CMU Physics Faculty Trains High School Teachers

Media Inquiries

Elizabeth Giles taught John Alison(opens in new window) his first physics lesson. But last year, she took lessons from him.

Giles, a physics teacher at Baldwin High School, was one of a number of local teachers who have participated in Carnegie Mellon University's Physics Teachers Program(opens in new window) organized by Alison, an assistant professor in the Department of Physics(opens in new window). In its third year, the program provides opportunities to high school educators, resources and a community aimed at motivating more students to consider physics as a career.

"It's a double whammy of benefits," Giles said. "I love the chance to talk to other high school physics teachers and getting insight into what is needed for students to be prepared for college."

Having begun during the COVID-19 pandemic, the program has evolved based on feedback from previous sessions.

"We want to get more people involved in physics. Students have already made up their mind about what they want to study by the time they get to college," Alison said. "It's really the high school teachers who make the difference. Many people in the physics department got excited about the field because they had really good and interesting physics teachers in high school, and that helped set them on their path. If we want to grow the physics population, that's where we have to start."

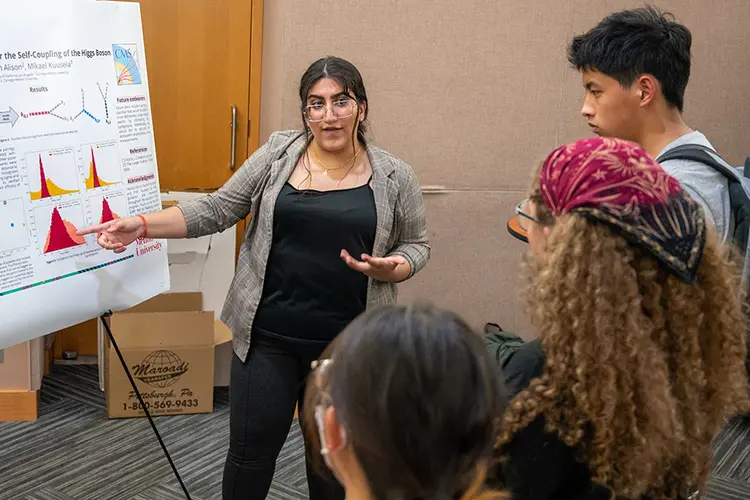

Along with discussions about Carnegie Mellon research in particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, biological physics, and condensed matter physics, teachers will tour lab spaces and meet faculty, staff and students.

"Last year undergraduates talked about what they thought about the AP exam as well as their college and high school courses," said Giles, who had planned on attending this year's event but had a family conflict. Teachers who attend the program come from all types of schools. Baldwin High School requires every student to take at least one physics course.

"We have three full-time high school physics teachers, so I had people down the hall for me to bounce ideas off of," said Giles, who recently retired. "A program like this is so valuable for teachers who don't have that opportunity."

Penn Hills High School physics teacher Katharine Gorman has participated in the program since its inception.

"People don't go into physics because of Isaac Newton, but his work is foundational to what is taught in high school physics," Gorman said. "What makes physics more engaging is showing the students where the field has gone in the past 400 years."

This year's program focused on developing programming skills. Faculty, graduate students and undergraduates worked with teachers to design and implement Python programs that can be used to visualize physics problems and solutions in classes. Alison said he asked teachers to think about a classroom physics concept that they would like a visual explanation of, such as centripetal motion.

Gorman sees an opportunity to take that idea a step further this fall.

"There's a huge overlap between kids in AP physics and in our Coding 3 class," Gorman said. She and other teachers at Penn Hills have been brainstorming ways to approach physics that combines the two disciplines. "One of the things that would be really good is to work on some kind of project where the students build video games with realistic physics in them."

The four-day program took place June 26- 29. On the last day, teachers were encouraged to bring an administrator or another teacher to learn about the program and to hear about career opportunities related to physics.

According to Alison, one of the misperceptions about physics is that the only job path is to be a teacher.

"Most people who get a physics degree aren't physics professors. They're also not working in pure physics," Alison said.

A physics background provides students with essential problem-solving skills and teaches them how to think about hard problems. The American Physical Society offers a career guide to showcase different pathways where a degree in physics can be beneficial: in fields such as nuclear power, astronomy and space, medical physics, optoelectronics, quantum technologies, and software engineering. Students with physics backgrounds also tend to do well on the MCAT examination if they're interested in medical school or the LSAT if they want to pursue a law degree.

Alison said that exposing high school teachers to advances in the field can have a multiplier effect.

"Each teacher has the potential to reach 20, 50 or more students in a year. The reach is so much larger and then creates a community," he said.

As part of that community, Department of Physics Head Scott Dodelson(opens in new window) said Carnegie Mellon should be a resource for teachers and local students. Along with the teacher training program, the department has graduate student assistantships that support physics outreach to local high schools.

"There are huge inequities in the world, and education is a leveler," Dodelson said. "It's our responsibility to reach out as far as we can to help expose people to what an intellectual life is so that it can be part of their aspirations. Through outreach efforts by the Department of Physics, we're trying to attack this problem in a variety of ways."

Teachers who participated in the full program and completed the evaluation form, which is used to learn about the needs of the educators and to improve future offerings of the program, earned 20 Pennsylvania Act 48 hours and a stipend of $50 provided by Carnegie Mellon's Leonard Gelfand Center(opens in new window) and the Department of Physics. Parking and lunches were also provided.

Judith Hallinen(opens in new window), the broader impacts and education outreach consultant for Carnegie Mellon and former director of the Gelfand Center, said that Pennsylvania Act 48 requires educators to participate in professional development to maintain active educator certification. The university provides several opportunities to help complete this goal, and faculty with funding from the National Science Foundation often have education outreach components as part of the broader impact requirements of their grant deliverables.

"It is important for Carnegie Mellon faculty and staff to share information with educators about cutting-edge research, careers in a variety of fields, and pathways to those careers so the teachers can provide accurate information to the students in their classroom," Hallinen said.