She's on a Roll

The history of women in Buggy

By Katy Rank Lev

Spring 2020 will mark the 100th year Buggies roll through Carnegie Mellon University, a tradition where student groups build vehicles to race around the twisting hillsides of the Pittsburgh campus.

For many years, Buggy — or Sweepstakes as it is formally known — was organized by and for male competitors, but the story of Sweepstakes has a rich history of women's leadership and involvement. They have been pushers, drivers, mechanics and designers, shaping Buggy's notoriety.

The first documented female driver, according to the records of Buggy Historian Tom Wood, took the wheel in 1973, driving for Kappa Sigma Little Sisters in an exhibition heat against Phi Kappa Theta. Mary K. Skriba (DC1974) slotted a time of 5:07.5 and kicked off a long tradition of women behind the wheel, especially as buggies grew smaller and more aerodynamic.

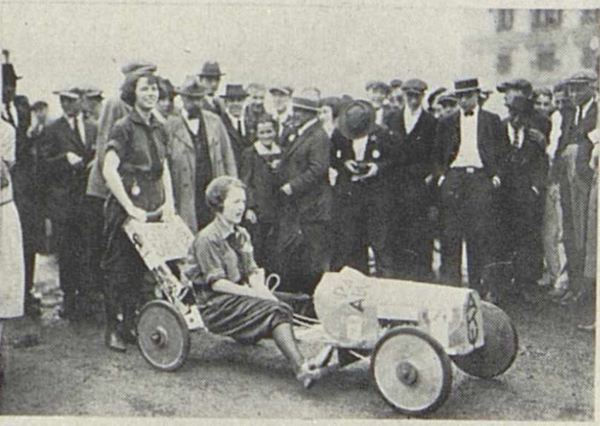

Women take the Buggy wheel: Alpha Kappa Psi sorority entered a buggy in an exhibition heat in 1922.

By 1981, most student groups were recruiting women to drive and team CIA boasted the first female driver in the winner's circle — Chari Heim (A 1983). No male driver has won since.

But women aren't just behind the controls of the flying carbon fiber. Joan Roman Bothwell (A 1978) became the first woman to chair the Sweepstakes Committee in 1976. Legend has it, nobody else wanted the job and Bothwell volunteered to keep the tradition alive.

Anne Witchner (DC 1973), currently associate dean of Student Affairs, was the Sweepstakes advisor for more than 20 years. She said committee work is thankless and requires maturity to guide competitive, high-achieving student groups through strict safety rules for Buggy.

Witchner knew the student organizers had difficult work in the months leading up to Buggy — they had to obtain permits for road closures, communicate with the police, campus community and local neighbors, as well as bear the brunt of frustration when a student organization was told no.

Witchner said, "Ideal students for the leadership roles required nascent leadership abilities and maturity to successfully fulfill their roles. It is a lot to ask of any 19 – 23-year-old! But whenever we had a strong female chair, she gained such respect."

Janice Golenbock Schneekloth (CS 2001, 2003) held that role in 2003 after driving for five years. "Nobody wanted to run Sweepstakes. Frankly, you're making difficult decisions that have the potential to upset people," Schneekloth said, remembering having to disqualify teams for rule infractions. "That was really painful after watching them work so hard all year," she said. "But I loved Buggy and it was such a good opportunity for me to stretch those organizational muscles as a leader."

Schneekloth notes that each chair gets to leave their mark on the tradition, getting a chance to try out ideas that sometimes fail (she tried to move the Design competition from the gym into the Cohon University Center for more foot traffic and realized there was less space and too much chaos).

But the chair also feels the pride when things go well. During Schneekloth's time at CMU, Buggy reached gender parity for push teams. "Watching the progression of these small changes to make Buggy more inclusive has been important," she said.

"There's no buggy without women." — Jessica Thurston

Like many women of slight stature, Thurston was recruited as a driver on her first day of orientation. She drove for team Fringe for four years before taking the role of chair of the Sweepstakes Committee during graduate school, then returning as Head Judge.

Approximately half of the committee leadership roles have been held by women in the years since Bothwell first grabbed the clipboard. Thurston says the experience has had a lasting impact on her career path.

"I like to be in charge. I own that about myself," she said. Thurston now leads environmental, social and government strategy at ViacomCBS, a position where she is still looking over vast systems and seeing how all the parts fit together.

Trish DiMarco Ng (A 1989) also found her work with Buggy to be valuable for her career path. Ng became the first female safety chair in 1989, 10 years after women's push teams were officially invited to compete in Buggy. She was a small woman in stature, and her older brother initially tried to recruit her to be a driver. "I wasn't that small," Ng said. While she didn't fit inside the Buggy, she did want to get involved, and the safety chair role clicked with her. "I guess Buggy helped me get used to being the only woman in the room," Ng said.

"I just remember going into nasty garages and basements of fraternity houses enforcing rules. We had to inspect every buggy before every milestone," said Ng. "I don't even know how we did that without cell phones and email."

Ng often felt intimidated, but she stood her ground and looked to the indefatigable support of Witchner. Ng had already served as a residential advisor and had communication and conflict resolution skills from that role. When Witchner recruited Ng for a Sweepstakes committee role, she knew she could rely on the work study student who had a knack for multitasking and attention to detail.

Ng was recently interviewed about her work in the athletic shoe industry, another space that's been dominated by men. "For most of my career, I was the only woman at design and product development meetings or factory visits," Ng said. "It was helpful to be comfortable in that situation."

Thurston has often felt that way about her experiences in corporate America.

She rounded out her Buggy experience after graduation as the first female commentator for the event in 2012, a role that let her "geek out and discuss what I knew about the differences between the teams, their challenges and their opportunities."

For many teams, the biggest opportunity in Buggy is the institutional knowledge that comes from each organization's alumni having constructed a vehicle and competed in the races for the better part of a century. Even though female push teams have been on the rolls schedule since 1979, these groups competed in borrowed buggies.

That all changed in 2004 when Jaci Feinstein (E 2006) served as head mechanic for the Kappa team that competed as the first all-women's team. That year, Kappa's sisters constructed a buggy from scratch, but weren't able to complete it in time to compete. So the team borrowed a metal frame and shell from another organization to get Ursula started.

"We had no historical knowledge," Finstein said. "A lot of the groups had 80 years of notes and alumni telling them how to do things. We were researching how to make molds and learning about ball bearings."

Finstein says the buggy they made didn't look good and it didn't go fast, but it rolled over the finish line completely powered by women — drivers, pushers, mechanics and team administrators.

Finstein is looking forward to the historic 2020 Buggy competition. "Buggy is an amazing opportunity for students to work on teams, to accomplish something together," she said.

And at every step along the way, women have helped to build this uniquely CMU custom of camaraderie and competition. "Women have been mechanics, been behind the scenes strategizing. We've helped shape this tradition," Finstein said.

Key Milestones for Women in Buggy

The first official women's heats took place in the 1979 Sweepstakes.

The first official women's heats took place in the 1979 Sweepstakes.

1922: Sorority Alpha Kappa Psi pushes a buggy in an exhibition heat

1972: Kappa Sigma Little Sisters run an exhibition heat against Phi Kappa Theta and Pi Kappa Alpha Alumni

1973: first documented race with a female driver, Mary K. Skriba clocks a time of 5:07.5 in the Kappa Sigma Little Sisters exhibition heat against Phi Kappa Theta and Pi Kappa Alpha Alumni.

1976: first female chair of Sweepstakes Committee, Joan Bothwell

1979: first official women's heats added

1981: first female driver in the winner's circle, Chari Heim; vice chair of Sweepstakes Committee role created; first time women hold both chair and vice chair positions (May Slava Taylor and Sheila Dunham)

1988: first female safety chair, Tricia DiMarco

1998: first female head judge, Fiona Bedford

2003: first entirely female Sweepstakes Committee, Janice Golenbock, Carla Geisser, Brooke Abounader

2004: first all-women's team to enter, Kappa Kappa Gamma

2011: first on-screen female commentator, Jessica Thurston

The preceding story demonstrates CMU's work toward attaining Global Goal 5.