School of Design

There and Back Again

The Incredible Journey of the MoonArk

written by

Joe Lyons

On Monday, Jan. 8, Peregrine Mission One, the first privately funded lunar lander by Pittsburgh’s Astrobotic Technologies, achieved lift off at 2:18 a.m. from Cape Canaveral carried by ULA’s Vulcan Centaur rocket. On board the lunar lander was an assortment of payloads. From the scientific, including the Iris Rover from Carnegie Mellon University, to the commercial, to the deeply personal, Peregrine and its cargo was poised to be America’s return to the lunar surface for the first time in 50 years — illustrating the viability of private delivery services to the moon as part of the NASA CLPS (Commercial Lunar Payload Services) program.

The MoonArk, a cultural marker that combined the arts, humanities, sciences and technologies to help tell the story of humankind, was one of the most precious and important payloads.

Spanning 15 years and containing the collaborative works of hundreds of international contributors, the MoonArk started its life as part of a larger Moon Arts research project initiated by Professor Emeritus and pioneering space artist Lowry Burgess in the Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry. Lowry and his team’s vision was to put the first museum on the moon to elevate the conversation around humanity’s expansion into the Solar System.

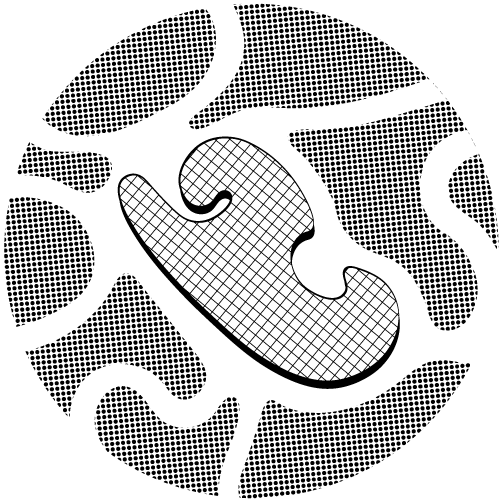

Comprising four independent chambers and weighing a total of 10 ounces, the MoonArk contains hundreds of images, poems, music, nano-objects, mechanisms and earthly samples intertwined through complex narratives that blur the boundaries between worlds seen and unseen. It is designed to direct attention from the Earth outward, into the cosmos and beyond, and reflect back to Earth as an endless dialogue that speaks to humanity's context within the universe.

Fabrication of the MoonArk has instigated the innovation and invention of digital fabrication techniques, ultra-high-resolution imaging, and other advances in material science, technology and the arts. It has also engaged colleagues across the world who dared to offer something beautiful for humans to discover in the very distant future. The project involved 12 units at Carnegie Mellon University, 18 other universities and organizations, 60 team members and more than 250 contributing artists, designers, educators, scientists, choreographers, poets, writers and musicians.

Intricate, complex and beautiful, the MoonArk is an engineering marvel. While it appears fragile and light, it was tested beyond its limits and proven to be able to withstand the rigors of space travel and endure the harsh conditions of lunar surface where it could reside for thousands of years. While never the intention, the MoonArk team became experts in the field of space art and cultural payloads. Their approaches and methods instigated new attitudes for the space art community and achieved implausible durability. Between Astrobotic’s origins here, the Iris lander and the MoonArk, Carnegie Mellon University has proven their readiness to tackle projects aimed at the stars.

"The whole spirit of the project is about cooperation, celebrating our creative capacity and illustrating how we are moving forward together. It is highly aspirational to send a sculptural object to the moon to endure for hundreds of thousands of years, and it's also a very hopeful piece."

Mark Baskinger

Associate Professor, School of Design

Director, MoonArk

"Context is such an important part of deconstructing art, and when you remove those contexts you have a whole new set of challenges," added Professor and MoonArk Project Manager Dylan Vitone. "We wanted to build a narrative off of our universal experiences that's moving to people now, but also 1,000 years down the road."

After all these years of work, development and multiple tours to museums all over the world, the MoonArk finally took flight.

Sadly, seven hours into the mission, a problem was reported with the propulsion system on the lander. A gradual propellant leak had compromised the mission and while the lander would go on to achieve its goal of reaching lunar distance, an actual soft landing on the moon was going to be impossible. The MoonArk’s goal of being a cultural marker to inspire wonder a thousand years into the future was unfortunately out of reach.

For several days after the incident, the MoonArk reached about 242,000 miles from Earth while the team at Astrobotic used the time in cis-lunar space to collect data, run tests and learn as much as possible before the lander would have to make its return to Earth. That return to our atmosphere would also mean the end of the lander, its payloads and the MoonArk. On January 18, the MoonArk, aboard Peregrine, entered into the South Pacific along the Tropic of Capricorn.

“The MoonArk joins the small pantheon of space art projects,” said Baskinger. “Our mission to the moon continues with current projects based on the incredible knowledge we’ve gained and experience in balancing creative vision with the material realities of space travel.

“We sent a gift to the moon. It wasn’t there at the time to receive it, so we’ll try again.”

"The project for me was always about faith, and the beauty of so many people from around the world working toward a greater, shared narrative of what brings us together as a planet. It is a little bittersweet not being able to look out at the moon and know what we accomplished, but I guess becoming a ‘shooting star’ is pretty poetic in its own right."

Dylan Vitone

Associate Professor, School of Design

While the fate of the moon-bound MoonArk is a tragic loss, the content of the MoonArk is not entirely lost. The MoonArk’s identical twin remains in the permanent collection at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, where it is preserved for future discovery.

"I am so very grateful it ended up at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum," Vitone added. "We spent the majority of the hours on the majority of the days on the majority of the weeks over the better part of 15 years dreaming up the MoonArk and making it real with a large group of amazing people. It’s an honor to be housed in such an amazing institution. It is a museum that is about human triumphs in technology and large groups of people working together in aspiring for something greater than just the individual accomplishments.

"We hope in a very small and humble way that is what the MoonArk embodies.”

The Moon Arts Group at CMU is pursuing their next project, called “Lunarglyphs,” a system of modular cultural components that integrate with spacecraft to continue telling the story of humanity.

"As we head further into the Solar System, we must consider that the vehicles and apparatus we use will become our cultural markers that will leave an indelible imprint on pristine environments humans have not yet touched."

Mark Baskinger

“MoonArk brings this into focus for critical conversation today and should inspire more ambitiously beautiful creative practice that expands our perception and our reach.”

featuring the following:

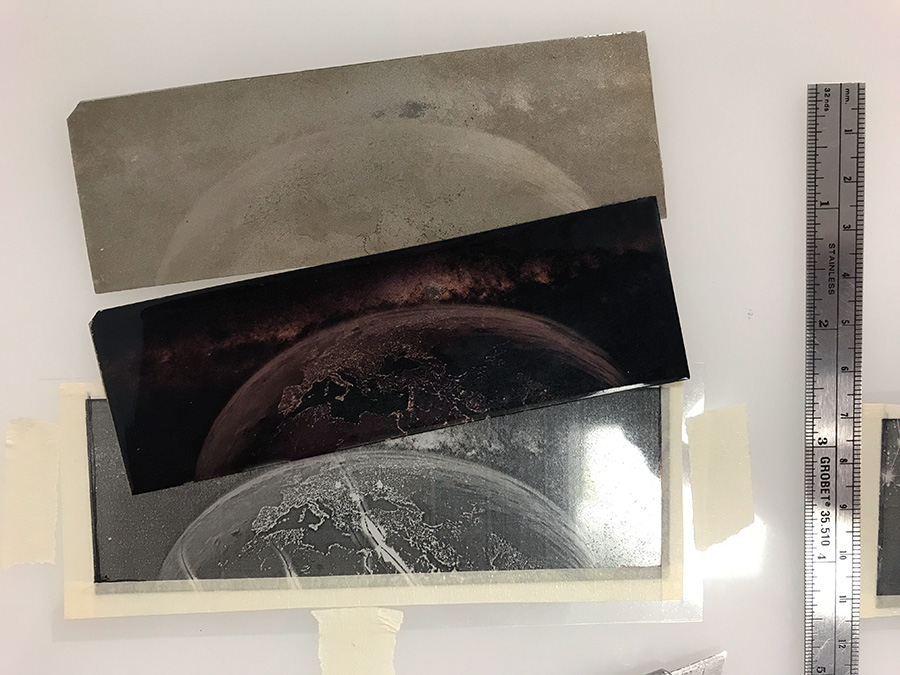

MoonArk images by Dylan Vitone

engraved murals image by Mark Baskinger

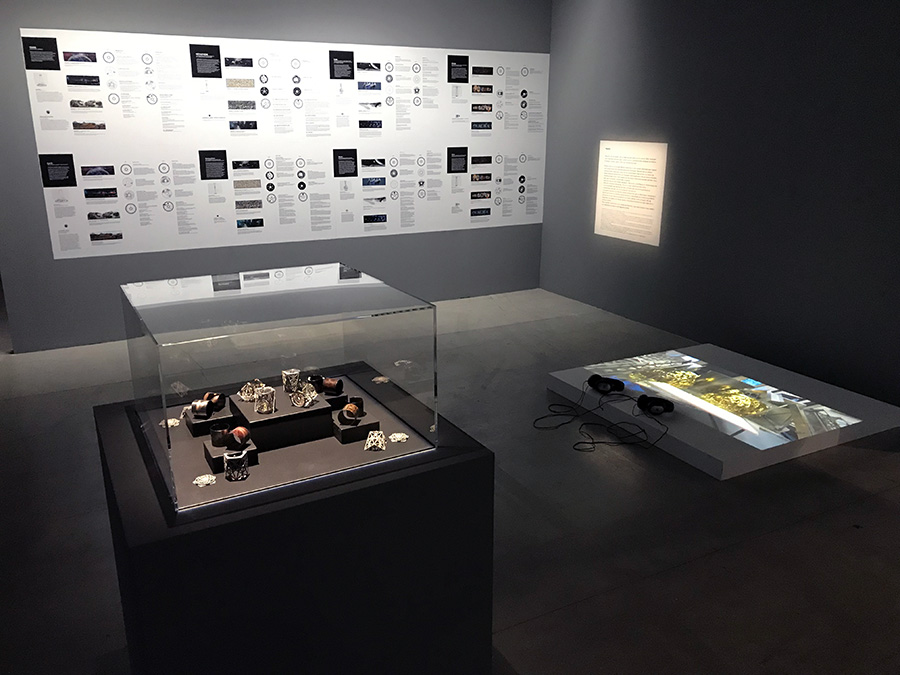

Pompidou installation image by Dylan Vitone

MoonArk team install image by Jocelyn Mackay