heinz School and Computer Science)

Instructor: Dr. Joe Mertz

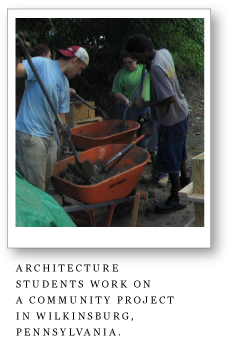

Urban Design Build Studio (48-500, Architecture)

Instructor: John Folan

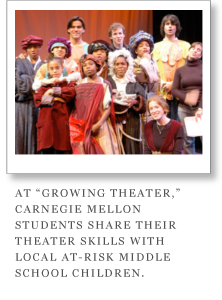

Growing Theatre Community Outreach (54-483/390, Drama)

Instructor: Anne Mundell

References, research, toolkits:

- Campus Compact. (2010). Strategies for Creating an Engaged Campus: An Advanced Service Learning Toolkit for Academic Leaders.

- Eyler, J., & D.E. Giles, Jr. (1999). Where's the Learning in Service-Learning? San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Howard, J. (2001). "Principles of Good Practice for Service-Learning Pedagogy." Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning 8: 16-19.

- Jacoby, B., ed. (1996). Service-Learning in Higher Education: Concepts and Practices. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Engelwood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Mertz, J., & S. McElfresh (2010). Teaching Communication, Leadership, and the Social Context of Computing via a Consulting Course. SIGCSE'10. Milwaukee, Wisconsin, ACM.

- Payne, D.A. (2000). Evaluating Service-Learning Activities and Programs. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, Inc.

- Polansky, S. (2004). "Tutoring for Community Outreach: A Course Model for Language Learning and Bridge Building Between Universities and Public Schools." Foreign Language Annals 37(3): 367-373.

- Polansky, S., Andrianoff, T., Bernard, J.B., Flores, A., Gardocki, I.A., Handerhan, R.J., Park, J., & L. Young. (2010). "Tales of Tutors: The Role of Narrative in Language Learning and Service-Learning." Foreign Language Annals 43(2): 304-323.

- Seifer, S.D., & K. Connors, eds. (2007). Faculty Toolkit for Service-Learning in Higher Education. Scotts Valley, CA: Learn and Serve America's National Service-Learning Clearinghouse.