CMU’s Iris Rover: A Heartbeat in Space, A Legacy on Earth

For Carnegie Mellon University’s Iris team, every moment seemed to bring a new challenge with it — and they turned every challenge into an opportunity

Media Inquiries

Shortly after the Jan. 8 liftoff of United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan rocket with their rover on board, Carnegie Mellon University's Iris team contingent, consisting of about 30 students and a handful of staff, filed into their rental house in Florida.

Hours after rousing speeches from team leadership, hopeful messages and the perfect launch, they learned that Iris, the lunar rover built by 300 students from across CMU’s seven colleges, wouldn’t make it to the moon. An anomaly in Astrobotic’s Peregrine lander, to which Iris was bolted, would likely prevent a soft landing on the lunar surface.

Rather than find themselves discouraged, the students immediately jumped into action. They transformed their rental home into an impromptu command center and decided to make the most of any time remaining in its journey. Team members extended their stays in Florida, booking hotels or staying with relatives as events unfolded.

“Our team wanted to figure out what we could do to better science, or any technical capabilities of our rover,” said Nikolai Stefanov, the mission control lead for Iris. “Basically it boiled down to a bunch of all-nighters in a vacation home.”

The living room, kitchen, dining room and patio all became workstations where the crowd broke into their respective teams. An air mattress was inflated and propped up vertically to form a wall, cordoning off areas to maximize focus and privacy. A couch became a favored spot for sleep-deprived team leadership, who needed to be a shout or shake of a shoulder away from handling any crises. Smartphone hotspots became a way to preserve bandwidth and ensure redundancy.

“It was a blessing in disguise, having everyone working together all in the same house,” said Carmyn Talento, the representation team lead for Iris. “When you needed somebody’s expertise or opinion, all you had to do is go poke someone, go wake someone up. Everyone was always willing and eager to put their efforts toward something.”

Iris wouldn’t be a rover in the traditional sense, but it was still a space-faring object that was actively making history. The team dropped everything to make sure that it continued to do so. When the team was able to retrieve information and check the status of Iris’ systems from hundreds of thousands of miles away, they knew that it was a success story unlike any other: a heartbeat in space. It was proof that years of hypothesizing, building and testing had worked, even in the face of uncertainty.

“There was an eruption of cheering,” Talento said, “a new wave of hope.”

Not dead yet

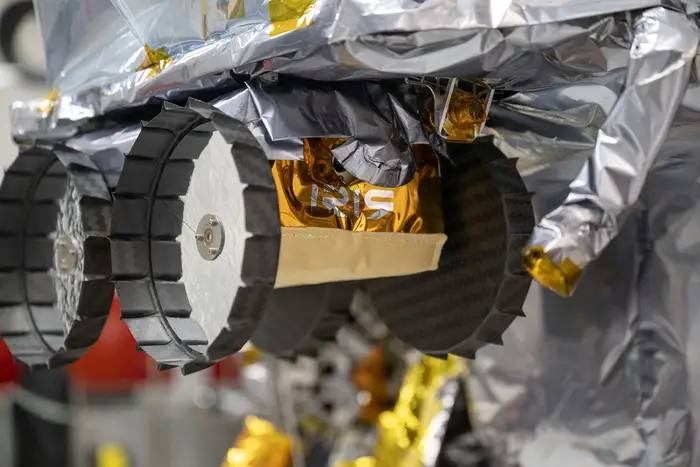

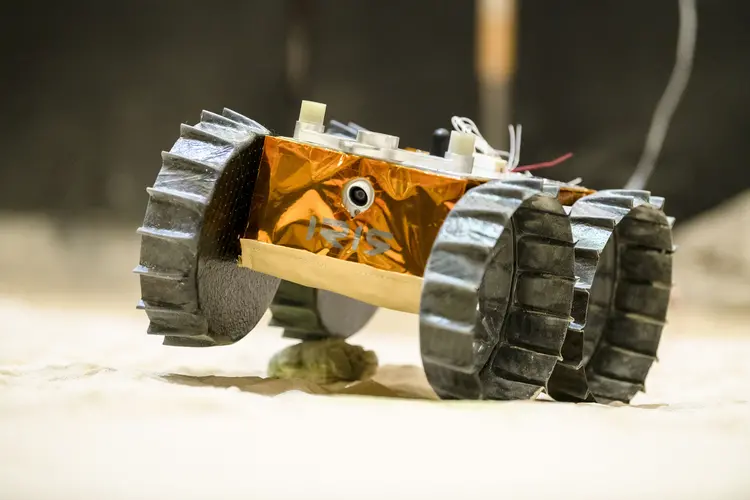

The 2.2-kilogram rover, powered by a custom single board computer, was the first of its kind to survive a launch and a zero-gravity environment. Printed directly on the board were the names of dozens of engineers who contributed to the rover’s journey. Its primary systems, tucked within a shoebox-sized carbon fiber chassis, performed well as the rover endured extreme temperatures and high levels of radiation. Even through lapses in signal and changes in objective, Iris persevered.

The mission continued, but so did the issues. The team faced several interruptions on the ground. Planned communications outages meant that they were unable to check its systems for excruciating periods of time. A tornado warning sent the team into a frenzy. A fire alarm went off. At one point, a mix-up between a thermostat and the house’s security system brought the police to their rental. Still, none of it stopped them from their new goal of receiving data and testing systems as Iris soared through space.

“The team worked around the clock — there's no time of day in space," Talento said. "There's no a.m. or p.m. You either have signal, or you don't have signal. We work with what we've got, and as students, we’re going to want to work.”

(opens in new window)By the time Peregrine started to swing back toward Earth, Iris became much more than an engineering project. For the students, it became a symbol of resilience and a testament to their ability to pivot on the fly. A few short days after the initial launch, the Iris team posted a meme on Instagram depicting the rover as a Monty Python character, declaring defiantly, “I am not dead yet!”

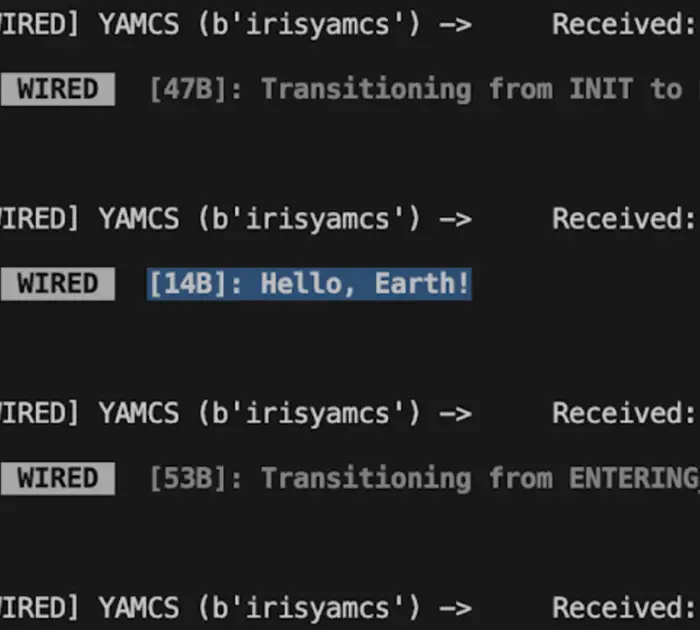

They followed by sharing that they had achieved two-way communication with the rover in space, receiving a message in real time from Iris: a cheerful, “Hello, Earth!”

As Peregrine continued its egg-shaped orbit around the planet, the team brainstormed ways to make the most of its battery life and remote capabilities.

Only the beginning

Iris returned to Earth’s atmosphere above the remote South Pacific Ocean on Jan. 18, and disintegrated upon reentry. While Iris’ journey didn’t go as planned, the students succeeded in building a piece of space-faring technology that has made it farther from Earth and closer to the moon than any student-built rover has to date.

“Ultimately it comes down to having a team that works well together, is confident and throws ideas out, however crazy they might be,” Talento said. “Speak your mind, and someone will take it, someone will run with it, and together we’ll figure it out.”

There are currently no plans for an “Iris 2.” However, the technology and action behind Iris lays substantial groundwork for future space, robotics and engineering endeavors at Carnegie Mellon. Raewyn Duvall(opens in new window), the Iris program manager and a rover executive director, noted that the team’s work has already made a substantial impact on space and robotics work at CMU.

“A lot of lessons learned have already gone into projects like MoonRanger(opens in new window),” said Duvall, who was previously at NASA. In one instance, before delivering Iris to Astrobotic, an opening needed to be made on the rover to access difficult-to-reach internal electronics so that software updates could be made after delivery. This inspired an approach to incorporate more direct access points into the designs of future projects. “The question of, ‘How do you future proof?’ is something most students don’t think of. Building it into the procedures future projects will use is a really big thing.”

But perhaps more importantly, Iris and its student team have established a legacy of teamwork and inclusion. “One of the goals of Iris at a fundamental and broad level is to open up space to more people,” Talento said. “If we’ve learned anything from this, it’s that that’s a good idea and needs to happen sooner rather than later.”

International contributions to the project meant that the team was able to bring in perspectives that seldom make their way into other institutions in the industry. “We were fully a university project, so were able to work with international students who would not otherwise be able to due to proprietary issues,” Duvall said.

Additionally, the Iris team comprises individuals from a wide range of academic backgrounds, ethnicities, cultures, sexual orientations and gender identities to form a welcoming environment. “They have become such a family,” Duvall said.

“Especially after being stuck in a house together,” Talento added. “We have the annoying younger brother trope, the strange cousin … ”

“ … the separated dad who comes back for all of the cool events,” Duvall added jokingly. “There are all of those roles.”

The experience allowed the current students, many of whom are members of Gen Z, to form relationships that will likely last a lifetime while setting records and achieving scientific marvels.

"Iris' legacy is to open up space to students, to young people, to enthusiasts, to dreamers," Talento said.

Reentering Earth's atmosphere? Here are the essential songs from a group of students who have been there.