Researchers Unveil New Password Meter That Will Change How Users Make Passwords

By Daniel Tkacik

PITTSBURGH – One of the most popular passwords in 2016 was “qwertyuiop,” even though most password meters will tell you how weak that is. The problem is no existing meters offer any good advice to make it better—until now.

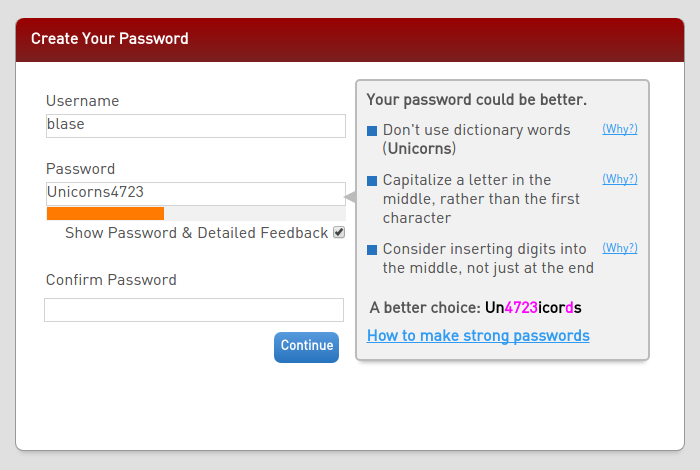

Researchers from Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Chicago have just unveiled a new, state-of-the-art password meter that offers real-time feedback and advice to help people create better passwords. To evaluate its performance, the team conducted an online study in which they asked 4,509 people to use it to create a password.

“Instead of just having a meter say, ‘Your password is bad,’ we thought it would be useful for the meter to say, ‘Here’s why it’s bad and here’s how you could do better,’” says CyLab Security and Privacy Institute faculty Nicolas Christin, a professor in the department of Engineering and Public Policy and the Institute for Software Research at Carnegie Mellon, and a co-author of the study.

“Instead of just having a meter say, ‘Your password is bad,’ we thought it would be useful for the meter to say, ‘Here’s why it’s bad and here’s how you could do better,’” says CyLab Security and Privacy Institute faculty Nicolas Christin, a professor in the department of Engineering and Public Policy and the Institute for Software Research at Carnegie Mellon, and a co-author of the study.

The study will be presented at this week’s CHI 2017 conference in Denver, Colorado, where it will also receive a “Best Paper Award.” A demo of the meter can be viewed here.

“The key result is that providing the data-driven feedback actually makes a huge difference in security compared to just having a password labeled as weak or strong,” says Blase Ur, lead author on the study, formerly a graduate student in CyLab and currently an assistant professor at the University of Chicago’s Department of Computer Science. “Our new meter led users to create stronger passwords that were no harder to remember than passwords created without the feedback.”

The meter works by employing an artificial neural network: a large, complex map of information that resembles the way neurons behave in the brain. The team conducted a study about this neural network approach that received a Best Paper Award at the USENIX Security conference in August 2016. The network “learns” by scanning millions of existing passwords and identifying trends. If the meter detects a characteristic in your password that it knows attackers may guess, it’ll tell you.

“The way attackers guess passwords is by exploiting the patterns that they observe in large datasets of breached passwords,” says Ur. “For example, if you change Es to 3s in your password, that’s not going to fool an attacker. The meter will explain about how prevalent that substitution is and offer advice on what to do instead.”

This data-driven feedback is presented in real-time, as a user is typing their password out letter-by-letter.

The team has open-sourced their meter on GitHub.

“There’s a lot of different tweaking that one could imagine doing for a specific application of the meter,” says Ur. “We’re hoping to do some of that ourselves and also engage other members of the security and privacy community to help contribute to the meter.”

Other authors on the study included current CMU students Jessica Colnago, Henry Dixon, Pardis Emami Naeini, Hana Habib, Noah Johnson, and William Melicher; former CMU students Felicia Alfieri and Maung Aung; and Carnegie Mellon faculty Lujo Bauer and Lorrie Faith Cranor.