Packaging the Goods: Bruce McWilliams Delivers Tomorrow’s Technology and Talent

Bruce McWilliams opens a bag and pulls out a small board with two cameras, one that fits inside today’s cell phones and another that’s a few millimeters across. Each tiny camera takes the same quality pictures as a Motorola MOTORAZR™, but it costs about a dollar to make. And it’s likely to appear in your next cell phone purchase. Right now, McWilliams wants to see if he can put this miniscule camera on a robot.

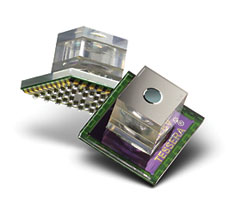

“The level of technology advancements we’ve achieved, even in the last decade, is amazing. Take one of these cameras, for instance. Using Tessera’s new 3-D chip packaging technology, we can integrate a significant amount of electronics into this tiny camera for use in a phone like the MOTORAZR or in emerging applications, like robotics,” McWilliams reflects.

Since June 1999, McWilliams has served as chief executive officer, president and a member of the board of directors of Tessera Technologies, a company whose name derives from the Greek word for tile — an apt moniker for a business that creates miniature tiles of electronics called “chip-scale” packages.

Making electronics smaller and better performing is what Tessera does well. Now in its 17th year, this company holds more than 60 licenses, creates more than $200 million in annual revenues and is worth approximately $2 billion. Tessera’s products are pervasive. Almost all cell phones contain chips using its technology. In fact, Tessera’s technology can be found in a broad range of electronics including computers, MP3 players and medical and defense electronics, from companies like Apple, Hewlett-Packard, Nokia and Sony.

Making electronics smaller and better performing is what Tessera does well. Now in its 17th year, this company holds more than 60 licenses, creates more than $200 million in annual revenues and is worth approximately $2 billion. Tessera’s products are pervasive. Almost all cell phones contain chips using its technology. In fact, Tessera’s technology can be found in a broad range of electronics including computers, MP3 players and medical and defense electronics, from companies like Apple, Hewlett-Packard, Nokia and Sony.

Supporting the Future

Such success has enabled McWilliams (S’78, ’78, ’81) to support graduate students at his alma mater — Carnegie Mellon University. In fall 2006, McWilliams and his wife Astrid endowed a graduate fellowship at the Mellon College of Science (MCS). The fellowship supports MCS graduate students conducting leading-edge research in emerging fields such as nanotechnology, biophysics and cosmology.

McWilliams appreciates the value of financial support because he came from modest financial means. As a teenager, McWilliams drafted a solution to a complex math problem and submitted it to a professor at the Carnegie Institute of Technology. He was quickly admitted with a full scholarship to Carnegie Mellon, where he finished his undergraduate and doctoral studies in physics in just seven years.

While no longer in academia, McWilliams still devotes an hour every morning to solving advanced physics problems and poring through the latest texts on quantum mechanics or general relativity.

Industrial Science

While pursuing his doctorate, McWilliams also took a job working with several Mellon Institute scientists to develop an oximeter — an external meter to measure the oxygen content of blood. While at the Mellon Institute, McWilliams also worked toencode a mathematical model on an early microprocessor.

“I did the machine code and that’s how I learned a little bit about computers,” McWilliams acknowledges modestly.

McWilliams’ next move was to the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory in 1982, where he worked alongside scientific luminaries including Edward Teller, widely known as a member of the Manhattan Project. In time, McWilliams had 130 people reporting to him and spent $30 million per year making electronics for satellites and telescopes. He also developed technology for the next generation of computers.

“We understood that packaging would be a key factor in the development of ‘next-gen’ electronics because it would help control a computer’s speed,” remembers McWilliams. “That’s how we got into chip packaging. Ultimately, this area was very important not just for scientific applications — such as satellites and telescopes — but across a wide range of industries.”

Turning Technology into Business

Marrying scientific insight with business acumen is rare. While he worked at Lawrence Livermore, McWilliams sold technology to the government and learned much about managing creative teams and salesmanship, says David Tuckerman, a long-time colleague and Tessera’s Chief Technology Officer.

Marrying scientific insight with business acumen is rare. While he worked at Lawrence Livermore, McWilliams sold technology to the government and learned much about managing creative teams and salesmanship, says David Tuckerman, a long-time colleague and Tessera’s Chief Technology Officer.

While comfortable for the present, McWilliams has had his share of business travails, launching several companies — including one that was bought out and one that folded — before finding success with Tessera.

“Life as a company CEO is like being in a foxhole with bullets flying over your head,” McWilliams acknowledges. “After you get very comfortable doing it, it’s actually a fun job provided you don’t mind having big problems every day.”

McWilliams sees his work environment as a “sandbox for scientists”— a place of constant, productive creativity, according to a July 2007 article for the Silicon Valley/San Jose Business Journal.

“It’s a culture that respects science,” adds Tuckerman, but one that’s also always focused on market opportunities.

“A CEO is supposed to deliver a successful growth of profit for his shareholders,” says McWilliams about the bottom line. “I start with a simple mathematical model and build from there. Our existing businesses tend to take a long-term view and are very predictable, which provides stable growth. However, this approach also means that, without careful planning, there could be gaps between revenue streams.”

McWilliams employs others, like Tuckerman, to find new technologies that “fill the gaps” so that Tessera continues to grow over the long term.

Supporting Risky Ideas

At Carnegie Mellon, McWilliams invests in research without that parameter in mind. Graduate students supported by his fellowship can pursue broad research agendas, many of which may not immediately yield a practical device. McWilliams has also made a strong commitment to helping steer the university by joining the Physics Department Advisory Board and recently becoming a university trustee. Whether discussing theoretical cosmology over tea or contemplating how to outfit a robot with a 2-mm camera,

McWilliams has clearly found a new sandbox at Carnegie Mellon.

“By day, I’m a business guy, but at heart, I’m a scientist. My involvement with Carnegie Mellon allows me the opportunity to live out my passion for science and research, and also help to build and support the next wave of technology advancements. I get to learn all the time about the future, which I love.”