Fred Rogers' Neighbors: A Carnegie Mellon Story

CMU alumni share stories of their time on "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood"

Knitting Together: Rae Gold

Rae Gold removed the sleeves of the green sweater and tried to hand-knit them back together in order to correct the length of the arms, but the stitches would not properly align. A professional weaver and machine knitter for decades, this particular job was making her nervous.

This was Fred Rogers' sweater.

"Mister Rogers' Neighborhood," the educational children's television program produced in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, had approached Gold's machine knitters group looking for someone to appear in a segment about knitting. Gold volunteered.

After Gold's television debut, the production staff asked if she would be able to alter Rogers' green sweater. The sleeves were too long. She finally put the sweater on her knitting machine and made it look perfect again.

"I used to watch him all the time with my children. He was a very important part of our lives," Gold said. "I'm really sorry that there aren't more Mister Rogers around. We could sure use them."

Fred Rogers hosted many Carnegie Mellon University alumni over the years. Here are some of their stories.

On Saturday mornings, she would take a bus from Weirton to downtown Pittsburgh, and from there a trolley — not a make-believe one — to Carnegie Tech to attend design classes for high school students. After graduating from high school, she was not initially accepted into Carnegie Tech, but transferred in 1962. She graduated in 1966 with a bachelor's degree in graphic design. She stayed in Pittsburgh and made a living with her knitting machine, which ultimately led to her "Neighborhood" appearance.

Today, hundreds of Carnegie Mellon students walk past WQED's Fred Rogers Studio on their way to class, perhaps unaware of the impact that place had on millions of American children. The documentary "Won't You Be My Neighbor" and the Tom Hanks film, "A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood," filmed on location in Pittsburgh, have generated renewed interest in the life and work of Rogers. As real-life neighbors to the production, more than two dozen Carnegie Mellon alumni helped give life to Rogers' mission, including Gold.

Healing Waters: Francois Clemmons

At the Third Presbyterian Church in Pittsburgh on Good Friday in 1968, CMU graduate student Francois Clemmons sang out African American spirituals to the delight of the crowd. After the performance, a line of attendees formed to greet Clemmons. Very last in line stood a raincoat-clad Rogers, who stayed to tell Clemmons he had been deeply moved by his singing. That meeting was the start of a lifelong friendship that would set Clemmons on the path to healing.

Clemmons attended graduate school for music at CMU from 1967 to 1969. He remembers his time fondly, studying under Lee Cass, a professor of voice, who had encouraged him to include spirituals in his musical program.

"I began to feel like something very special was happening when I was singing, especially when I sang spirituals. I noticed that Lee Cass, along with many other fine musicians and colleagues, were not critical or judging me negatively when I performed. I remarked to Lee, 'Sir, you don't seem like my teacher anymore,'" Clemmons said. "I said, 'Lee, don't you have anything to say?' He said, 'yeah, sing another one!'"

In 1968, Clemmons won the Metropolitan Opera Auditions in Pittsburgh. He sang for seven seasons in New York City at Lincoln Center with the Metropolitan Opera Studio and in 1976 he won a Grammy Award for a recording of "Porgy and Bess."

After his performance at Third Presbyterian, Rogers asked Clemmons to join his television program.

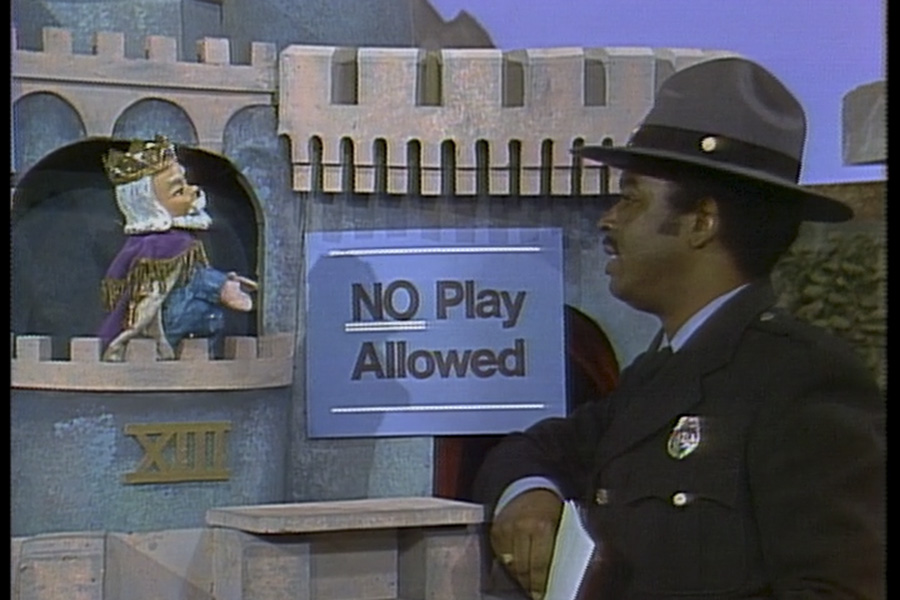

Francois Clemmons, in character as Officer Clemmons, speaks to King Friday the XIII on "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood."

Clemmons, who graduated with a Master of Fine Arts Degree in 1967, became known for his 25-year tenure as Officer Clemmons on "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood." Rogers took a personal interest in Clemmons, who grew up a child of poverty, neglect and abuse.

"Fred convinced me to go into therapy," Clemmons said. "I think he felt, if he loved me enough, he could heal me. I went into therapy for about five years at his suggestion. Best thing that ever happened to me."

With time, Clemmons both came to accept what had happened during his childhood, and that he was gay. He saw Rogers as the personification of unconditional love.

"He said he loves me just the way I am," Clemmons said. "I had never been told by anybody that they loved me. Isn't that interesting? To live a life always on the outside. Always wanting to belong. But knowing that because you're gay you're on the outside. And now I know that is not true! Because Fred Rogers said it wasn't true. It meant the world to me."

In 1969, Rogers invited Officer Clemmons to join him in soaking his feet in a children's pool in an episode. The image of a white and black man sitting together in a pool was a visual metaphor decrying segregated pools around the country.

"I remember looking at that, the one where I was in the pool. I thought what? In the kiddie pool? What in the world is this?" Clemmons said.

But Clemmons had come, with time, to trust Rogers' judgment. The scene became iconic. At the episode's end, Rogers shared his towel with Clemmons to dry his feet.

"I've been asked about that scene a thousand times since the show's end. The spiritual message and the impact of unconditional love, which Fred practiced daily, is powerful! Fred had a gift. That's all there is to it. His unique way of communicating with children was extraordinary."

Carrying on the Legacy: Hedda Sharapan

Hedda Sharapan's family didn't own a television until she was 10 years old. She fell in love with children's programs and Saturday morning cowboy movies. She pretended to have her own program, which she called "The Happy Hedda Show."

Sharapan grew up in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, and graduated with a degree in psychology from Carnegie Tech in 1965. While waiting to hear back from grad schools, she reached out to many companies after graduation for work. On a lark, she added WQED to her search. There was no position. "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" didn't exist yet, but she was encouraged to meet with Rogers, whose name she knew from a local children's program he co-produced in the 1950s.

Rogers suggested that she pursue a master's degree in child development at the University of Pittsburgh, where Rogers himself was learning about communicating with children. She followed his advice, and during her second year of grad school, Rogers secured funding to create "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood." He asked Sharapan to help with the program's production.

Sharapan was an unpaid member of what started as a black and white television experiment. They taped at night to accommodate the schedule of Johnny Costa, another Carnegie Tech alumnus who was the music director at KDKA by day and became the program's pianist and music director.

Within several months, she became a paid crew member. Sharapan performed various roles as the show grew: assistant director, assistant producer, associate producer. After her own child was born, she helped Rogers with his responses to the 15-30 letters he received daily from his viewers.

"It was important to him to answer every letter," she said.

When Rogers started receiving conference speaking requests — he was tied to production and couldn't attend — he offered to have Sharapan go in his place. She began to provide presentations, mostly professional development keynotes and workshops for early childhood teachers across the country in the early 1970s, work that she still continues as a highly popular speaker.

"Fred was translating child development into television, and I was helping to translate it back into child development," Sharapan said.

While Rogers voiced and manipulated most of his puppets, he sometimes needed extra hands for scenes with multiple puppets. Rogers introduced a set of characters called the Frogg Family to his Neighborhood of Make Believe, and Sharapan voiced Mrs. Frogg.

"He would do this from time to time. He would just ask somebody, 'would you help with this?'" Sharapan said. "I will tell you that is the hardest work I ever did."

Sharapan would stoop behind the set with her arm held high inside of Mrs. Frogg. Unable to put her arm down, it would start to numb. Taped to the back of the set would be a script with her lines marked, and a 3-inch television monitor showed her how the scene looked. Actions in the monitor were mirrored, so moving the puppet to the left made it move right onscreen.

"Fred was a brilliant puppeteer," Sharapan said. "They were simple hand puppets. Most of the time he had one puppet on each hand, and they each had different voices. It was a delight to be part of the actual production instead of watching it happen. I was really honored he would trust me with something like that."

Sharapan became the director of Early Childhood Initiatives for the company, and continues to work as a script consultant for the popular "Daniel Tiger's Neighborhood," an Emmy-winning animated children's program created by Fred Rogers Productions that continues Rogers' legacy. For her work over the years, she was named a Senior Fellow at the Fred Rogers Center and received an honorary doctorate from St. Vincent College where the center is located.

"There was a time when we weren't sure how people connected with Fred," Sharapan said. "People recognize (now) that what he was doing was something important. That children matter. That they need adults in their lives who can help them navigate the world and understand who they are."

Harmonizing with Rogers: Joe Negri

Handyman Joe Negri describes himself as the most un-handy man in the world. Rogers didn't care. He was a master of pretend, so Negri played a handyman for over 35 years on "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood."

Before all that, Negri had been discharged from the Army, came back from Europe and was figuring out his next move while playing guitar at house parties in Pittsburgh with Costa, who was then a senior at Carnegie Tech.

Costa encouraged Negri to enroll at Carnegie Tech as a music composition major, since they didn't take guitar students. Negri wrote a melody for composition teacher Nikolai Lopatnikoff that he has kept to this day. Lopatnikoff accepted him into the School of Music program in 1950.

"I had been in show business since I was a child. I had entertained on the radio, on all kinds of programs and children's shows. But I wasn't very good at expressing myself," Negri said. "That first year, there was an English course called 'Thought and Expression.' Early in the semester, they asked us to write something about ourselves. I'm trying to explain how I have difficulty in expressing myself, and the professor gives me it back with a C- and says, 'You did a very good job of explaining how you can't express yourself.'"

Carnegie Tech taught Negri music theory, counterpoint and composition. He wrote numerous musical pieces, and did learn how to express himself.

Negri met Rogers in the late 1950s while working as the musical director for Channel 4, WTAE-TV. Rogers had a 15-minute show on the station similar in format to what "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" would become. Negri provided musical background for the show.

Joe Negri sings with Lady Elaine Fairchilde on "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood."

"One day Fred said to me, 'Joe, why don't you do a walk around the neighborhood and just talk to some of the puppets?'" Negri said. "So, I did. I'm talking to Corney [Cornflake S. Pecially] and I'm talking to X the Owl and I'm talking to King Friday. And little by little, he's asking me to do it more regularly."

When Rogers landed at WQED, he called Negri and asked him to become a show regular.

"It was always beautiful. I think it was the music that kept us close," Negri said. "And Johnny Costa was there making gags and keeping everybody happy with his silly stuff. He was such a talent but he was cuckoo, too."

On "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood," Negri performed with musical greats like Yo-Yo Ma and Wynton Marsalis. He appreciated the creative freedom Rogers allowed with the show's music. When he or Costa would enrich a song by adding a harmonization, Rogers never complained. He'd just use Negri's supplementations.

"The songs are terrific. Fred didn't write one song that's bad," Negri said.

Television Magic: Dan Kamin

"I never knew this was in color!" Dan Kamin said while watching footage of his 1974 appearance on Rogers' program. Kamin hadn't seen the clip since it was shot some 45 years ago.

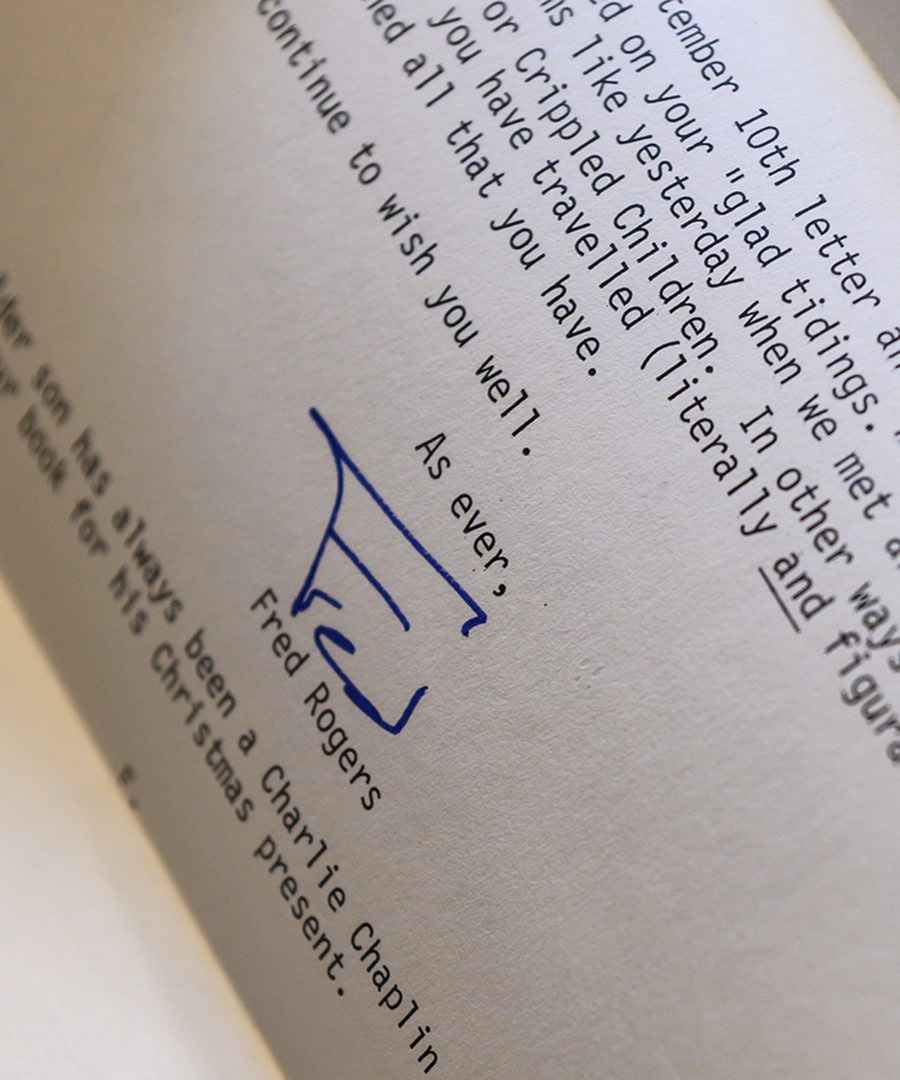

His home office in Mt. Lebanon, Pennsylvania, brims with books about Charlie Chaplin, including several written by Kamin himself, along with some souvenirs of his time with Rogers.

Kamin believes that film is the central art form of the 20th and, thus far, 21st century, and it has had a powerful influence on his life. A biographical movie about Harry Houdini that Kamin saw when he was 8 or 9 inspired his fascination with magic. Years later, a film series hosted by Carnegie Tech's Film Art Society exposed him to Chaplin. He describes that film as, "the best work of art I had ever experienced."

While no one was making silent films anymore, a man on CMU's campus was keeping the tradition of silent storytelling alive. Jewel Walker was a world-class mime artist who learned his craft from the man who trained the celebrated Marcel Marceau. Kamin basically hounded his way into Walker's classes in the drama Department, and their master-disciple relationship continued until Kamin graduated from the College of Fine Arts in 1968.

One of Kamin's fellow students knew Rogers and arranged an introduction in the hopes that it could lead to a job. Rogers had just begun his program. Kamin sat across from Rogers and David Newell, who played Mr. McFeely, the speedy deliveryman, in a cafeteria. Kamin remembers that the faces of Rogers and Newell were tinted orange from their heavy pancake television makeup, a necessity in the early years of television.

Rogers connected Kamin with an organization that later became The Children's Institute, which serves children with disabilities. As a staffer, Kamin created graphic materials for speech therapy, as well as mounting plays and making movies with the children.

Some of his first mime shows were for the children there, as well as the community of hospitals and rehabilitation centers in the Pittsburgh region. At the same time, "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" went national.

Several years passed without any contact between Kamin and Rogers. Then the Sixth Presbyterian Church of Pittsburgh asked Kamin if he could create a sermon in mime. Though he had some trepidation about the audience's reaction, he created a comic piece using mime technique retelling the story of creation. The usually somber church-goers laughed uproariously. Among them were Rogers and his wife, Joanne.

The couple sent Kamin a letter in the mail complimenting him on the performance. Shortly after, Kamin was invited to appear on "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" as Master Mister Magic Maker. He worked with Rogers and his writing team to integrate his magic into the program's storyline.

"It was one of the most collaborative pieces of film work I've done," Kamin said. "He was such a receptive person. His staff was so attuned. It was like walking into a well-oiled machine."

Dan Kamin, left, appears on "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" with Fred Rogers, center, and David Newell.

Years later, Rogers asked Kamin to revisit the Neighborhood of Make Believe, this time as a mime. "He called me, 'K-Man.' I loved that!"

Kamin, who performs internationally and has been involved in the production of major movies, still thinks back to discovering the power of mime at CMU. "I was majoring in industrial design, but Carnegie Mellon was a cauldron of creative possibilities," Kamin said. "Who would have thought that a student-run film series, along with a gifted professor who couldn't resist the enthusiasm of a student, would change the course of my life?"

A Mother's Tale: Holly Dobkin

Holly Dobkin only applied to Carnegie Tech. Her mother, Audrey Roth, was an alumna. Dobkin was accepted as a drama major and attended from 1966-1968.

Dobkin worked in makeup and wardrobe on "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" during the program's first season produced in color. Cameras in that day and age required their subjects wear makeup to look normal, and she applied Rogers' makeup daily.

The program was shot in segments. Dobkin kept track of what Rogers wore and where things were placed in each segment.

"Every little thing that we saw, there was a reason for it," Dobkin said. "There was something to help a child deal with whatever we all take for granted as an adult. Fred talked to children not as adults, because they're not adults, but he gave them the same respect as he would adults. And most people don't do that with children."

During Dobkin's time with "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood," she was struck by Rogers' careful consideration for every element of production.

"There was nothing left to chance, nothing taken for granted," Dobkin said. "Every word was carefully curated. Fred would stop tape if somebody used a word that he didn't feel conveyed the exact meaning that he wanted to convey."

Fred Rogers, left, speaks to Holly Dobkin, far right, Dobkin's mother Audrey Roth and Dobkin's daughter Maggie Dobkin during a segment. Holly Dobkin and Audrey Roth both attended Carnegie Tech, and Maggie Dobkin would graduate from Carnegie Mellon in 1992.

Dobkin's mother, who died in 2016, became a regular, playing Miss Paulificate in the Neighborhood of Make-Believe and Audrey Cleans Everything in the real Neighborhood.

On a car ride home, Dobkin remembers speaking to one of her daughters about work and what her grandmother did. This was the first time she spoke to her young daughter about the subject, and expected her little one to light up about her grandmother being a television star.

Dobkin asked little Anna what she had told her classmates about her grandmother's job.

Anna responded, "My grandma's a cleaning lady!"

That's how real "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" was to little Anna. Dobkin couldn't wait to go home and tell Rogers.

He loved it.

The second version of the iconic pool scene served as a farewell to Clemmons from the program.

The second version of the iconic pool scene served as a farewell to Clemmons from the program.

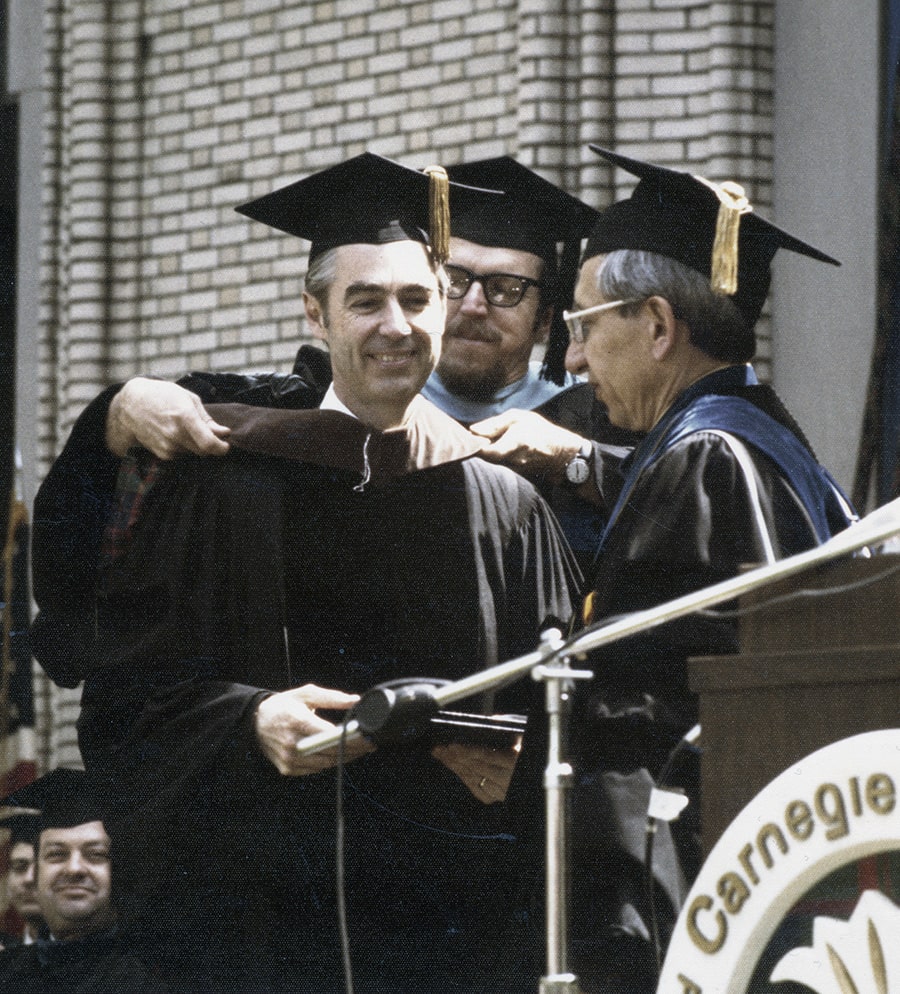

Carnegie Mellon University awarded Fred Rogers an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts in 1976.

Carnegie Mellon University awarded Fred Rogers an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts in 1976.