Article: Efforts to Memorialize World Trade Center Victims

CHRS Director Jay Aronson Assesses On-going Efforts to Memorialize World Trade Center Victims 15 Years After the Attacks in the New York Daily News

Today, the 15th anniversary of the September 11 terrorist attacks, is a good time to pause to ask whether redevelopment efforts at the World Trade Center and the 9/11 memorial and museum have facilitated healing and honored the victims. One would be hard pressed to answer this question with an unqualified yes.

While life has undoubtedly returned to the site, the dead still cast a long shadow there.

Human societies have been recovering from conflict and disaster, and memorializing the dead, for millennia. Yet we still argue about what communities, nations, families of victims and ordinary people need to begin to put their lives back together. This suggests that rebuilding and mourning in the wake of tragedy are dependent upon culture and the peculiarities of history. But history also tells us that the process matters as much, if not more, than the outcome.

At least by this measure, New York's recovery from the Sept. 11 attacks has been deeply problematic. Controversy and rancorous disputes over money and control have accompanied nearly every decision made concerning the World Trade Center site and the way we remember the victims.

Could this discord have been avoided, or at least mitigated?

My research on the recovery, identification and memorialization of the victims of the World Trade Center attacks suggests that while some degree of controversy is inevitable when dealing with such complicated and emotionally fraught issues — especially when rebuilding involves a web of individuals and complex bureaucracies — a good deal of the fighting, inefficiency and embarrassment could have been avoided if politicians, developers and others had been even slightly more focused on the dignity of survivors, families of victims and community members in their quest to get what they wanted.

Instead, power, money and ego played an outsized role in the struggle to rebuild. New York and national media picked up on this story and put it on display for the world to see.

From the very beginning, it was clear that the office space that had recently been leased by developer Larry Silverstein from the Port Authority and the retail space controlled by Westfield Corporation would be rebuilt. The initial demands of many families, echoed by then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani, for the site be turned into a 16-acre memorial eventually led to a compromise in which half the site would be given over to a memorial and the other half would serve commercial and other uses.

The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, a public entity created and controlled by the state, became the lead agency in redeveloping the World Trade Center site and would serve as the recipient of the billions of dollars in aid earmarked by the federal government to respond to the attacks.

Given the close links of LMDC officials to Gov. George Pataki and Mayor Michael Bloomberg, it is perhaps unsurprising that a major goal of the organization was to promote economic development of the area and prevent business from decamping to Connecticut, New Jersey and elsewhere.

This meant that while families, local residents, academics, the urban planning community and the general public could demand all they wanted at the site, economic needs would be prioritized. It also meant that redevelopment would be intensely political and subject to the same kinds of cost overruns and institutional jostling that tend to accompany government action.

Power struggles between the LMDC, the Port Authority, and Silverstein over control of the site, the acrimony between eventual site plan completion winner Daniel Libeskind and other stakeholders (especially Silverstein's favored architect David Childs), disputes over Michael Arad's memorial design, battles over the placement of the International Freedom Center and other cultural institutions in the memorial quadrant — not to mention the outrageous costs associated with fixing the transportation infrastructure and putting up buildings at the site — have been well documented in this newspaper, in other media accounts, and in several books.

My own research has documented debates about storage of human remains at Fresh Kills Landfill and in the city's Office of Chief Medical Examiner repository in the memorial and museum complex, and the challenge of determining the placement of names on the memorial parapets. Further, disputes over money and management of the construction of the memorial and museum complex lent credence to many families' fears that their needs and desires were irrelevant in a larger political and economic fight. It also soured their views of the complex and reduced its potential to facilitate rebuilding and regeneration of families and communities.

I am often asked to assess the extent to which the existing memorial and museum have facilitated healing among families and the general public. While it will take rigorous research to give to a definitive answer, I have reached a few conclusions already during the course of my research.

Families, survivors and the city would have benefited from a longer period between the event and efforts to memorialize it. It is hard to know in the heat of the moment what memorial forms will have lasting meaning as memory of the event and its victims fade. The rawness of emotion and grief, as well as the multitude of competing interests at play, made it very difficult for stakeholders to compromise with one another and agree on a shared vision of what the memorial ought to be and do.

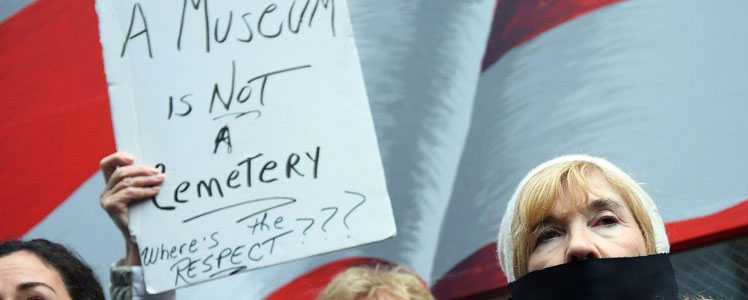

Families, survivors and ordinary citizens were not well managed by the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation or city officials in the sense that they were given a public voice, especially through community forums, but not necessarily listened to. Power was often vested in a small cadre of family members who were more likely to go along with the wishes of decision makers. Those left outside the circle of power had to resort to increasingly reactive and publicity-seeking measures to have their voices heard on issues such as memorial design and the internment of unclaimed and unidentified remains.

While their tactics were not always productive, the central issues underlying their demands were generally legitimate — and decision makers sometimes listened to them when doing so did not interfere with their larger plans.

In the future, planners and politicians should either give the public more genuine power in decision-making or be more honest about the impact of democratic deliberation.

It is unclear whether the museum and memorial create the kinds of contemplative spaces that families wanted and foundation and city officials claimed to be creating. During my visits to the complex, the memorial has had the feeling of a tourist attraction rather than a place to mourn the dead and reflect on the fragility and beauty of life.

The museum affiliated with the memorial is well-designed, and creates an incredibly intense and moving experience. Still, it is not clear whether the price tag, plus all of the associated security and maintenance expenses, was worth it, or whether the same goals could have been accomplished more economically, possibly in another location.

Many commentators have also called the $24 entry fee troubling, particularly because the museum has at its core a public service mission: to teach the public about 9/11 and the people who died that day.

A more positive legacy of the response to the tragedy of 9/11 has been the work of the New York City Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. The World Trade Center attacks occurred at the precise moment in history when large-scale identification of fragmented and damaged human remains was becoming not just theoretically possible, but doable. Academic researchers and private companies had created technologies that enabled rapid extraction and analysis of genetic material from biological specimens. At the same time, scientists and activists involved in the investigations of mass atrocities were developing methods to apply these tools to the damaged and degraded forensic specimens recovered from complex graves.

These advances emboldened New York City's medical examiner, Charles Hirsch, to promise families his staff would seek not just to identify all victims of the attacks, but rather identify and return every human body part recovered from the site. This promise would have long-lasting consequences — most notably because it meant that the OCME would never complete its investigation so long as there were still unidentified remains and forensic science continued to progress.

As a result, unlike previous tragedies in which unidentified and unclaimed remains were buried in common graves, OCME would have to maintain a repository of remains that could be accessed for future testing.

Thus far, well over $80 million has been spent on this effort. The primary goal has been to link even the smallest human remain to a person in an effort to provide proof of death and the most complete body possible for families. The unprecedented forensic effort was also meant to signal to the world that Americans were dramatically different from the terrorists, who seemed not to value human life. It was as much a political and moral statement as it was a scientific and legal one.

Hirsh's promise to families to continue to identify victims meant that remains had to be stored somewhere in perpetuity. Given the desire of most family groups that emerged after 9/11 for the remains to be stored where their loved ones died, that location became the space shared with the memorial museum.

This situation has the incongruity of simultaneously hiding them away and making them an element of the museum, which is something that angers a subset of families. It also may create a dilemma for families who have not received remains, because the museum becomes a de facto cemetery for them.

The possibility of identifying even the most damaged remains means that we may be less prone to forget them and the victims to whom they belong. But sometimes it is easier for families and communities to get on with life if the dead can eventually recede from view.

We of course do not forget the dead, but most societies have rituals and practices that help families put the dead to rest and reassert ties among the living. And while we should never put a "statute of limitations" on mourning or grief, we ought to take seriously the implications of identification and potential problems of identification efforts without end.

Whatever the case, the response to the 9/11 World Trade Center attack tells us something about American culture: We seem to fear erasure from history and memory, and find the thought of unidentified remains unnerving. Science and technology work against this erasure and lack of identity, which is a consolation in what the news constantly reminds us is a dangerous and uncertain world.

Aronson is an associate professor of science, technology and society at Carnegie Mellon University and the author of "Who Owns the Dead? The Science and Politics of Death at Ground Zero."