Expanding Minds

CMU alumna advocates for better science policy and communications to create a more informed future

By Amanda S.F. Hartle

As a neuroscientist, Carnegie Mellon University alumna Meredith Schmehl knows better than most the unlimited power of the human brain.

So she’s using hers to create a better future — distilling complex scientific ideas into conversations anyone can understand, empowering other scientists to become better advocates for their fields, and making STEM more accessible and all-encompassing.

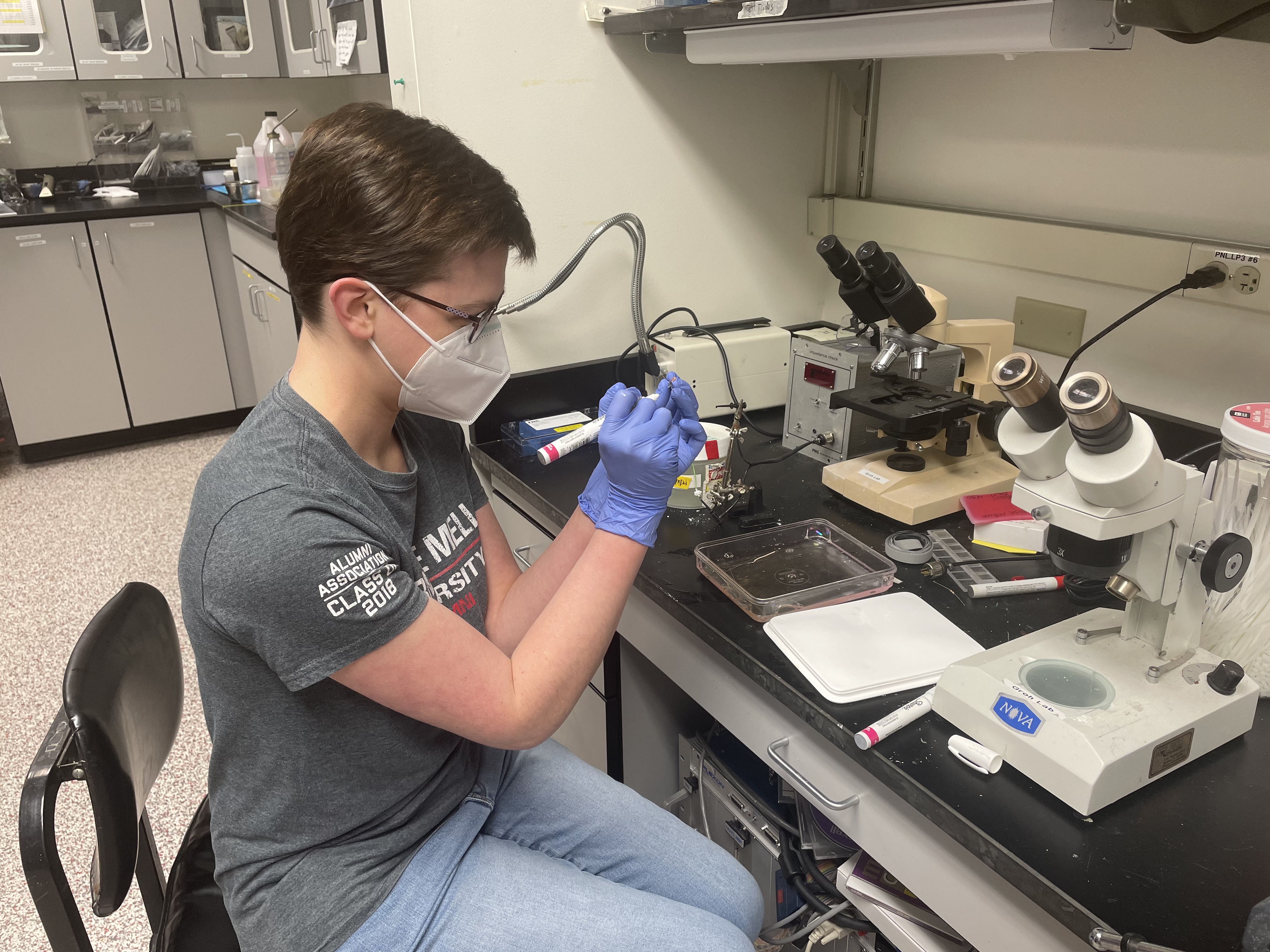

And in between, she’s researching how the brain combines vision and hearing at Duke University as part of her Ph.D. studies in neurobiology.

“When I was a kid, I had a lot of extracurriculars,” says Meredith, a 2018 Mellon College of Science graduate with degrees in neuroscience and psychology. “Then when I was at CMU, I was involved in many different clubs, many different leadership positions, and now that has carried through to graduate school.”

“To me, it's really important to do all of these things. I’m not doing my policy and community engagement as an afterthought, I’m focused on really integrating it into my research as well.”

"CMU taught me how to do a lot of things all at once and do them well, which is something that I have really carried forward to be able to balance my research with the other things that I do now."

Interdisciplinary Ideas

Like many Tartans, Meredith arrived at CMU with interests in many different areas, and she didn’t want to choose just one path. She knew she enjoyed science as a whole, and eventually, she narrowed to two areas — neuroscience and psychology.

“I wanted to get this dual perspective: what is the biology of the brain, what makes us who we are, how do we work as people, and then how does it make us work at the behavioral level as well,” Meredith says.

She dove into her research. Working with mice, she taught them to follow the trail of a scented crayon.

“I really have some fond memories of my first time learning how to do research, learning how to train a mouse, figuring out what to do and seeing how the actions that I would take could make the mouse do different things,” Meredith says. “It was exciting, and it laid the foundation for my Ph.D.”

She also found plenty to learn from her fellow Tartans, too.

“CMU is so strong in so many fields, I could explore all my interests,” Meredith says. “There was just this collaborative energy that I haven’t necessarily found anywhere else.”

Meredith embraced that energy: playing the cello in two orchestras, co-directing alternative spring break and visiting local schools for STEM events with NeuroSAC, the Neuroscience Student Advisory Council.

At the local schools, NeuroSAC members provided students with interactive neuroscience activities. They affixed small stickers to the arms of two different children. The stickers were connected by small wires, and a miniscule electrical current ran through the wires. When one person moved their arms, the other person got a tiny zap making their arm move involuntarily.

“It’s cool because you can’t resist it,” Meredith says. “Your arm will move no matter what. It was a way to explore how our nerves work, and that was often their first exposure to that idea.”

“As my research work laid the foundation for my Ph.D., opportunities like visiting schools really laid the foundation for my work in policy, writing and all of those other things.”

“We need to remove barriers that make professions in STEM inaccessible, and we also need to remove barriers that keep the benefits of science from reaching everyone in the global community."

Breaking Barriers

While Meredith loved visiting schools, she soon came to a realization.

“I used to believe the key thing that we needed to do was just recruit people into science. That was one of the reasons that I got into outreach as an undergrad,” Meredith says. “I thought if we just get kids really excited about science, they'll be more likely to pursue careers in STEM.”

“Now, I think that alone isn't really a complete solution because, for example, underrepresented groups are still going to face barriers in STEM workplaces, and so, just bringing more people into those spaces on its own doesn't really help.”

She describes her work as a science communicator and policy advocate — writing award-winning pieces for Scientific American and Massive Science; serving as Public Engagement & Communications chair for the National Science Policy Network; and training scientists to write in simplified terms for the common person as part of NPR’s SciCommers — as barrier-breaking.

“We need to remove barriers that make professions in STEM inaccessible, and we also need to remove barriers that keep the benefits of science from reaching everyone in the global community,” Meredith says.

For her, it's sharing science with people and integrating that communication with policy and advocacy, so that the world can use science for the common good.

She envisions a society where it’s the norm for scientists to advocate in their communities, talk to policymakers and publish in news outlets — and for non-scientists to have the baseline knowledge and skills to use science every day, whether that’s determining their next vote or investigating a medical treatment.

“We all have to use scientific thinking, critical thinking in our daily decision-making,” Meredith says. “So I’m working to bring more people into science but also helping people who aren't scientists benefit from the science that we are producing.”