Anti-Racist Pedagogy

Instructors may be interested in being actively anti-racist, but unsure of how to get started. In this introductory guide to anti-racism in higher education, we have compiled examples of principles and research-based strategies.

Anti-racist pedagogy is a holistic approach that goes beyond implementing inclusive teaching methods to tackle the structures that produce and reproduce racial inequalities. An anti-racist pedagogical approach creates numerous opportunities to better serve all students and the larger community.

If you have questions about anti-racist pedagogy and how we can support your CMU teaching, please contact us, eberly-assist@andrew.cmu.edu

What is anti-racist pedagogy?

Anti-racist pedagogy (ARP) is a part of the process of fighting racism. Despite the common assumption that “pedagogy” refers only to what an instructor does in the classroom, “anti-racist pedagogy is an organizing effort for institutional and social change that is much broader than teaching in the classroom” (Kishimoto, 2018, p. 540). Anti-racism locates the roots of problems in power and policies rather than groups of people or individuals, advocates for racial equality, and confronts inequalities rather than allowing them to continue unchallenged (Kendi, 2019). It begins by recognizing and speaking out against the ways that individuals, teaching practices, curricula, policies, and institutions can contribute to racism.

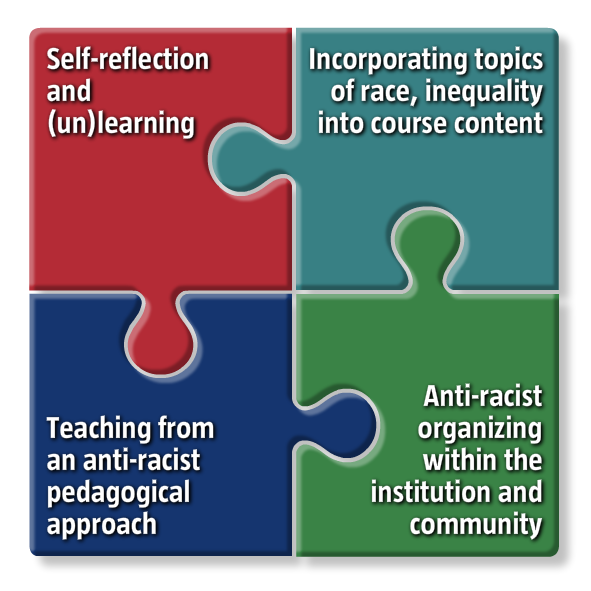

As an instructor, what can you do? Drawing on the work of Dr. Kyoko Kishimoto (2018) and other scholars (e.g., Alderman et al., 2021), we identify four major areas of action. Regardless of discipline, you can engage in a process of self-reflection about your own social position; incorporate critical analysis of race, power, and oppression into your course content; adopt anti-racist teaching methods; and organize for racial justice inside and/or outside institutions of higher learning.

These areas of action represent a broad set of opportunities, not a list of requirements. Any of these areas can be an entry point into anti-racist work and can build on each other, and all are ongoing processes. The ultimate goal of anti-racist work is to create large-scale, structural social change (Kishimoto, 2018; Alderman et al., 2021; Kendi, 2019). In the short term on the way towards that goal, anti-racist pedagogical practices have been found to improve student persistence and retention, especially in underrepresented minority students, and to reduce inequalities in educational outcomes (reviewed in El-Amin et al., 2017 and Cronin et al., 2021).

A note on terminology: We use the term “anti-racist pedagogy” instead of “anti-racist teaching” to highlight that this work goes beyond instruction in the classroom. Although we use this single term for clarity, we do not want to obscure all of the work done for many decades under overlapping terms: “critical pedagogy,” “culturally responsive” and “culturally sustaining pedagogy,” “asset pedagogies,” “teaching for liberation,” “abolitionist teaching,” and more. Dr. Deonna Smith (2022) provides an excellent literature review of these strands of thought in Chapter 2 of “From Allies to Abolitionists.”

|

“Anti-racist pedagogy is not a ready-made product that professors can simply apply to their courses, but rather is a process that begins with faculty as individuals, and continues as they apply the anti-racist analysis into the course content, pedagogy, and their activities and interactions beyond the classroom” (Kishimoto, 2018, p. 543). |

How is ARP different from DEI?

|

"While diversity and inclusion initiatives seek to increase representation of BIPOC and other marginalized groups, anti-racism initiatives seek to stimulate advocacy and direct action for organizational, social, economic and political changes at scales from the individual to the institution and society.” (Cronin et al., 2021) |

Before we explore these ARP principles more deeply, it may be useful to differentiate between anti-racist pedagogy and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). DEI and its related counterparts—belonging, culture or climate, and inclusive teaching—is a broad umbrella term covering many different strategies that are designed to support marginalized groups while also benefiting everyone. Because of this breadth, instructors can incorporate DEI strategies into their courses and teaching in a variety of ways and with differing levels of engagement and commitment. In contrast, actively anti-racist pedagogies differ from DEI in both scope and level of commitment. Because ARP requires personal learning, engagement, and commitment to systemic change, the strategies associated with it are often harder to implement.

Key Features of DEI |

Key Features of ARP |

|

DEI is frequently part of the discourse and is a priority at many universities and workplaces. |

ARP is much less commonly discussed or prioritized within university settings. When ARP is explicitly stated, it is usually alongside DEI. |

|

DEI practices are often seen as a new expectation and centrally supported at all institutional levels. |

ARP practices are not typically supported at the institutional level, and there may be greater risk to instructors doing this work, especially BIPOC instructors (Tuitt et al., 2018). |

|

Instructors may incorporate DEI strategies into their teaching without reflecting critically on their own social positions or committing to actions beyond their classroom. |

ARP requires both personal growth and deliberate, direct action that goes beyond the classroom. |

|

DEI classroom strategies may overlap with ARP strategies, but in themselves are not sufficient to be considered ARP. |

ARP can utilize DEI strategies in the classroom, but extends beyond them to push for systemic change. |

|

The goal of DEI (which can be difficult to articulate, given its breadth) is often inclusion of all students into existing systems. |

The goal of ARP is widespread social change to dismantle oppressive systems and create new liberatory possibilities. |

For another take on this comparison, check out the Center for Research on Learning and Teaching’s table comparing inclusive teaching with anti-racist pedagogy.

How do I begin to teach from an anti-racist pedagogical stance?

|

"Anti-racist pedagogy is not a prescribed method that can simply be applied to our teaching, nor does it end with incorporating racial content into courses.” (Kishimoto, 2018) |

ARP can be practiced in every part of our professional lives: the classroom, the lab or studio, the department, the college, and the institution. Below, we outline some ways that instructors can begin to participate more fully in ARP within the four core areas of action. Some of these strategies fall into the area of overlap between DEI and ARP, but many of them go beyond DEI to push for more systemic change. These strategies are not meant to be exhaustive, but a way to find your own entry point in anti-racist work.

Remember that “anti-racist” is not a fixed label we can earn, but instead a type of work which we may do to different degrees at different times (Kendi, 2019). As we begin to undertake this work, it can seem overwhelming. Within each of the four areas below, it may be helpful to remember this is a process: we begin by recognizing racism, which allows us to then reveal, reject, and finally replace it (Walton et al., 2019).

Readers can engage with the sources we drew upon in creating these lists, which are cited at the end of each section. CMU instructors who would like a confidential consultation about how to apply ARP practices in their classes can reach out to eberly-assist@andrew.cmu.edu.

Self-reflection and (un)learning can include…

|

"Antiracist teaching requires instructors to engage in critical reflection on their own positionality—both as individuals in a society structured by racial capitalism, and as faculty members in particular departments, within an academic discipline.” (Cole, 2023) |

- Reflecting on your individual social position within larger contexts such as your discipline, department, and institution.

- It may be helpful to consider how others experience these spaces, to discover commonalities or differences. Many people have generously shared their experiences through social media (venues such as #BlackintheIvory) or essay collections (such as Presumed Incompetent I and II).

- Challenging your ingrained assumptions about authority, objectivity, and social relationships, as these are inevitably informed by our cultural backgrounds. White instructors may find this source on white supremacy culture helpful and provocative as you reflect.

- Analyzing the patterns of who engages and who succeeds in your classroom, either independently or with the support of Eberly assessment professionals.

- Shifting from a focus on “deficits” (as measured by dominant cultural values and in comparison to a white, privileged norm) to a focus on the unique assets every person brings with them into your classroom.

- Shifting from an individual analysis to a structural analysis of how inequities are produced.

- For example, earlier on this page we said that ARP reduces “inequalities in educational outcomes,” instead of saying it reduces “achievement gaps.” This is not just semantics. A recent study showed that 1) teachers prioritize these disparities more when they are framed as inequalities than as achievement gaps, 2) this effect is stronger for people with higher racial implicit bias, and 3) exposure to the achievement gap language actually increases endorsement of explicitly racist stereotypes. How we frame these issues is important in motivating change and not entrenching racist beliefs about students’ ability.

- Interrogating the historical and modern inequalities of your field and institution. Here is one set of possible reflection prompts (modified from Brooks et al., 2022).

- What are the foundational values and priorities of the field?

- Who has been included in shaping these? Who hasn’t? Why?

- What is the context in which we’ve gathered the research that is foundational to our field?

- What are the standard practices, norms, or assumptions in our work that have been shaped by racism and colonization?

- Who has historically benefited from our work? Who has been harmed?

- Examining and expanding who you listen to and learn from.

- Getting practice naming racism and racist ideas explicitly, so that you are able to do so on the spot when you need to.

|

"Concrete, research-driven actions are critical for change, but dismantling racism [...] also requires understanding and acknowledgement of its origins and sources.” (Cronin et al., 2021) |

This work is deeply personal, and much of it will be done on your own or with trusted people in your life. As you learn and unlearn about your discipline, consider what actions you are motivated to take to improve equity.

If you have questions about anti-racist pedagogy and how we can support your CMU teaching, please contact us, eberly-assist@andrew.cmu.edu

Incorporating critical analysis of race and inequality into course content can include…

|

"One way to discuss race, racism, power, and privilege in any course is to provide political, historical, and economical context to the development of the discipline, rather than looking at knowledge as apolitical, ahistorical, and neutral.” (Kishimoto, 2018) |

- Highlighting common themes of power, oppression, and justice to foster students’ critical analytical skills.

- Helping students feel that they should and can address social inequalities created by the work in their field. This is applicable even in disciplines where the course content itself does not seem to cover issues of race and power.

- For example, Hwang et al. (2023) offer a framework for developing a sense of social responsibility in undergraduate engineering students.

- Focusing on knowledge as constructed by human beings, and discussing both the strengths and limitations of how knowledge has historically been constructed in your field.

- For example, you might begin an introductory science course with a conversation about the scientific method as one of many different ways of making knowledge that students might bring with them or be able to learn from (Kimmerer, 2013).

- You can also teach students to analyze the language used to describe and categorize: where did it come from? who uses it? what does it do? what does it hide?

- Researching and revealing the history of who has made knowledge in your discipline and what that knowledge has been used for.

- For example, if you’re teaching about population genetics or evolution, you could also include the context of how 20th-century eugenicists in these fields developed bodies of “evidence” around racist, ableist ideas which were then used to support state policies such as forced sterilization.

- Look for, or create, an open-access list of examples how racism has shaped discipline to aid in others acknowledging this history in their own teaching. As two useful starting points, Dr. Edwin Mayorga (n.d.) has collected many topic-specific lists of resources, and Dr. Judith Lin (2023) has reviewed the contributions of race-conscious research to fields including computer science and business.

- Incorporating diverse sources (e.g., TED Talks, podcasts, YouTube videos) that represent a variety of voices and bring to light perspectives and knowledge that are obscured in American and European professionally published materials. Here are some examples of how to do this, collected from CMU instructors.

- Add to, or create, an open-access collection of other content sources created by BIPOC authors so that you and others can uplift their voices into your course content. For example, there is a growing collection of BIPOC-authored sources in the discipline of Psychology.

- Inviting students to make connections to their own experiences, find their own voices, and critically reflect on their own thinking.

CMU instructors who would like to schedule a confidential consultation can reach out to eberly-assist@andrew.cmu.edu.

Anti-racist pedagogical approaches can include…

|

"When it comes to anti-racist pedagogy, how we teach is as much or more important than what we teach.” (Cole, 2023) |

- Creating a student-centered classroom environment in which students’ interests and needs are prioritized. Student-centered pedagogy has roots in Black and feminist education movements of the past 150 years.

- This can include co-creating classroom norms, rubrics, and syllabi with students.

- Respecting and valuing students’ differences in contribution styles and forms of knowledge.

- This will likely require that you focus on the content of students’ writing and speech rather than their grammar or formality. Rigid norms around “proper” language perpetuate racist ideas. Many university writing centers have developed guides, such as this one, for making your classroom more inclusive of students’ authentic self-expression.

- When students do need to learn a disciplinary norm in order to succeed outside of your classroom, teach this “hidden curriculum” explicitly.

- Decentering authority in the classroom and sharing power/responsibility with students. There are many ways to do this, including:

- Giving students choice and autonomy in their learning. For example, allow students choice of topics or formats for major assignments. See more examples here.

- Using alternative grading methods such as specifications grading, contract grading, or ungrading. If these forms of grading are new to you, consider trying a new grading structure in one or two aspects of your course, rather than trying to convert your entire course at once.

- At a departmental level, allowing students to self-place into different curriculum tracks rather than relying on placement exams.

- Moving away from classroom policies and technologies focused on surveilling, policing, and punishing students. There is a rapidly growing body of work on restorative justice approaches to plagiarism; see the resources collected by the MSU Denver Writing Center (under the heading “Restorative Justice Approaches to Plagiarism”). Again, we are recognizing, revealing, rejecting, and replacing systems of power in classroom spaces.

- Being transparent about your expectations of students, why you have those expectations, and how students can meet them.

- Creating an inclusive classroom climate. Creating a learning space where students feel welcome, supported, and encouraged to contribute can increase student motivation and belonging.

- Implementing equity-based pedagogical modifications in course design. These modifications promote learning for all students, but have been shown to be particularly beneficial for minoritized students:

- Dedicating significant amounts of class time to active learning.

- Increasing accessibility by following the principles of Universal Design for Learning.

- Supporting students’ growth mindset, and affirming that they can meet your high expectations of them.

- Using targeted interventions such as values affirmation activities.

|

"Education either functions as an instrument that is used to facilitate the integration of the younger generation into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity to it, or it becomes ‘the practice of freedom,’ the means by which [people] deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world.” (Freire, 1970/2000, foreword by Shaull) |

If you have questions about anti-racist pedagogy and how we can support your CMU teaching, please contact us, eberly-assist@andrew.cmu.edu

Anti-racist organizing within the institution and community can include…

|

"While historically the teaching profession has often upheld the status quo, black teachers nevertheless engaged in “intellectual activism,” teaching ideals of “freedom, justice, and democracy, which have stirred younger generations of students to action.” Martin Luther King Jr. himself advocated for teachers to become activists.” - Derrick P. Alridge (2020), quoting the work of Tondra Loder-Jackson (2015) |

- Examining how students are recruited and who is retained in your major or program.

- Examining how staff and faculty are hired and promoted. This could involve new outreach efforts or expanding the criteria for evaluating performance.

- If you are in a position to do so, helping the institution establish incentives for departments to implement best practices in hiring and retention.

- Reducing reliance on student evaluations of instructors’ teaching in high-stakes decisions such as promotion and tenure. Dr. Rebecca J. Kreitzer has compiled almost 80 peer-reviewed studies showing that student evaluations are biased, many of which found bias on the basis of race and ethnicity. Dr. David Delgado Shorter (2023) has written about how this evidence can inform departmental changes.

- Consider leveraging multiple, complementary data sources (e.g., from students, peers, and yourself).

- Developing diversity vision statements, codes of conduct, and concrete actions for achieving equity at the departmental and institutional level.

- Inviting diverse speakers and establishing diverse, multi-mentor networks for all community members’ career stages to foster connection.

- Facilitating access to existing resources, such as financial planning and mental health professionals, for staff, faculty, and students.

- Advocating for thriving wages and benefits for all members of the institution, including graduate students and contract workers (often dining and cleaning staff) who are disproportionately women of color.

- Confronting the toxic normalization of overwork, which can lead to exploitation of marginalized community members.

- Examining whether policies disproportionately negatively impact people of color, and changing them.

- Making research accessible to local and impacted communities, or involving those communities in the work—for example, by decolonizing fieldwork or listening to community concerns about how surveillance technologies will be applied.

- Refusing to let research findings be appropriated to support racist ideologies or make profit through exploitation.

- Organizing against current political efforts to repress teaching about the existence of racism, such as teaching about Critical Race Theory or the history of slavery in America.

- Joining local organizations fighting for racial justice, such as those compiled by CMU’s Graduate Student Assembly.

|

"At the end of the day, White teachers need to want to address how they contribute to structural racism. They need to join the fight for education justice, racial justice, housing justice, immigration justice, food justice, queer and trans justice, labor justice, and, above all, the fight for humanity.” (Love, 2019) |

Please reach out to eberly-assist@andrew.cmu.edu with questions or to connect you to other campus resources.

What challenges might I face?

Harbin et al. (2019) and Alderman et al. (2021) identified some possible challenges for instructors teaching about race and racism, or more generally using anti-racist practices. Anti-racist pedagogy can come with vulnerability and risk, especially for instructors of color. Your experiences may vary depending on your own identities and social position. For example, a graduate student of color might face pushback from students for the same actions that a White tenured faculty member could be praised for implementing.

Students may hold simplistic or stereotyped ideas about racial identity, for instance believing race to be a biologically determined characteristic, assuming racial groups are homogenous, or rooting problems in individuals rather than systems. Racial majority students may be resistant to confronting issues of race and racism, while students of color may have internalized oppression which can complicate their participation in the course. Students within and across racial groups may have dramatically different levels of exposure to these ideas and toolkits for engaging with them. Instructors may not know how to respond productively when students respond emotionally or even challenge their authority and competency to teach.

There are other challenges that go beyond student responses. ARP takes time and energy. It can be hard to find resources and course materials to draw upon, especially if there has not yet been a concerted effort within the discipline to do the critical work of examining its part in discrimination, racism, oppression. Other members of the institution or department may also be resistant, for example if they feel that teaching should be politically “neutral.” Instructors may not know how to respond, especially if they are not familiar with evidence to prove the benefits of anti-racist practices or if they feel unsupported by their department.

Strategies to prevent negative responses

Harbin et al. (2019) and Alderman et al. (2021) also suggest ways to mitigate resistance from students. Many of these strategies have already been covered in the four categories above—for example, incorporating diverse perspectives and sources in the course content and providing multiple methods for demonstrating learning. They also offer some additional strategies we have not yet covered:

- Being proactive—anticipate students’ misconceptions about race and create course content or assignments to deconstruct these.

- Ordering course content so that students develop critical background knowledge and skills such as navigating difficult discussions before diving into challenging material.

- Engaging affective learning by encouraging emotional literacy (for example, asking students to pay attention to their embodied emotional responses during discussions of race) and developing empathy.

- Promoting reflexivity, or the ability to understand how your feelings affect your behavior. This can be done through instructor modeling or assigning reflective writing such as autobiographical essays.

- Creating a course norm of welcoming difficulty. Discomfort is an expected byproduct of grappling with racism, or even just learning new perspectives. Instructors can normalize difficulty and should immediately address any harms.

- Assessing students’ incoming knowledge and preconceptions about race. Tailor teaching methods and/or assignments to provide skills for dialogue and engage with their arguments even if they’re simplistic or flawed.

- Inviting a class to collectively make knowledge by bringing together many different perspectives and possible answers to a generative question.

- Using personal writing assignments to help empower students to relate their own stories, experiences, and knowledge.

- Cultivating a learning community and students’ sense of belonging.

- Introducing yourself and being transparent about your own identities, to the extent that feels safe and productive.

- Designing opportunities for students to learn from each other. Model humility and willingness to learn from others, for example by welcoming and incorporating student feedback.

- Finding a learning community for yourself to further your own learning.

You can build these norms by establishing guidelines for interaction early in the semester, revisiting them often, and modeling positive behaviors.

Less has been written about how to respond when colleagues and administrators respond negatively to ARP efforts. We acknowledge that this is a thorny problem without easy, one-size-fits-all solutions. Some instructors may choose to engage in this work without publicly claiming it as anti-racist, and this makes it no less valuable. Others may feel comfortable making a strong case for their departments to consider anti-racist commitments. But anyone engaged in anti-racist work can benefit from building a strong coalition of support to help prevent and respond to any challenges.

ReferencesStrategies to build coalition and community

|

"We did not realize that each of us contributed to anti-racist programming in our respective units. We now meet formally each month in the anti-racist pedagogy reflection group [...] [We have] moved towards the action stage while also growing the group.” (Stone & Cirillo-McCarthy, 2021). |

A group of peers, such as an instructor learning community or graduate student reading group, can help normalize anti-racism as an essential part of our work as educators. Such coalitions also provide encouragement and energy, which are critical when attempting a project as emotionally demanding as dismantling entrenched disciplinary and institutional racism.

Finding allies with intellectual and social capital within the institution can be critical to ensuring your freedom to speak, teach, and advocate on these topics. An ally might be a senior faculty in your department, a department head or dean, a member of your field who has written about ARP, a teaching expert who can help you find evidence that your teching methods improve student outcomes, or someone who can nominate you for a prestigious teaching award. Your coalition need not be limited to your institution, one can seek out external groups or professional organizations in higher education where you can share ideas and support one another regarding anti-racist pedagogy.

ReferencesHow can the Eberly Center support you?

The scope of anti-racist pedagogy ranges from deeply personal inner work to community activism. The Eberly Center is available to support instructors exploring anti-racist teaching methods, whether that’s creating a more equitable course design and assessments, managing classroom dynamics, incorporating technology tools to better support all students’ learning, or collecting data in the classroom. We offer group programming on these topics, confidential one-on-one consultations, and even fellowships to support major course redesigns.

Contact us to request a one-on-one meeting with an Eberly Center consultant, discuss possibilities for group programs, and/or let us know what other resources you would be interested in!

If you have questions about anti-racist pedagogy and how we can support your CMU teaching, please contact us, eberly-assist@andrew.cmu.edu

Where Can I Learn More?

Articles and books, as well as additional web resources, can be found here.