In This Section

Researchers Unlock Clues to the Origin of the Longest Gamma-ray Burst Ever Observed

Carnegie Mellon study uncovers the jet launched by an actively feeding black hole

By Amy Pavlak Laird Email Amy Pavlak Laird

- Associate Dean of Marketing and Communications, MCS

- Email opdyke@andrew.cmu.edu

- Phone 412-268-9982

Astronomers have observed the longest-ever gamma-ray burst — a powerful, extragalactic explosion that lasted more than seven hours. It was so extraordinary that several teams of scientists have been poring over a flood of data from both Earth- and space-based telescopes and satellites to make sense of it. Observations from a team led by Carnegie Mellon University are providing crucial information about the possible origin of this unusual event.

While most gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) are over in a minute, this one displayed multiple bursting episodes over the course of seven hours and its afterglow lasted for months. The event, dubbed GRB 250702B, is the longest gamma-ray burst humans have ever witnessed.

“GRB 250702B is an extremely interesting event that does not neatly match any other high-energy transients that we have observed in the past 50 years,” said Brendan O'Connor, a McWilliams Postdoctoral Fellow at Carnegie Mellon’s McWilliams Center for Cosmology and Astrophysics. “There were multiple, distinct gamma-ray detections separated in time, which is very peculiar. It’s the main reason we all dedicated extensive telescope time to studying it.”

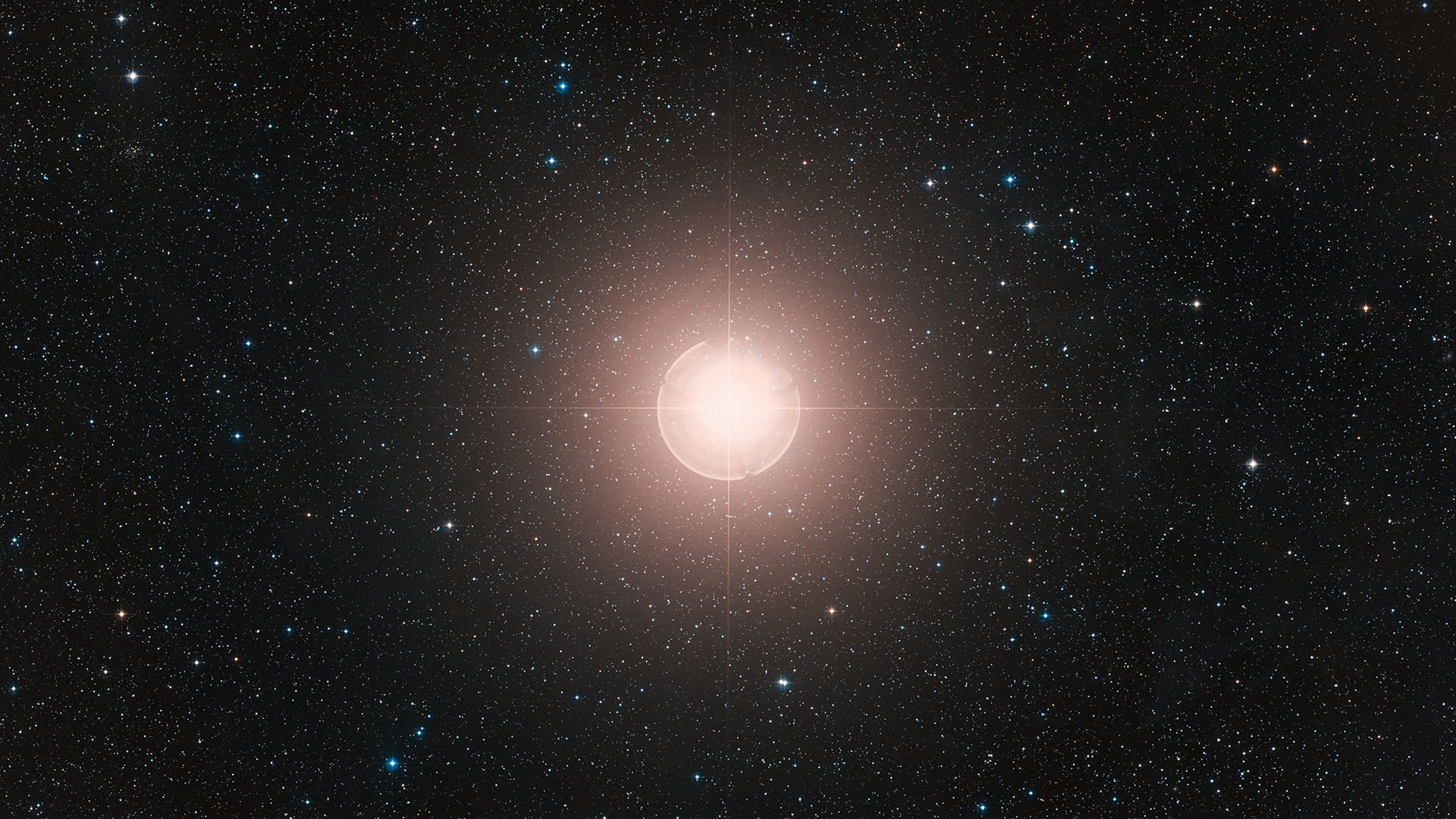

Most gamma-ray bursts last from a few milliseconds to a few minutes and are known to form in two ways, either by a merger of two city-sized neutron stars or the collapse of a massive star once its core runs out of fuel. Each produces a new black hole. Some of the matter falling toward the black hole becomes channeled into tight jets of particles that stream out at almost the speed of light, creating gamma rays as they go. But neither of these types of bursts can readily create jets able to fire for days, which is why 250702B poses a unique puzzle.

The unusual GRB was first identified by NASA’s Fermi Gamma-Ray Space Telescope on July 2. Shortly after the initial gamma-ray bursts were detected, a team led by O’Connor directed three space-based telescopes to monitor the afterglow in X-rays, which they did for 65 days. The properties of these X-rays can provide clues about the type of event that caused the GRB. Their findings were published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

O’Connor’s comprehensive study of the X-ray data gathered with the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, the Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array, and the Chandra X-ray Observatory reveal that GRB 250702B is an outlier that doesn’t quite fit with any of the explanations for the origin of other GRBs.

Scientists say the best explanation for the outburst is that a black hole consumed a star, but they disagree on exactly how it happened.

“The continued accretion of matter by the black hole powered an outflow that produced these flares, but the process continued far longer than is possible in standard GRB models,” said O’Connor. “The late X-ray flares show us that the blast’s power source refused to shut off, which means the black hole kept feeding for at least a few days after the initial eruption.”

The Carnegie Mellon team’s analysis points to a star being shredded by a stellar-mass black hole, which is on the small-side as far as black holes go. Instead of the supermassive black holes at the center of all galaxies, these smaller black holes are left behind when a massive star dies.

In this scenario, the shredded star is eaten by its companion star after becoming spaghettified by the black hole’s gravitational forces. As the black hole rapidly consumes the star’s matter, rapid jets blast outward near the speed of light, producing the initial flashes of gamma-rays and later the X-ray afterglow. Astronomers call this a jetted tidal disruption event (TDE), which is usually linked to a supermassive black hole. However, in this case, O’Connor refers to it as a micro-TDE because it involves a black hole that’s a million times smaller.

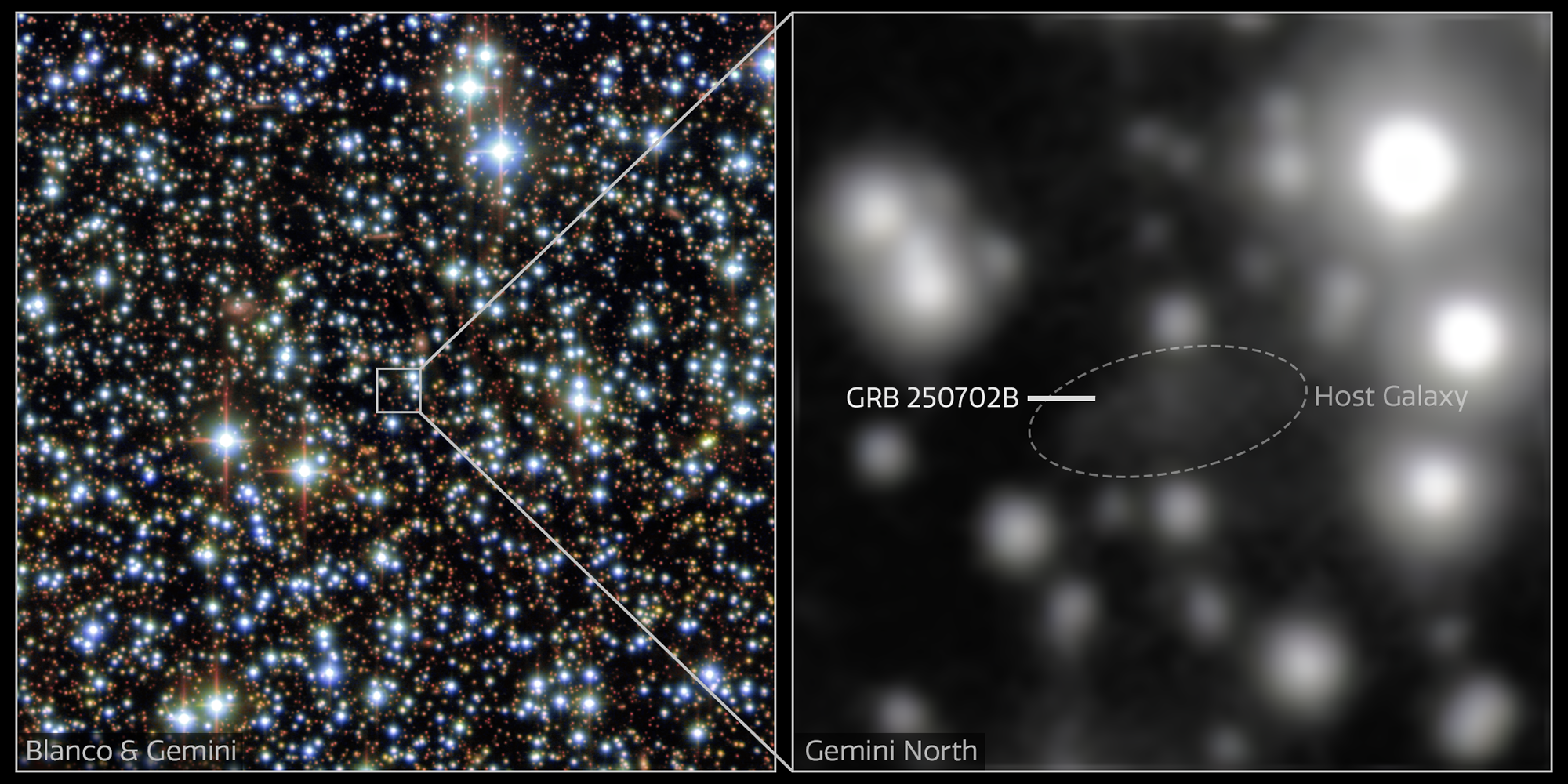

Using a variety of telescopes around the globe and in space, scientists pinpointed GRB 250702B’s location in the constellation Scutum, near the crowded, dusty plane of our Milky Way galaxy. A detailed study led by Jonathan Carney, a graduate student at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, shows that the host galaxy is very different from the typically small galaxies that host most stellar collapse GRBs. “This galaxy turns out to be surprisingly large, with more than twice the mass of our own galaxy,” he said.

O’Connor, Carnegie Mellon graduate students Hannah Skobe and Xander Hall, and Assistant Physics Professor Antonella Palmese contributed to Carney’s research.

“The studies of the host galaxy can inform the origin of this unusual transient,” Palmese said. “By looking at the morphology and stellar population, we can understand what the history of this galaxy may have been.”

Skobe led an analysis of the galaxy’s size and shape using images taken with NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. “Looking at the Hubble data, it was unclear whether the system was a merger of two separate galaxies or a single galaxy with a dust lane,” said Skobe, a third-year graduate student in the Department of Physics. “To investigate this, we modeled the data for both cases but couldn’t distinguish which was preferred.”

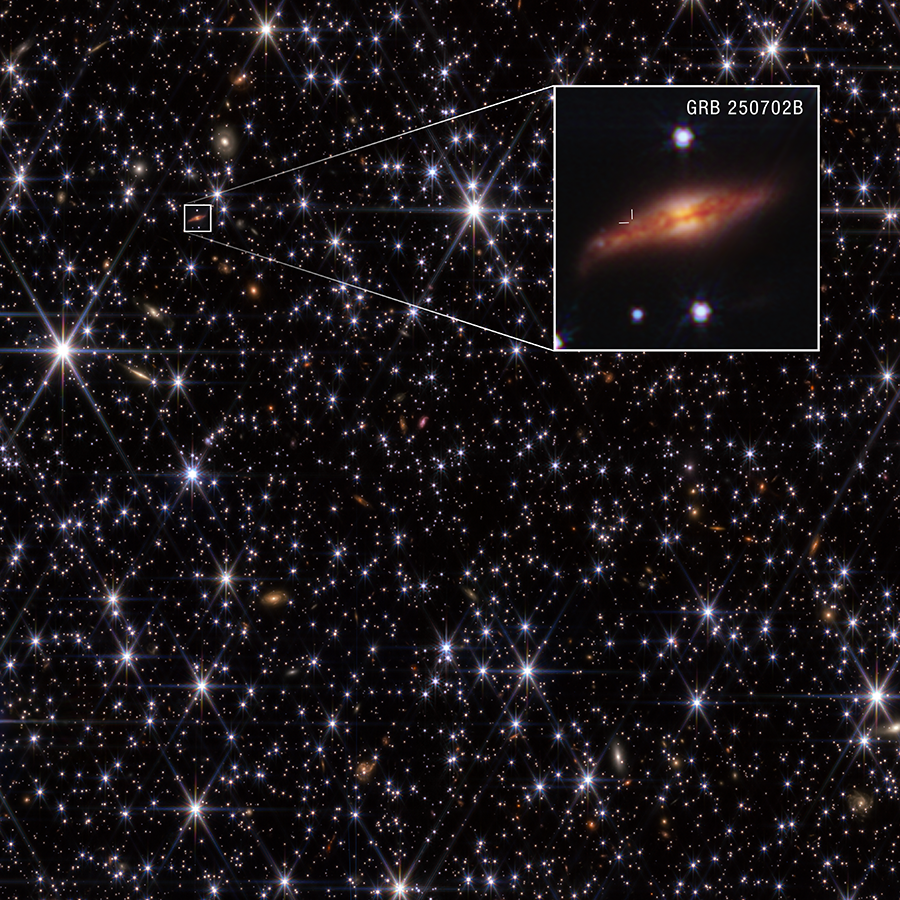

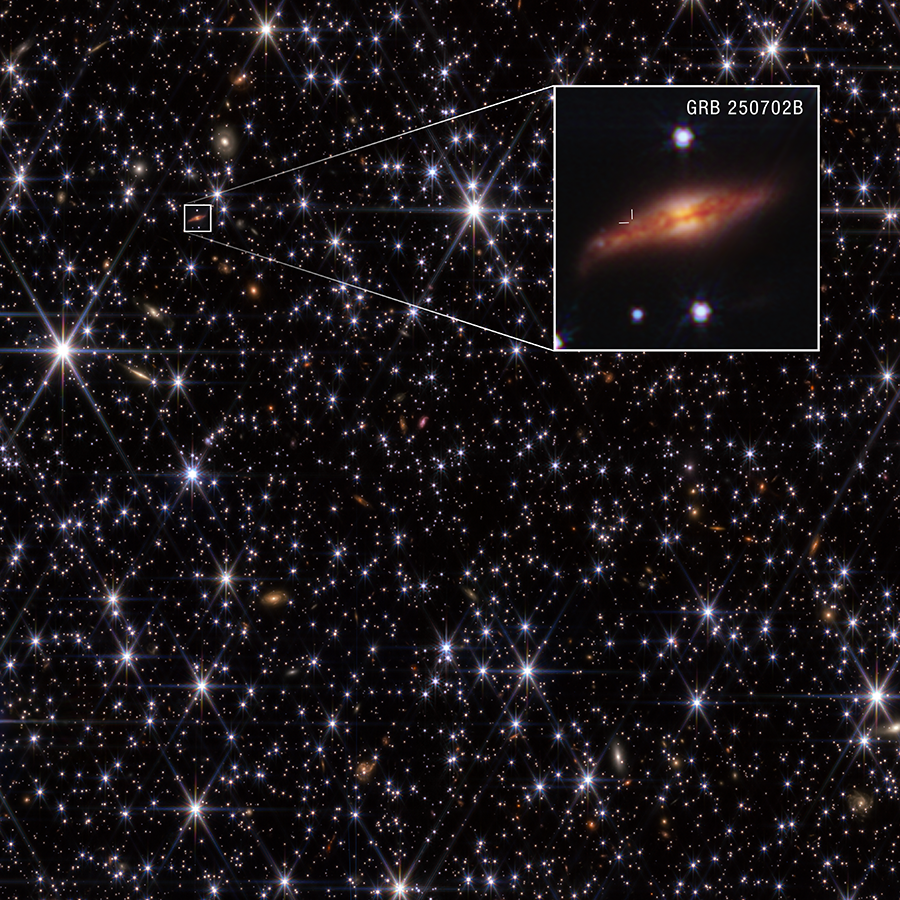

Additional imaging later taken with the NIRcam instrument on NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope proved that the galaxy was indeed split by a dust lane.

“The resolution of Webb is unbelievable. We can see so clearly that the burst shined through this dust lane spilling across the galaxy,” said Huei Sears, a postdoctoral researcher at Rutgers University who led the team that acquired the James Webb Space Telescope imaging. The team included Carnegie Mellon’s O’Connor and Hall.

In addition to the Carnegie Mellon University scientists, an international team of astronomers were involved with the work, including Ramandeep Gill (Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico and The Open University of Israel), James DeLaunay, Jamie A. Kennea and Simone Dichiara (The Pennsylvania State University), Jeremy Hare (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, The Catholic University of America), Dheeraj Pasham (Eureka Scientific, The George Washington University), Eric R. Coughlin and Ananya Bandopadhyay (Syracuse University), Akash Anumarlapudi, Igor Andreoni, Jonathan Carney and James Freeburn (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Paz Beniamini and Jonathan Granot (The Open University of Israel, The George Washington University), Michael Moss and Tyler Parsotan (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center), Ersin Göğüş (Sabancı University), Malte Busmann (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München), Daniel Gruen (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Excellence Cluster ORIGINS), Samuele Ronchini (The Pennsylvania State University, Gran Sasso Science Institute), Aaron Tohuvavohu (California Institute of Technology) and Maia A. Williams (Northwestern University).

This study uses data obtained from several sources, including: Gamma-ray Burst Monitor (GBM) on NASA’s Fermi Gamma-Ray Space Telescope (Fermi); NASA’s Chandra X-Ray Observatory; NASA’s NuSTAR (Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array) mission; the Burst Alert Telescope on NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory; James Webb Space Telescope; the Russian Konus instrument on NASA’s Wind mission; the Wide-field X-ray Telescope on China’s Einstein Probe; DECam and NEWFIRM on the NSF Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO); Gemini Multi-Object Spectrographs (GMOS-N and GMOS-S) at the International Gemini Observatory; Fraunhofer Telescope at Wendelstein Observatory; Hubble Space Telescope (HST); Keck I Telescope at the W. M. Keck Observatory; and FourStar on the Magellan Baade Telescope.