Energy Modeling and the Demise of Chevron

By Christopher Galik, Professor, School of Public and International Affairs, NC State University

What do a pair of Gorsuchs have to do with the fundamental relationship between the U.S. Executive, Legislative, and Judicial branches? And what does any of this have to do with power sector modeling? The short version is, quite a bit.

In 1981, the Natural Resources Defense Council challenged a decision by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, led at the time by Anne Gorsuch Burford, to change its interpretation of the word “source” under the Clean Air Act. Though the lower courts decided against the Agency’s action, the decision was appealed by Chevron Corporation to the Supreme Court, which agreed to take up the case.

The resulting decision, Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. (1984; 468 U.S. 837), was to set precedent for decades of regulatory and judicial decision-making. Siding with the EPA and reversing the lower court, the decision in Chevron held that agencies were entitled to a certain deference when making interpretations of otherwise-ambiguous statutory language. The two-part test that emerged would serve to guide judicial review of agency decisions for nearly four decades. What would come to be known as the Chevron doctrine required judicial review to first determine whether the statute in question was ambiguous in its direction. If not, the agency must implement the law as written, full stop, end of story. In situations where the authorizing statute was ambiguous, however, Chevron held that courts should defer to an agency’s interpretation of how to implement that law (subject of course to limits of reasonableness of that interpretation).

Ok, but what does that look like in practice? Well, in 2015, for example, the U.S. EPA argued in the final rule promulgating President Obama’s Clean Power Plan that “[i]n the absence of specific direction or enumerated criteria in the [Clean Air Act] concerning what pollutants from a given source category should be the subject of standards, it is appropriate for the EPA to exercise its authority to adopt a reasonable interpretation of this provision” (80 FR 64530; October 23, 2015). Specifically citing Chevron, the U.S. EPA concluded it had a “rational basis” for regulating CO2 emissions from fossil fuel power plants.

Fast forward a few more years. With Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch—Anne Gorsuch’s son—siding with a 6-3 majority, the Supreme Court held in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo that the central premise of the Chevron case was decided in error. Citing the Administrative Procedure Act, the Supreme Court in Loper Bright returned authority for determination of the appropriateness of an agency’s action squarely to the courts. No longer were agency interpretations to be given such strong deference in judicial review.

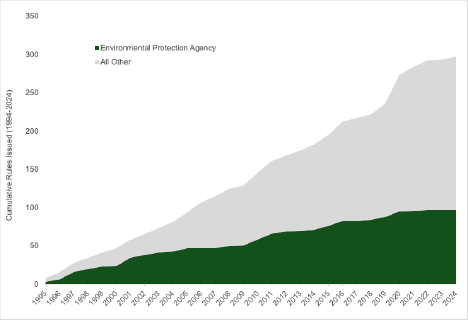

That’s my non-lawyer’s version of the legal history, but what does any of this have to do with energy in the here-and-now? Again, quite a lot. Looking back in time, Chevron stood for forty years, in which time a great deal of regulatory decision-making has occurred. These are decisions that were made (and occasionally later challenged in court and upheld) assuming strong deference to agency interpretations. A quick search of the Chevron citation in the Federal Register—the official record of U.S. regulatory activity—shows that 318 separate final actions citing the case have been taken since 1994 (as far back as we can go with a text search). These 318 actions are scattered across 18 separate agencies, but rules issued by the EPA make up nearly one-third. A majority of those issued by the EPA pertain to energy in some fashion, be it air pollution, vehicle fuel economy, or renewable fuels. Though the majority opinion in Loper Bright took pains to note that previous decisions relying on Chevron were not automatically overturned by simple virtue of the decision, the possibility exists that new challenges to past agency actions could soon follow.

Cumulative rules issued citing Chevron since 1994. Source: Federal Register (last accessed August 23, 2024).

But the net effect of the Loper Bright decision may not be as dramatic as it might first appear. As I teach in my environmental policy seminar, U.S. legislation has become increasingly specific in recent years, reducing the scope for agency interpretation. This trend is itself partly due to concerns that laws won’t be implemented pursuant to Congress’s wishes unless they are clear in intent and direction. For example, specific considerations for agencies to undertake when developing implementing regulations and the presence of so-called hammer clauses forcing decisions to be made under particular timelines or conditions have all become more common in recent decades. It’s not a perfect apples-to-apples comparison, but just compare 2022’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to 1973’s Endangered Species Act (ESA). Sure, the 274-page IRA has been hailed as the single most impactful climate law to date, but the ESA holds tremendous influence over a vast swath of private and federal actions and does so in just 41 pages of text, leaving a great deal open to interpretation.

Of course, that’s not to say that there won’t be challenges to programs. After all, much of the recent fights over climate and energy have taken place in the context of EPA’s interpretation and implementation of the Clean Air Act, a law that has been revised and updated over the years, but one that still retains a decade’s-old legislative architecture. At least under the current administration, less reliance has been placed on Chevron to defend agency determinations—possibly in recognition of the potential for it to be eventually overturned—something that is again visible in EPA’s flat-lined citation of Chevron in the figure above.

Going forward, the decision in Loper Bright will surely continue the trend toward increasing specificity in legislation. This increasing specificity will require analysis upfront to ensure, to the maximum extent possible, that specifically-worded legislative provisions will have the intended effect. Particularly given political polarization and the difficulty of passing major legislation of any sort, options to tinker with or fix provisions are likely to be few and far between, increasing the need to understand the effects of a law before it is ever even voted on. That’s where the modeling community comes in. Indeed, we saw this in the case of the IRA, a law that was seemingly developed and evaluated in real time. Unfortunately, an increasing trend toward specificity could also tie the hands of future administrations and limit their ability to adapt to new, previously unforeseen situations, calling for an even wider array of approaches and perspectives to be deployed at the time of legislation development.