A New Way To Learn About Learning

Aliens, video games and brain patterns provide insights into adult learning

As a baby listens to her parents talk, her brain somehow sorts the sounds into specific sound categories. This happens even though mom and dad say the word "hello," slightly differently because of accents or pitch. Despite those subtle differences, a baby's brain absorbs the sounds and classifies them as equivalent.

This kind of learning is quite different from the way researchers study adults learning a second language. Foreign language learning is often studied in a controlled setting through trial and error or multiple-choice options with reward-based results.

A team of Carnegie Mellon University researchers, together with the University of Pittsburgh, has developed a unique way to learn more about how adults use their brains to learn in a complex environment. They created a video game filled with aliens and strange sounds, then sent study participants into an MRI machine to play.

A team of Carnegie Mellon University researchers, together with the University of Pittsburgh, has developed a unique way to learn more about how adults use their brains to learn in a complex environment. They created a video game filled with aliens and strange sounds, then sent study participants into an MRI machine to play. The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

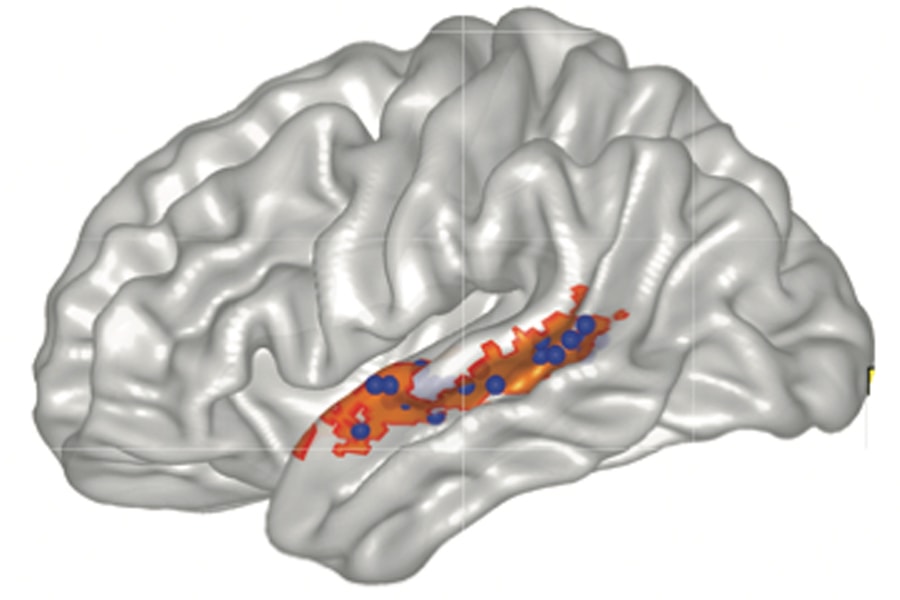

By watching the participants' brain activity, the researchers noticed that a certain learning section of the brain, the striatum, was very active among those players when each alien made sounds with a consistent underlying patterns during the game. The striatum was less active when the alien sounds were not consistent.

"Just like a baby, our participants weren't trying to learn anything while listening to the sounds. They just absorbed the sounds as they played the game," said Sung-Joo Lim, a Carnegie Mellon Ph.D graduate who led the study. "But it was clear they were quickly learning. They began to associate specific sounds with specific aliens in the game."

Their new research is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS). The study looks at the striatum, which has previously been tabbed as important for reward-based category learning, to see if it has a role in the brain regions that develop new sound categories.

"Our participants were focused on playing the video game, not sound category learning," said Lori Holt, a psychology professor in CMU's Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences. "Our results show that it is possible to recruit the striatum to support learning even when people are engaged in a different task as long as the sounds have a patterned structure. Without the structure, very little learning took place."

The findings were bolstered after the game, when each participant took a test about the sounds they heard in the game. Those in the experimental group performed better when asked to match sounds and alien creatures.

"Our findings indicate there is a network of brain regions that participate in extracting regularities of input from our environment that align with goal-directed behaviors to succeed in the game," said Lim, now a research assistant professor at Boston University. "The striatum is at the center of this process."

Lim and her co-authors agree that studying speech learning is hard. Sounds disappear the moment they are heard. Unlike visual clues, they can't be recovered and referenced again. It is one reason they think brain research on sound learning is understudied.

"We are born as universal listeners. We don't come into this world with a bias toward any particular language," said Julie Fiez, a psychology professor at Pitt who co-authored the study. "But somehow, our brains figure it out in that first year."

"This is a new way of studying learning that naturally takes place," Holt said. "If we can understand it better, we can hopefully find ways to make learning for adults more efficient and faster."

The study, "Role of the striatum in incidental learning of sound categories," was supported by the National Institutes of Health (T32GM081760, 5T90DA022761-07, R01DC004674, R01HD060388) and the National Science Foundation (DGE0549352, 22166-1-1121357, SBE-0839229). The content is solely the responsibility of the principal investigators and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NSF.