New Study Reshapes Understanding of How the Brain Recovers from Injury

Media contacts:

Abby Simmons, 412-268-6094, Carnegie Mellon University

Mark Michaud, 585-273-4790, University of Rochester Medical Center

New research, which appears in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, sheds light on how the damage in the brain caused by a stroke can lead to permanent vision impairment for approximately 265,000 Americans each year. The findings could provide researchers with a blueprint to better identify which areas of vision are recoverable, facilitating the development of more effective interventions to encourage vision recovery.

"This study breaks new ground by describing the cascade of processes that occur after a stroke in the visual center of the brain and how this ultimately leads to changes in the retina," said senior study author Brad Mahon, an associate professor at Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Rochester. "By more precisely understanding which connections between the eye and brain remain intact after a stroke, we can begin to explore therapies that encourage neuroplasticity with the ultimate goal of restoring more vision in more patients."

When a stroke occurs in the primary visual cortex, the neurons responsible for processing vision can be damaged. Depending upon the extent of the damage, this can result in blind areas in the field of vision. While some patients spontaneously recover vision over time, for most the loss is permanent. A long-known consequence of damage to neurons in this area of the brain is the progressive atrophy of cells in the eyes, called retinal ganglion cells.

READ MORE

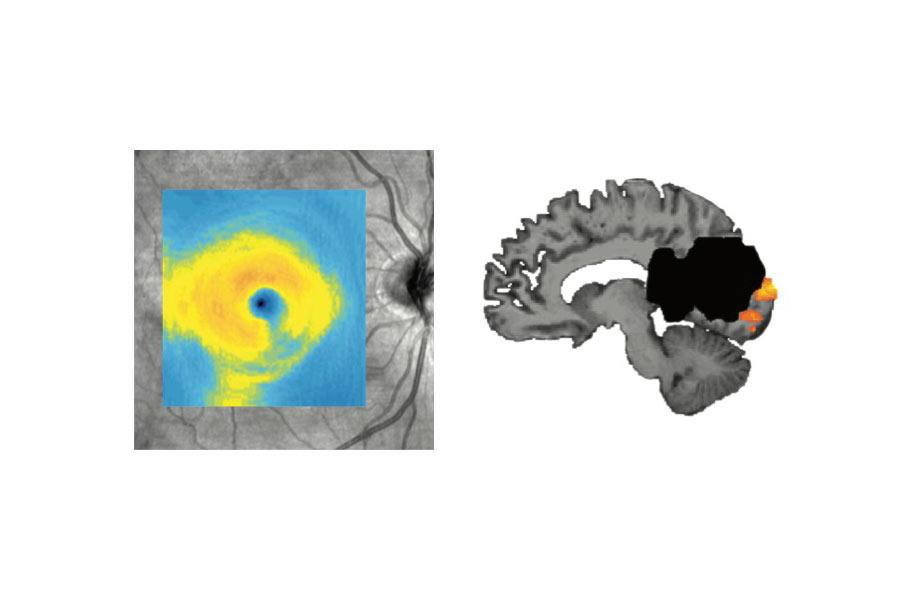

Pictured above: The left image shows degeneration that typically occurs in the eye (lower right corner) after a patient has a stroke in the visual processing area of the brain. The area of degeneration corresponds to the location of blind areas of the patient's visual field. Carnegie Mellon and University of Rochester researchers found the eye is less likely to degenerate when the brain continues to respond to visual stimuli despite the patient's blindness from the stroke. The right image shows lesion in black and visual cortex activity to stimuli presented in blind areas of the patient's visual field in orange.