August: Education

This month, as the country begins to return to schools — albeit a bit differently this year — we too are setting our minds on education. Throughout EPP Projects' history, educational policy issues have been one of the more prominent focuses. Join us this month as we explore how past EPP Projects took on educational policy challenges of the day and how their results helped us anticipate the educational needs of tomorrow.

The Fall 1993 project, The Internet in K-12 Education, wanted to explore how this new tool, the internet, could be used in a more prominent way in K-12 education. The results of the project found that there were numerous pros but also quite a few cons to the implementation of the internet in the classroom and in at-home school work. Teachers were excited about the prospect that you could be anywhere in the world and still connect with your students. Teachers found the internet valuable in that it expanded the number of resources available to them by taking advantage of tools and programs that are available via the web. Teachers also found that the type of activities that can be done online can be easily adjusted according to your target group. Lower-grade levels had strongly structured activities, moving to less guided activities as the grade level increased. However, the teachers did note a few major shortcomings, with the largest concern being accessibility. While the internet was a great resource for education while in the classroom, many students didn't have access to a computer or reliable access to the internet outside of school, rendering any computer-based homework impossible to a large portion of the student population.

Holding onto that concept, the Spring 1996 project, Ensuring Equal Access to Information and Computer Technology, wanted to better understand the kinds of inequity that was occurring relating to access to computer technology in Allegheny County. The goals of the project were first, to investigate the status of available access in Allegheny County and second, to build tools to analyze the possible solutions to fill the gaps in access in Allegheny County. Through the utilization of a GIS (Geographic Information System) model the group was able to determine the current access levels in the county and predict improvement resulting from the placement of more access points. The GIS model showed a tremendous increase in computer accessibility as a result of the libraries, which serve as access points for those who don't have personal computers, but found gaps in computer access in Allegheny County and places where additional access points could be added to increase overall access to information technology. The group recommended that Allegheny County install computer kiosks and computer clusters throughout Allegheny County. They recommended that these technological access points should be publicly owned and located in high traffic areas to give as many people access as possible.

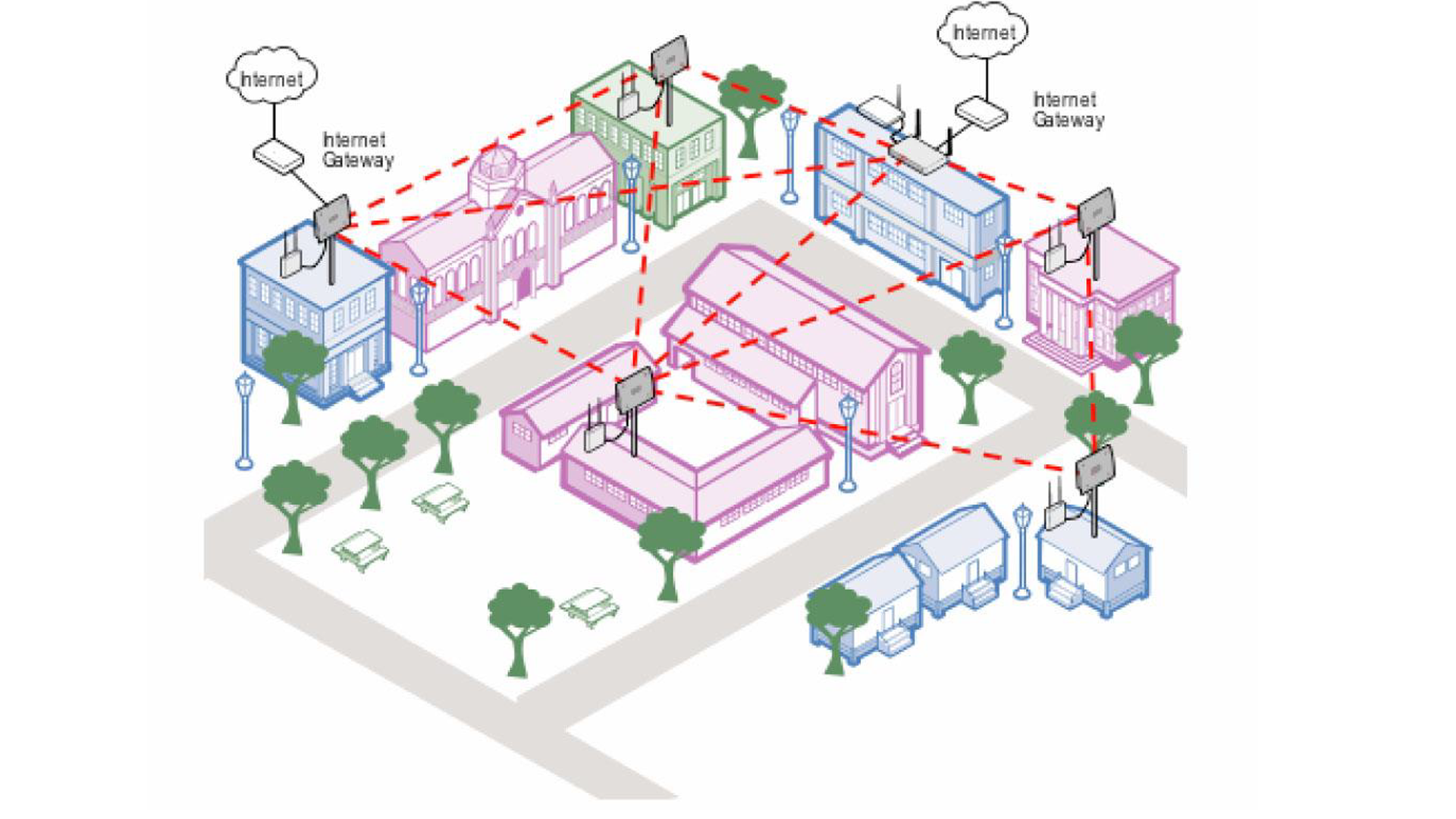

The solution the Spring 1996 project group proposed to the lack of computers in Allegheny County is very similar to solutions that numerous organizations are trying to implement in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has highlighted the need for widespread, reliable broadband home internet and additional personal computers in the homes of students around the country. In March, Pittsburgh Public Schools created a home technology survey to determine the proportion of students who have devices and internet access at home. Of the respondents — which account for roughly 77% of PPS students — 41% of families indicated they do not have enough devices for each of their children. About 1,533 students — about 7% of PPS students — responded by saying that they do not have internet access, although PPS expects that the actual percentage is higher when accounting for the 3,649 students whose families did not respond to the survey. “Depending on the neighborhood, you're looking at up to 70% of homes not having broadband internet access,” said Adam Longwill, executive director of Allentown nonprofit Meta Mesh, “So depending on where you are, it's either 2020 or 1995.” Organizations such as Meta Mesh, Computer Reach, Neighborhood Allies, and All Lines Technology are all stepping up to try to provide as much community Wi-Fi and personal computers to at-need households, but they can only do so much. Many of these issues stem from income inequity, and poorer homes tend to have less access to computer technology. But, there does seem to be a solution out there that can bridge the divide and reach communities that don't have access to computers while still offering educational services. And wouldn't you guess it, an EPP Projects course looked at this policy problem years ago?

How Meta Mesh configures their community Wi-Fi networks

How Meta Mesh configures their community Wi-Fi networks

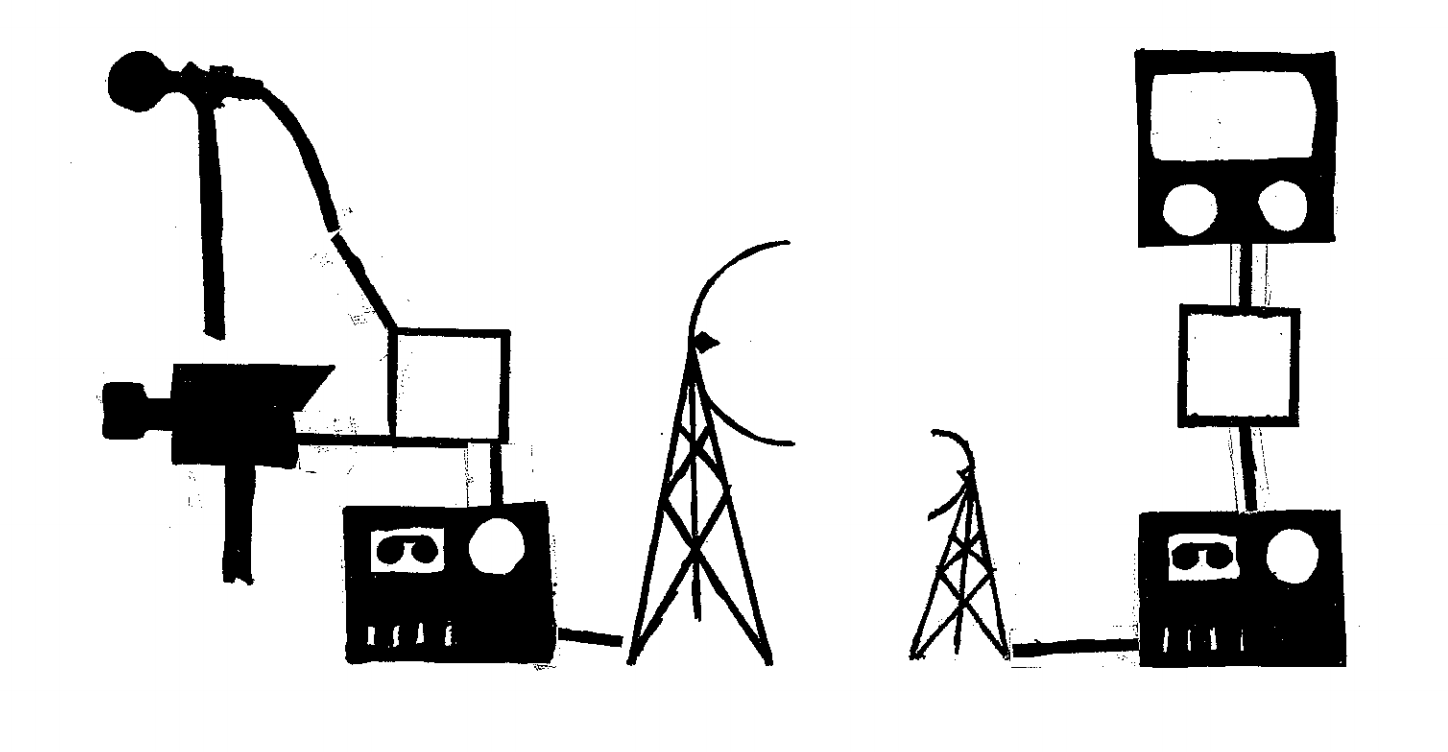

The Spring 1978 project, Instructional Television: Prospects for Application to Continuing Education in Pittsburgh and the Surrounding Tri-State Area, saw rapid progress in educational television technologies during the '70s and wanted to explore how this medium of technology could be used in a bigger way. A systematic study of available instructional television technologies was undertaken and these technologies assembled into complete delivery systems. The project group found that ITFS (Instructional Television Fixed Service) — a band of twenty microwave TV channels available to be licensed by the U.S. Federal Communications Commission to local credit-granting educational institutions — would be the most feasible option to provide educational television to the masses. Another option in the report that is a Community Education Channel — one channel designated for the sole purpose of educational community communications.

Today, ideas like this ones proposed in the Spring 1978 project are coming into popularity with the growing concern over the lack of widespread broadband internet access. This past spring, New Jersey’s public television station, NJTV, began working with the state’s teachers’ union to produce school programs after learning that 300,000 of the state’s children had no internet access. From April until the school year ended, grades three through six each had an hour of programming on the station every morning. Further from campus, in Peru, a poor country where only 15% of public school students have access to a computer at home, broadcast lessons have become the dominant mode of learning during the pandemic. In a government survey in June, three-quarters of parents said their children used the televised programs, compared to a quarter who used the government’s educational website. Television holds promise as a low-cost complement to online schooling and a lifeline for students with few other resources.

Modern problems often require modern solutions, but sometimes having the foresight to anticipate the larger issues of tomorrow puts us in a better place to implement solutions in an ever-changing world — exactly the thing EPP Projects does best.

The ITFS system

The ITFS system