GAITAR@Scale 2

Impacts of Generative AI as a “Feedback Partner” on Students’ Writing (Spring 2025)

Research Question(s):

To what extent does substituting genAI for peers in a “peer feedback” exercise impact students’

- ability to use evidence to support a claim in their writing?

- self-efficacy regarding course learning objectives and self regulatory writing efficacy?

- perceptions of the writing process?

Study Participants:

424 students across 28 first-year writing courses taught by 16 instructors

- Condition 0: n = 103 students

- Condition 1: n = 97 students

- Condition 2: n = 105 students

- Condition 3: n = 120 students

Intervention & Study Design:

Within the first three weeks of the semester, all instructors implemented lesson plans and homework related to the skill of “making a claim and supporting it with evidence”. Instructors then assigned an 800-1000 word Comparative Genre Analysis (CGA) assignment leveraging this skill. After submitting first drafts, students engaged in a feedback and revision process - which varied across genAI treatment or no genAI control conditions, described below. Instructors did not provide feedback to students prior to the second draft. Then, without using genAI, all students revised a second draft for instructor feedback. Following this, students submitted a revised third (and final) draft for grading (10% of final course grades). Figure 1 highlights the study design and instructional sequence.

Figure 1. Study design and instructional sequence

Experimental Conditions:

In our quasi-experimental study, we assigned entire courses of students to one of four conditions (Table 1). For example, students in condition 0 engaged in a “typical” peer review process - giving and receiving feedback with two peers.

Table 1. Experimental Conditions

|

Feedback |

Condition |

Giving Feedback |

Receiving Feedback |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Human |

Condition 0 |

Peers - 2 sets of feedback |

Peers - 2 sets of feedback |

|

genAI |

Condition 1 |

Standardized Sample Papers - 2 sets of feedback |

genAI - 2 sets of feedback |

|

genAI |

Condition 2 |

— |

genAI - 2 sets of feedback |

|

genAI |

Condition 3 |

— |

genAI - 2 sets of feedback, 2 times |

Students assigned to a genAI condition (conditions 1, 2, and 3) used Copilot (i.e., Enterprise account in January 2025). These students used genAI (instead of a peer) as a feedback partner early in the revision stage of writing, prior to receiving instructor feedback on later drafts. Using scripted and researcher-validated prompts, students each uploaded the first draft of their paper and the evaluation rubric¹ to Copilot. Copilot provided two independent² sets of rubric-based feedback³ to inform students’ revisions.

We specifically designed condition 3 to test one of the obvious affordances of genAI tools—the ability to receive instantaneous feedback and redraft multiple times. Condition 3 students received the two sets of Copilot feedback (as in Condition 2) but then revised the first 1-2 paragraphs of their draft and submitted it to Copilot for two more sets of feedback.

Comparing Conditions 1 and 2 tests for the previously documented phenomenon of “givers’ gain” (Lundstrom & Baker, 2009), i.e., a reviewer's writing can benefit from reading and giving feedback on a peer’s writing. To our knowledge, this study is the first test for givers’ gain when the student is reviewing peer work and is also receiving feedback on their own writing from genAI.

¹Subject matter experts helped researchers create and then validate the rubric using prior students’ writing deliverables.

²Quality assurance testing revealed variation across multiple trials using the same prompts and student work, as is the case when receiving feedback from multiple peers.

³GenAI prompts constrained Copilot from generating revised or new text for students.

Data Sources:

- Students’ Comparative Genre Analysis (CGA) Papers, scored via a rubric to evaluate their ability to make claims supported by evidence. Students submitted two drafts and a final paper.

- Pre/post surveys of students’ self-efficacy regarding their writing ability and self regulatory writing efficacy (Modified Writing Self-Regulatory Efficacy Scale (Sanders-Reio, 2010))

- Post survey items of student perceptions and ratings of the feedback that they received.

Findings:

Research Question 1: To what extent does substituting genAI for peers in a “peer feedback” exercise impact students’ ability to use evidence to support a claim in their writing?

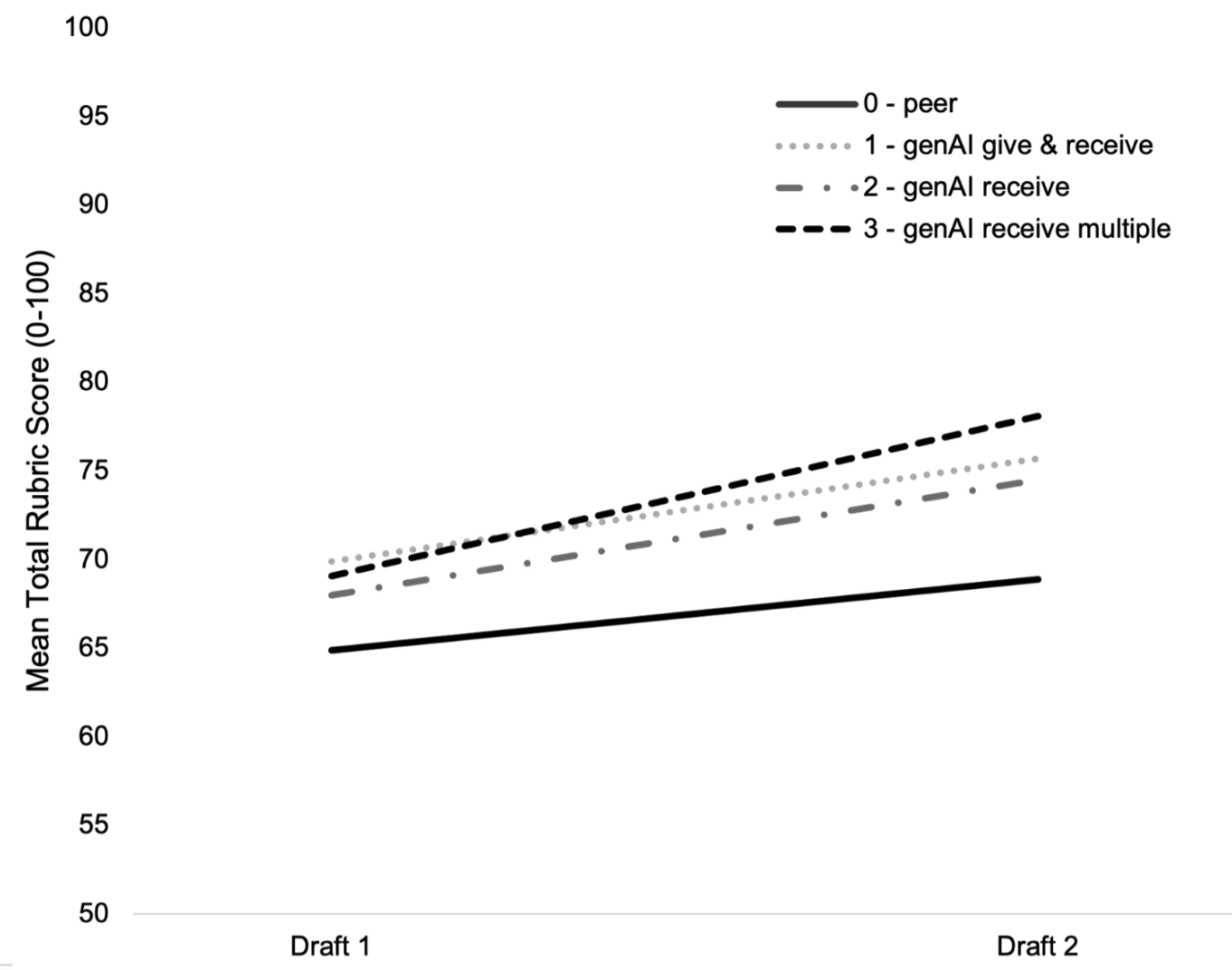

For all conditions the mean CGA rubric scores improved between drafts 1 and 2 after receiving and applying peer or genAI feedback. The only significant difference in the rate of improvement (i.e., learning) was between condition 0 (peer) and condition 3 (genAI - receive multiple).

Figure 2. Raw mean total rubric scores for CGA drafts 1 and 2 across conditions. Mixed level modeling indicated a marginally significant interaction of condition and time on mean rubric score (F(3,422.99) = 2.58, p = .05). Closer examination of the change in scores over time (i.e., learning) revealed that only condition 0 (peer) and condition 3 (genAI receive multiple) differed significantly (t(422.97) = 2.74, p = .01).

Research Question 2: To what extent does substituting genAI for peers in a “peer feedback” exercise impact students’ self-efficacy regarding course learning objectives and self regulatory writing efficacy?

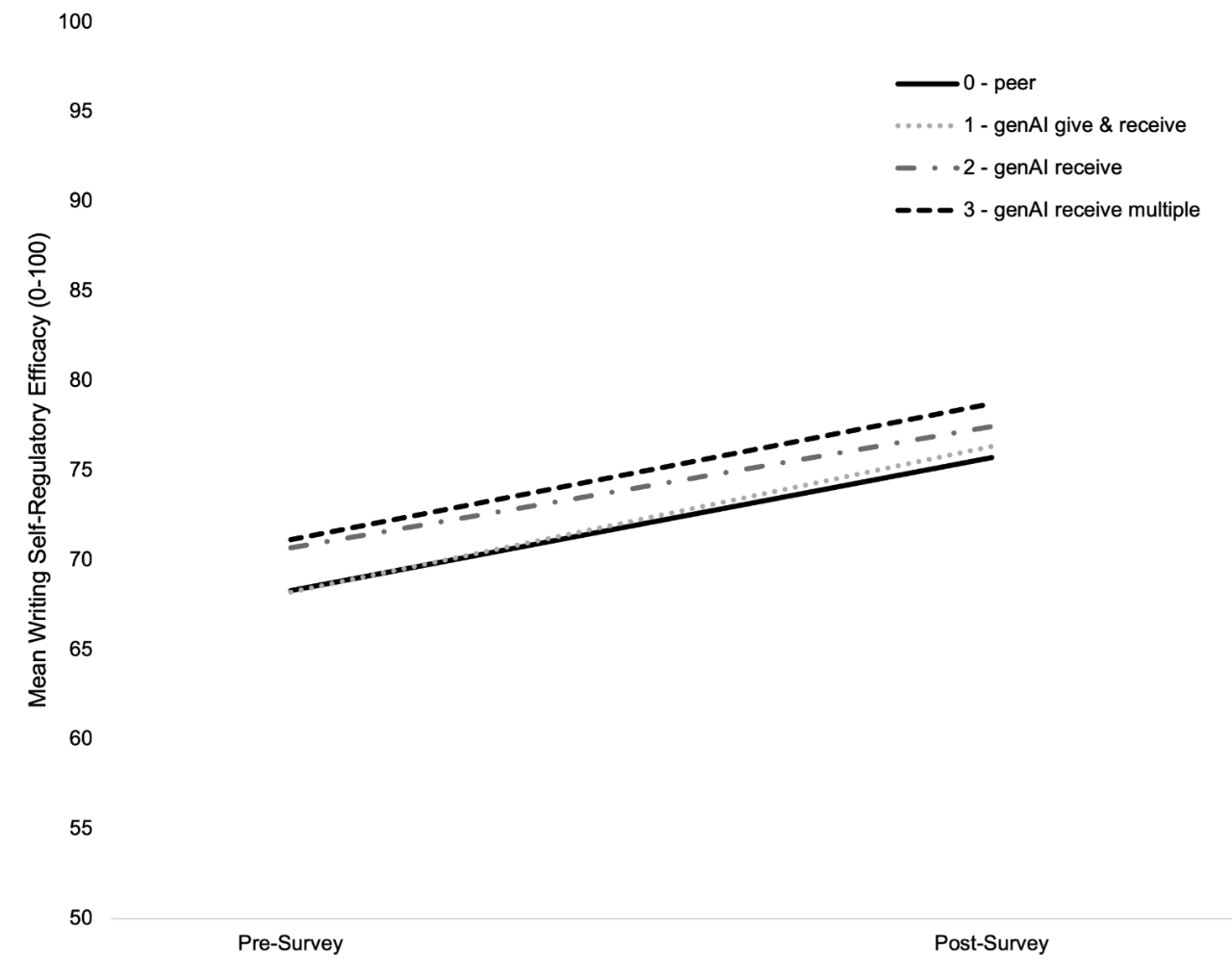

Although there was no difference between conditions, students’ self-efficacy for both the course learning objectives and writing self-regulatory efficacy significantly improved from pre to post (i.e., before draft 1 to after draft 2). Figure 3 highlights the writing self-regulatory efficacy outcome, and the course learning objective self-efficacy followed a similar pattern. Statistics for both outcomes can be found in the figure caption.

Figure 3. A two-way mixed ANOVA found no significant interaction between time and condition for students’ writing self-regulatory efficacy (F(3,284) = .13 p = .94). There was a significant main effect of time (pre/post gain) F(1,284) = 103.13, p < .001, ɳp2 = .27. **While the course learning objective self-efficacy is not pictured above, results are similar. There was no significant interaction between time and condition for course learning objective self-efficacy (F(3,284) = .48, p = .70). There was a significant main effect of time F(1,284) = 36.86, p < .001, ɳp2 = .12.

Students in all conditions provided favorable ratings for the perceived quality of feedback that they received. However, when comparing students in all genAI conditions vs. students who worked with a peer for feedback, students receiving peer feedback rated the feedback as more useful on several measures (Table 2). Not only did students in the peer condition rate their feedback as being of a higher quality, they also on average reported incorporating more of the feedback (about 70%) into their revised draft 2 as compared to their peers receiving genAI feedback, who incorporated about 63% of the genAI suggestions into their second draft. Furthermore, more students found that peer feedback was useful in part because it allowed them to see how other readers would interpret their work than did students who received genAI feedback.

Table 2. Measures of the perceived usefulness of feedback received by condition (peer vs. genAI feedback).

|

Perceived Usefulness |

Statistical Test |

|

|

Quality of feedback - defined as actionable, specific, prioritized, balanced, and appropriate volume |

Peer > genAI |

t(314) = -2.09, p = .02, d = -.25 |

|

Ability to perspective take - feedback was helpful because it allowed the author to understand how it was received by a reader or future audience* |

Peer > genAI |

Z = -4.08, p < .001 |

|

Percentage of feedback incorporated - feedback was helpful to the point that the author ultimately incorporated it into their revisions |

Peer > genAI |

t(314) = -2.53, p = .01, d = -.30 |

*Chi-squared test was used

Eberly Center’s Takeaways (*adapted from submitted manuscript):

Research Question 1 and Research Question 2: Results suggest that with careful prompt engineering and quality assurance testing (we spent many hours on this step), genAI may be a viable alternative to peer feedback without compromising students’ learning (although our perceptions data shows that students value peer feedback). In this study, multiple rounds of revision and genAI feedback resulted in higher performance than peer review regarding students’ ability to make a written claim supported with evidence. We hypothesize that the mechanism behind these results is the fact that genAI provides “just in time” feedback and the opportunity for more revision cycles (i.e., practice and feedback). This “anytime, anywhere feedback” is an affordance of the genAI tool that’s not possible in traditional peer-to-peer feedback interactions. However, additional research is needed to investigate this claim.

Results reinforce some of the previous literature on feedback and writing instruction. Draft 2 increased in quality (as compared to draft 1), highlighting the importance of providing students time for feedback and revision (Bean & Melzer, 2021). The fact that all conditions saw equally significant increases in self-efficacy suggests that it is the carefully scaffolded revision exercise (rather than the different experimental conditions) that provide students with increased confidence in their writing skills.

Beyond receiving feedback, our data do not show any added benefit to providing feedback. The lack of a difference between condition 1 (genAI giving and receiving feedback) and 2 (genAI receiving feedback only) suggests that the “giver’s gain” (Lundstrom & Baker, 2009) was not present.

Research Question 3: While students in all conditions found the feedback that they received to be useful, students appear to especially value the human element of the peer feedback. We hypothesize that instructors assigning a round of peer review followed by a round of carefully scaffolded genAI feedback may optimize learning outcomes and the student experience. This approach would leverage both the perceived benefits of peer feedback and affordances unique to genAI (instantaneous repeated feedback anytime, anywhere). Our study did not include this feedback combination, so we hope future research will test this prediction.

References

Bean & Melzer (2021). Engaging ideas: The professor’s guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom, 3rd edition. Jossey Bass.

Lundstrom K. & Baker, W. (2009). To give is better than to receive: The benefits of peer review to the reviewer's own writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 18(1), 30-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2008.06.002

Sanders-Reio, J. (2010). Investigation of the relations between domain-specific beliefs about writing, writing self-efficacy, writing apprehension, and writing performance in undergraduates. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. College Park: University of Maryland.