October 2022

The Pay Attention Games

Emily Keebler, a seventh-year graduate student working with Dr. Anna Fisher, is studying how children learn to manage waiting patiently and to control impulses. Young children grow rapidly in these important self-regulation skills, facilitating their increased cooperation and collaboration in many group settings. In some situations, it is important to delay or stop an impulsive response. In other situations, one must not only stop a response but also produce a less expected one. All of this requires paying attention to situational cues. In Emily’s series of Pay Attention Games, children participate with their words and bodies in matching, movement, and naming activities. By comparing different age children’s sustained attention and inhibition, the researchers will learn how these skills develop.

While conducting research, Emily and her research associates will be wearing quality facial coverings at all times this fall. As always, children’s time in the lab each day is less than 20 minutes. Additionally, the child and researchers will be separated by distance as much as possible.

DAY ONE

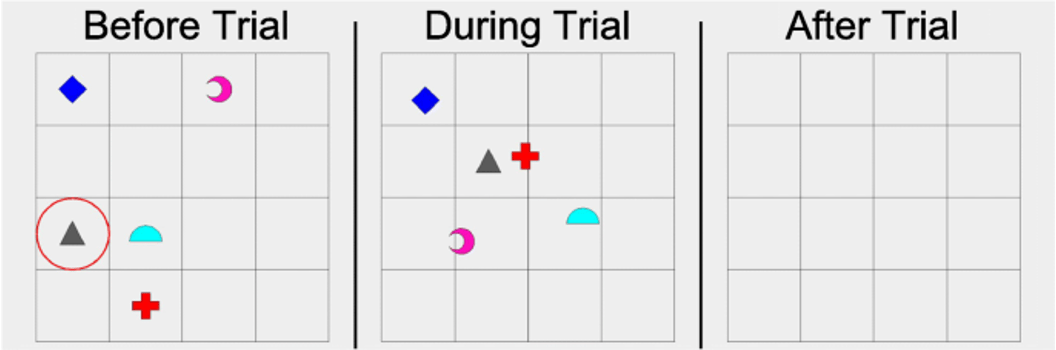

Shape Game: Children match geometric shapes using a sanitized computer keyboard. Trials vary in how much attentional control they require due to varying color/shape combinations.

Animal Matching Game: In this game, children search for animal pairs on their screen. There’s a twist in the second half of the game to keep the children on their toes.

Puppet Game: The researcher introduces two animal puppets in this game. Then both characters give children commands such as touch your nose, clap your hands.

DAY TWO

Head and Toes Game: Children get up and moving as they follow the researcher’s directions in this whole-body listening game. Children often find this one to be quite silly!

Wolf and Pig Game (Session 1): Children help to keep fictional pigs safe from wolves in this digital game! Their participation helps us to learn about how attention is deployed over time.

DAY THREE

Statue Game: In this game, children get to “freeze like a statue.” We’ll ask that they stand still and close their eyes while we play this whole-body game.

Wolf and Pig Game (Session 2): Children will play another round of the Wolf and Pig Game. Changes to the task characteristics, relative to Session 1, will help us to learn even more about children’s sustained attention.

DAY FOUR

Sorting Game: Children sort by color to create apple baskets, flower bouquets, and more in this digital task. The children stay alert to task directions, such as what to do when a worm appears!

Colorful Foods Game: Children play with unexpected images in this naming game. Care for an orange kiwi, anyone?

Picture Matching Game: In this digital activity of close looking, children identify line drawings that match target images.

The Picnic Foods Game

After children complete the series of Pay Attention Games described above, they continue to engage with Emily Keebler’s research team by playing the Picnic Foods Game, which is an opportunity for the researchers to better understand young children’s knowledge of foods and their typical colors so they can better interpret children’s performance on the Colorful Foods Game. In the Picnic Foods Game, children are first asked to state the names of foods presented as line drawings on a computer screen. In the second part of the game, the children indicate which of two colors is more typical for each food item.

The researchers expect that children have varied familiarity with the foods (for example, bananas being more familiar to most children than eggplants). Collecting this information directly from children helps the researchers to understand children’s knowledge and their reactions to the specific depictions of the foods. In addition to supporting the research efforts, The Picnic Foods Game provides children the opportunity to re-engage with the pictures from the Colorful Foods Game. In many cases, opportunities to build mastery result in new pride and confidence. Children also build flexible thinking by working with familiar images in multiple ways.

November 2022

The Matching Game

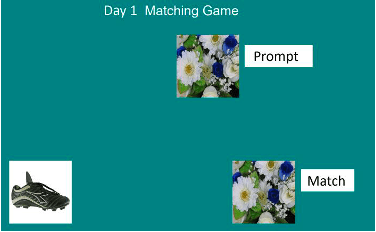

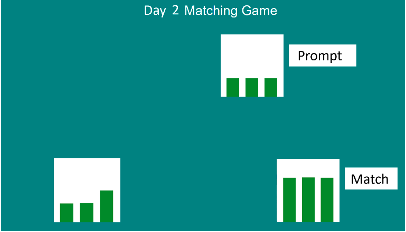

Dr. Jessica Cantlon’s research team is investigating how children learn abstract concepts and logical rules. This research has two parts conducted on two separate days. On Day 1, children play a game that involves discovering a matching rule. From two choices, they choose the one that is an identical match to the picture prompt. On Day 2, children play a similar matching game where the matches are based on patterns rather than exact identity.

Playing these games will help the researchers understand children’s learning curves for discovering simple rules so that they can then progress to studying more complex rules involving analogies or sequences. Logical reasoning is a critical skill throughout early education. Children use logical reasoning quite broadly – during reading comprehension, mathematics, science, and social interactions, etc. This study will allow researchers to better identify what aspects of logical reasoning are important to assess and cultivate in early childhood education.

Undergraduate Research Methods Course

Dr. Erik Thiessen’s Developmental Research Methods students are preparing their final projects for the semester. They are beginning to pilot test their projects on the topics listed below. Families whose children participate will receive fuller parent descriptions via the child’s backpack. Everyone can read the study descriptions on the Research Bulletin Board near the office door. Notice the interesting and important topics in early childhood development!

- Does awareness of time constraints hinder performance on a memory task?

(The Memory Matching Game, Preschool 4’s and Kindergartners) - Does a commercial highlighting the accomplishments of a black female facilitate memory for facts about black characters in a simple story, compared to a commercial about a white female or no commercial? (The Get to Know You Game, Preschool 3’s and Preschool 4’s)

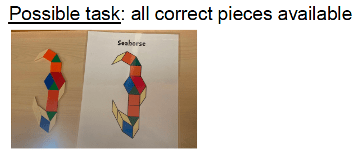

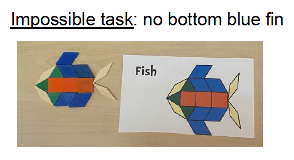

- Does affirming a growth mindset in children increase their persistence to continue with challenging tasks (both possible and impossible), compared to simple affirmations of positive attributes? (The Shape Game, Preschool 4’s and Kindergartners)

.

.

The Number Game

Drs. Jessica Cantlon and Lauren Aulet are investigating how children learn number symbols, such as Arabic numerals, and whether this process may be influenced by using spatial tools such as a number line. Over several sessions, children complete two tasks: a Number Line task and a Number Comparison task. In both tasks, children are shown Arabic numerals on a touchscreen computer and then answer questions about the numerals they are shown.

Because young children’s ability to understand basic numbers such as 1 – 9 and their ability to represent these numbers spatially has been shown to predict later math ability, we hope that by better understanding these processes, we will be able to develop educational interventions designed to improve children’s mathematical abilities.

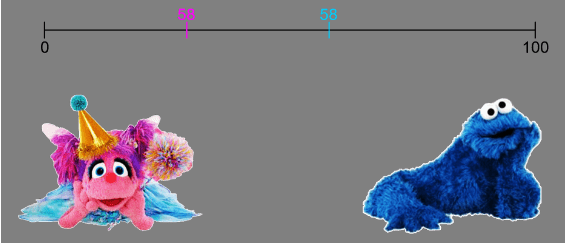

Number Line Task: Children are shown two marks on a number line and asked which one corresponds to the correct location of the numeral shown (see example image below). Specifically, researchers tell children that Abby and Cookie Monster have answered where they think the number goes on the number line. The child then indicates whether Abby or Cookie Monster answered correctly by tapping the character’s image.

Number Line Task: Children are shown two marks on a number line and asked which one corresponds to the correct location of the numeral shown (see example image below). Specifically, researchers tell children that Abby and Cookie Monster have answered where they think the number goes on the number line. The child then indicates whether Abby or Cookie Monster answered correctly by tapping the character’s image.

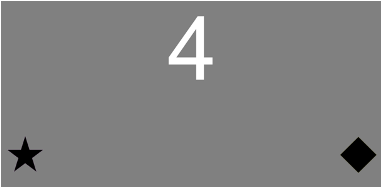

Number Comparison Task: Children are shown an Arabic numeral ranging from 1 – 9 and will be asked to answer whether the number is less or more than 5 by clicking the appropriate button on screen (bottom left button for ‘less than 5’ and bottom right button for ‘more than 5’).

Number Comparison Task: Children are shown an Arabic numeral ranging from 1 – 9 and will be asked to answer whether the number is less or more than 5 by clicking the appropriate button on screen (bottom left button for ‘less than 5’ and bottom right button for ‘more than 5’).

The Storytelling Game

Researchers in Dr. Erik Thiessen’s lab aim to understand how the presentation of a story can affect a child’s reading comprehension and storytelling abilities. Children hear short, fiction stories by Thacher Hurd read by a narrator on a tablet. After each line is read, the child repeats the words. To test how the mode of a story affects children, the stories either have contingent animation, where the animation moves in response to the child’s repetitions, or static animation, where the images do not move. At the end of the story, the narrator asks the child a series of a dozen prerecorded questions and the child answers out loud. The narrator automatically moves from one question to the next in a set amount of time without providing any feedback to the child on the accuracy of their responses, and the tablet records the audio of the responses. The researchers plan to compare children’s responses when engaging with the contingent animation story vs. the no animation story to see how the modes of stories can affect children’s reading comprehension and storytelling. These findings will help us understand how children learn and how modes of animation can potentially enhance their learning processes.

The Picture Game

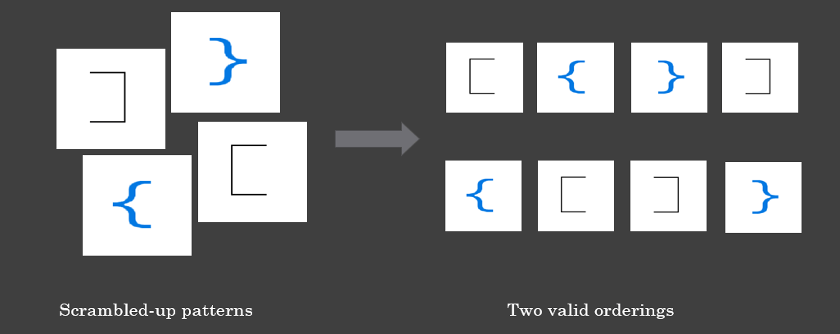

Dr. Jessica Cantlon and graduate student Abhishek Dedhe are investigating how children use simple logical rules to process complex visual patterns. This game happens over several sessions. Researchers teach the child to complete two tasks involving visual patterns: shapes and brackets. Both tasks rely on logical rules about repetition, hierarchies, and symmetry. By having the child perform these challenging tasks, researchers can examine how the child’s understanding of these logical rules improves. A visualization of the bracket task is included at the bottom of this page. The shape task looks very similar, except that it has unknown shapes that look like keyboard characters (@, !, #) instead of brackets.

In the Picture Game, the child completes two tasks. Since each child progresses at their own speed, they might need more than one session to complete them. First, researchers teach the child the correct order of a sequence of four shapes or brackets. These four shapes or brackets are shown scrambled on the screen, and the child touches them in the correct order. Our robot friend Rajah helps the child know if they're on the right track. Once researchers establish that the child has understood the task, they are shown sets of scrambled shapes or brackets and asked to select them in the correct order. However, this time Rajah does not tell them whether they are right or wrong.

Bracket task:

For example, in one bracket task, the child is told that these four brackets occur in the shown order (first - second - third - fourth). They are then shown the following four scrambled brackets and asked to touch them in the correct order. In this case, there are two equally correct orders.

The Additional Picture Games

Researchers play additional games with the children to determine whether their Picture Game performance is related to any other cognitive process, such as working memory, motor skills, and language comprehension. They assess working memory because the more a child can remember the visual patterns in their heads, the easier the game should be. They are also checking whether the child can utilize these simple logical rules based on repetition, hierarchies, and symmetry in domains unrelated to vision. These domains include language and movement. All these tasks provide researchers with context when they examine results from the Picture Game. This context allows them to be more confident about the meaning of their research findings. It might even reveal some connections they might not have expected!

- In the Zoo Locations Game, researchers have zoos with different amounts of exhibits, each with different animals. After viewing the zoo’s arrangement, children are given an empty zoo and asked to place each animal where they belong. This task checks children’s working memory.

- In the Picture Memory Game, children see a picture of several common objects (like an apple or a kite) and then another picture with those same objects mixed with others. Researchers then ask them to point to the objects they saw on the prior page. This task also examines working memory, but in a slightly different way. Using both games together provides a clearer measure of children’s working memory ability.

- In the Number Game, researchers ask the child to listen to a list of numbers and then repeat them both in forward and backward order. This task also taps working memory, but unlike the zoo location and picture memory games which measure visual working memory, this game measures verbal working memory.

- In the Language Comprehension Game, researchers show the child a picture of several colored shapes and ask them to point to specific objects they see (such as “the second small green circle”). This task allows us to examine general language comprehension (does the child know the meaning of “green” or “circle”?), as well as examining how the child combines different words to grasp the overall meaning (such as the difference between a “small circle”, a “green circle”, and a “small green circle”).

In the Tower of Hanoi Game, the child uses a classic toy consisting of movable disks that can be slid onto wooden poles. Researchers ask the child to move the disks from one pole to another according to certain rules (such as “you cannot put a bigger disk on a smaller disk”). This task examines whether your child can plan their future moves so that they satisfy specific conditions.

In the Tower of Hanoi Game, the child uses a classic toy consisting of movable disks that can be slid onto wooden poles. Researchers ask the child to move the disks from one pole to another according to certain rules (such as “you cannot put a bigger disk on a smaller disk”). This task examines whether your child can plan their future moves so that they satisfy specific conditions.- In the Corsi Block-Tapping Game, children are shown a screen display of up to nine identical spatially separated blocks. A researcher will tap on the blocks in a particular sequence and the child’s task is to tap them in the same order. The sequence starts simple, usually with only two blocks, but it becomes progressively more complex. This task assesses the child’s visuo-spatial short-term working memory.

December 2022

The Story Time Games

In collaboration with Dr. Anna Fisher, Post-Doctoral Fellow Catarina Vales is leading a research team in examining whether children’s understanding of racial categories is malleable via influences from children’s literature. Prior research shows that popular books for young children are more likely to include white characters and anthropomorphized nonhuman characters engaging in mundane human behaviors (e.g., a dinosaur’s bedtime routine) than they are to include people of color as main characters. In this project, researchers want to tackle this disheartening reality by counteracting the lopsided statistics present in most children's picture book collections.

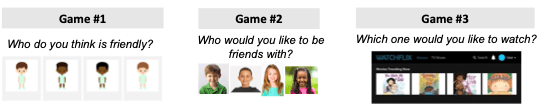

To do so, they purposefully selected commercially available picture books for children in which the main characters are people of color engaging in simple, everyday activities. They will read one book to small groups of children daily (Monday through Thursday), over the course of 4 weeks. To assess the effect of reading these books on children’s understanding of racial categories, the researchers invite children to complete three thinking games before and after the 4 weeks of shared book reading. In the first game, children are asked which people (some dark- and some light-skinned) are more likely to have a certain trait (e.g., being a good friend; not cleaning up after themselves). In the second game, children are shown dark- and light-skinned people and asked with whom they would like to be friends. In the third game, children are shown a media catalog depicting media with dark- and light-skinned characters and are asked which they would like to watch. The results of this longitudinal study will help the researchers understand whether children’s experiences with inclusive picture books can be harnessed to decrease racial biases in children.

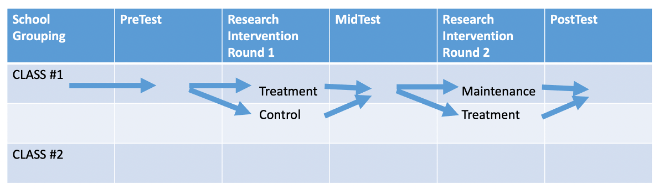

There is an interesting design being used in this study:The Now & Later Design. All the children in the Preschool 3’s, Preschool 4’s, and Kindergarten classes will participate in the Pre-Test phase of the research during December, but then only half of each class (the treatment group) will participate in the story reading sessions starting in January. Then, everyone will be tested again to see if there is more of a change in the treatment group than the “controls”. At that point, the other half of each class will participate in the story reading sessions before everyone gets tested one final time on games 1-3. The Post-Tests will show both whether similar treatment effects are seen with a second set of children AND whether any treatment effects seen in the first set are maintained without additional story reading. We will keep you posted!

January 2023

The Matching Game

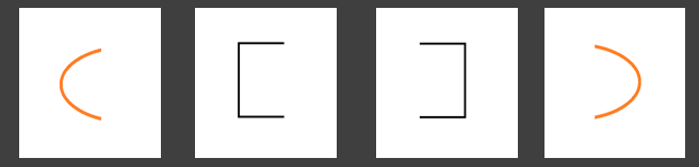

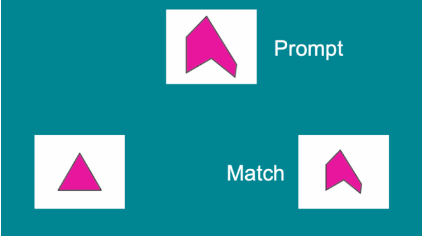

Dr. Jessica Cantlon’s research team is investigating how children learn abstract concepts and logical rules. This research has two parts to it, and it will be conducted on three separate days over a period of a week or two. On Days 1 and 2, children play a simple game in which they are encouraged to discover a matching rule; they choose a shape from two options that is identical to a sample shape. An example of this is shown below. Similarly, on Day 3 children play a matching game of the same format to see if they successfully learned the rule.

These games will help researchers understand children’s learning curves for discovering simple rules, so they can build on the findings to study more complex rules, such as rules that require learners to see patterns, analogies, or sequences. In this study, researchers are studying how long it takes children to discover and learn a simple rule like ‘match the pictures’ and then how well they stick to the rule once they learn it. In a subsequent study, they will investigate a more complex rule like pattern matching using the same kind of game. Researchers can then compare learning curves from the simple rule to the more complex rule to determine how children at different ages build capacities to discover new rules and maintain the rules they learn across different levels of rule complexity. Logical reasoning is a critical skill throughout early education. Children use logical reasoning quite broadly, e.g., during reading comprehension, mathematics, science, computer coding, and social interactions. This study will allow researchers to better identify what aspects of logical reasoning are important to assess and cultivate for early childhood education.

These games will help researchers understand children’s learning curves for discovering simple rules, so they can build on the findings to study more complex rules, such as rules that require learners to see patterns, analogies, or sequences. In this study, researchers are studying how long it takes children to discover and learn a simple rule like ‘match the pictures’ and then how well they stick to the rule once they learn it. In a subsequent study, they will investigate a more complex rule like pattern matching using the same kind of game. Researchers can then compare learning curves from the simple rule to the more complex rule to determine how children at different ages build capacities to discover new rules and maintain the rules they learn across different levels of rule complexity. Logical reasoning is a critical skill throughout early education. Children use logical reasoning quite broadly, e.g., during reading comprehension, mathematics, science, computer coding, and social interactions. This study will allow researchers to better identify what aspects of logical reasoning are important to assess and cultivate for early childhood education.

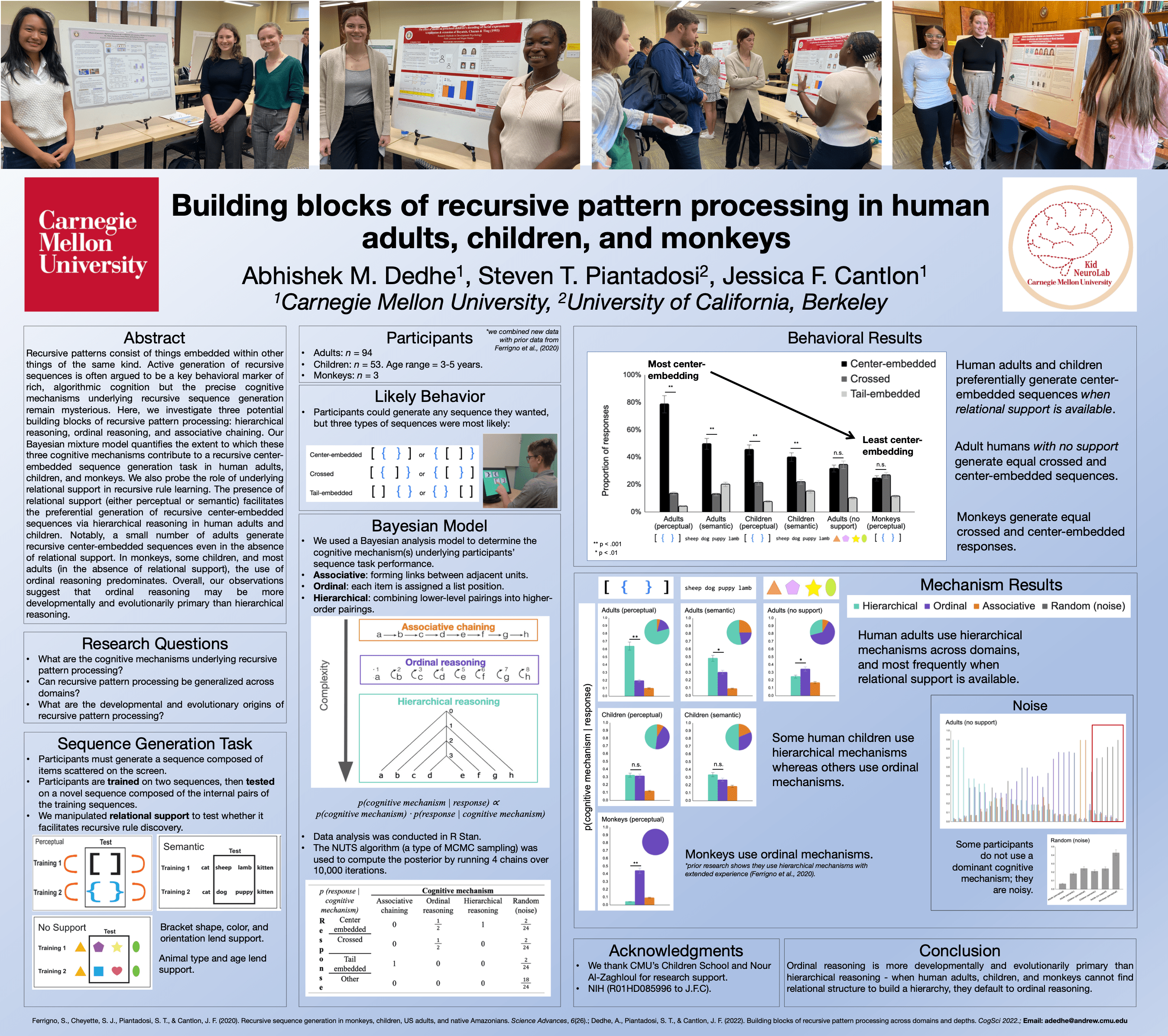

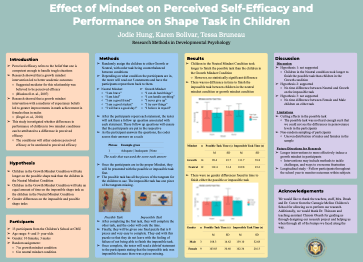

Research Methods Posters

The three developmental research groups from Fall 2022 presented their projects and discussed their findings at a poster session in early December, along with students from the cognitive and social methods classes. The group whose poster is shown to the right won the award for the best study. Note that the criteria relate to the study design and description, not necessarily finding results that align with the study hypotheses. It’s learning the process that counts!

February 2023

The Moving Shapes Game

The world around us is complex, so maintaining focused attention can sometimes be challenging, even for adults. Professor Anna Fisher and Research Associate Amanda Lee are investigating the developmental course of focused attention and examining factors that play a role in this ability at different points in development. They will use an exciting game played on a computer with an eye tracking instrument that is attached to the computer monitor (see the green arrow).

The world around us is complex, so maintaining focused attention can sometimes be challenging, even for adults. Professor Anna Fisher and Research Associate Amanda Lee are investigating the developmental course of focused attention and examining factors that play a role in this ability at different points in development. They will use an exciting game played on a computer with an eye tracking instrument that is attached to the computer monitor (see the green arrow).

In the Moving Shapes Game, children see several geometric shapes moving on a grid on the computer screen. Children are asked to watch a particular object while ignoring the rest of the objects. When the objects stop moving and disappear from the screen, children are asked to point to the grid cell inside which the target object disappeared.

In this study, researchers are interested in measuring a specific aspect of attentional development between ages 3 and 6, which is a period of rapid development in children’s ability to engage their attention selectively toward chosen goals and tasks. Researchers will measure whether the fraction of time that children spend in an ostensibly “optimally engaged” mode of attending increases with age, while at the same time the fraction of time they spend in a relatively more “distractible” mode of attending decreases with age. In particular, they will measure how children’s eye movement behavior, reflecting relative task engagement, is related to their pupil diameter activity, a well-researched proxy measure of activity in a specific brain pathway supporting alertness and attention.

The results of this study can help researchers biologically ground a model of attention and attention development that they previously developed and tested, which will give them greater confidence in applying and further developing the model to predict and understand typical development of attentional function, as well as individual variations in attentional style. This information could potentially inform parents and educators in efforts to structure children’s learning experiences more effectively.

March 2023

The Picture Taking Game

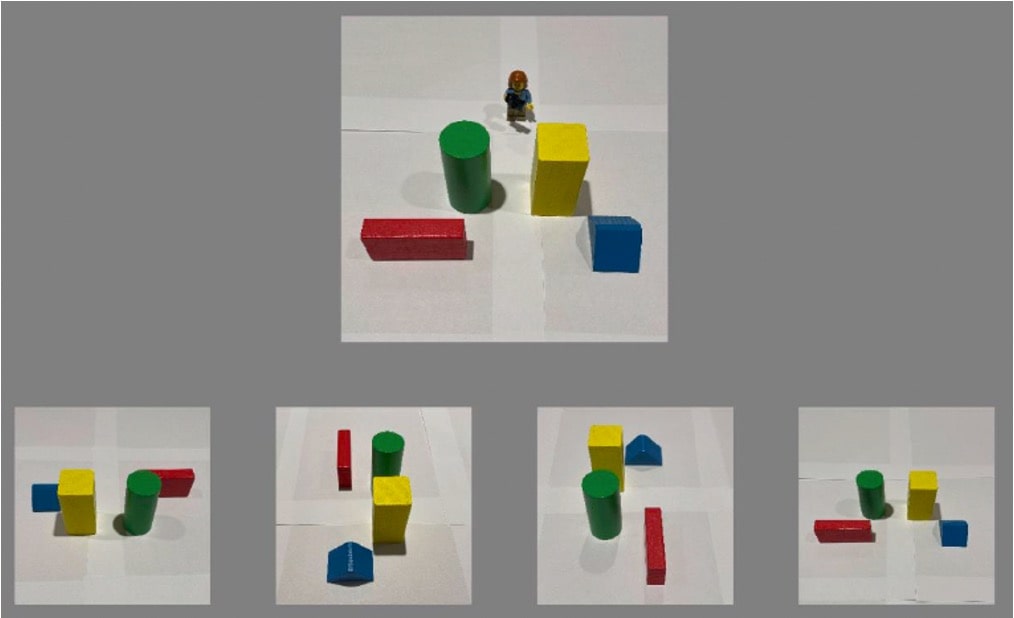

Karen Sabol is a senior cognitive science major working on her thesis with Drs. Jessica Cantlon and Lauren Aulet. In the Picture Taking Game, Karen is investigating how children develop spatial perspective-taking skills. Spatial perspective-taking is a three-dimensional spatial skill that allows you to imagine what something would look like from a different viewpoint.This task consists of a short spatial perspective-taking task presented on a touchscreen computer. In the task, the children see an image of a LEGO figurine holding a camera and “taking a Picture” of another toy or set of toys. The children are then asked to select which picture the LEGO figurine took (see example below).

Previous research has indicated that spatial perspective-taking is a consistent predictor of math abilities, at least in children between first and eighth grade. The results of this study will help Karen learn how spatial perspective-taking skills vary in younger age groups (Preschool 4’s vs. Kindergarten), as well as by gender. Future analyses using these data will also shed light on how the development of spatial perspective-taking skills relates to the development of other spatial and math skills being studied in the same lab (see November 2022 and January 2023 newsletters). Ultimately, these results may contribute to educational interventions to help children improve their math abilities.

April 2023

Research Methods Final Projects

The students in Dr. Caterina Vales’ Research Methods class have proposed, piloted, and almost finished conducting their small group final projects for the semester.

The Memory Game

These student researchers investigate how children’s use of interactive story technology affects story content recall compared with traditional book reading. As a comparison, the researchers had the children recall as many object pictures presented one at a time as they could, with some children seeing the pictures displayed on a digital tablet and others seeing paper flashcards. Based on prior research, the team predicted that children would perform better in the story recall task compared to the picture recall task, regardless of the presentation medium. They also hypothesized children would perform better with digital materials than traditional paper because of the extra engagement with technology.

The Story Game

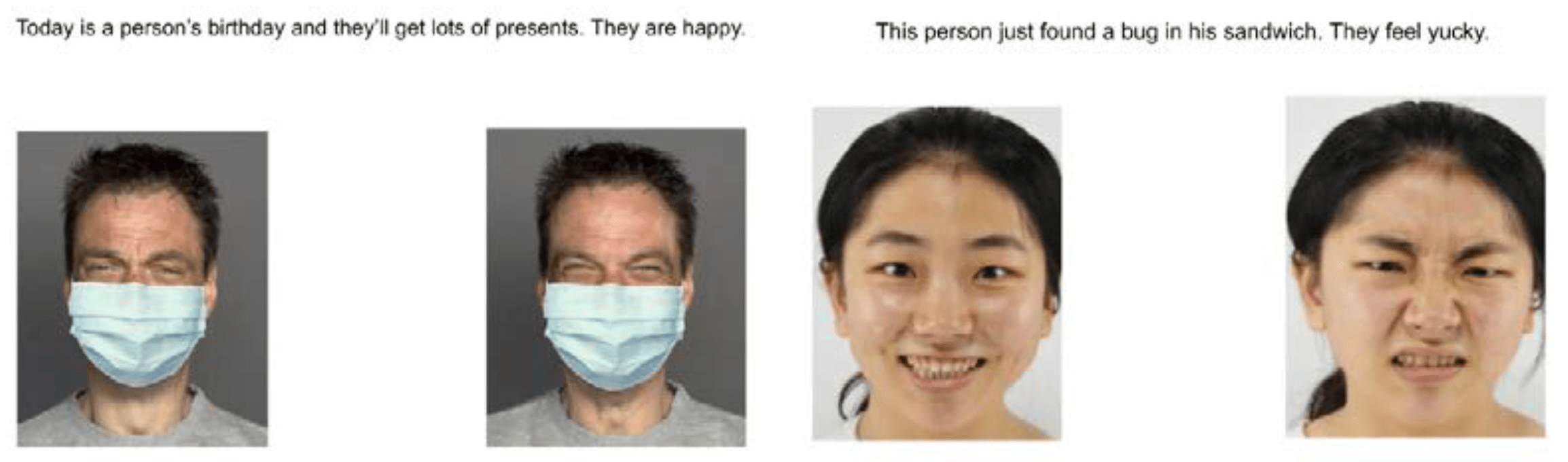

This team examined children’s ability to decode facial expressions with and without masks. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increase in the use of facial masks in many social settings, raising the possibility that this could impact children's ability to identify emotions. On each trial, the child hears a very brief scenario and sees two photographs of the same person showing two different emotions. On some trials, the person is wearing a facial covering and on some there are no masks. If results show that children decode facial expressions better without masks, it is most likely because masks cover half the face and occlude important facial features like the nose and mouth. On the other hand, if children decode emotion better in the masked condition, it might be because they have been exposed to masks during their early childhood. Therefore, they may be able to decode emotional information with only partial information available.

The Matching Feelings to Faces Game

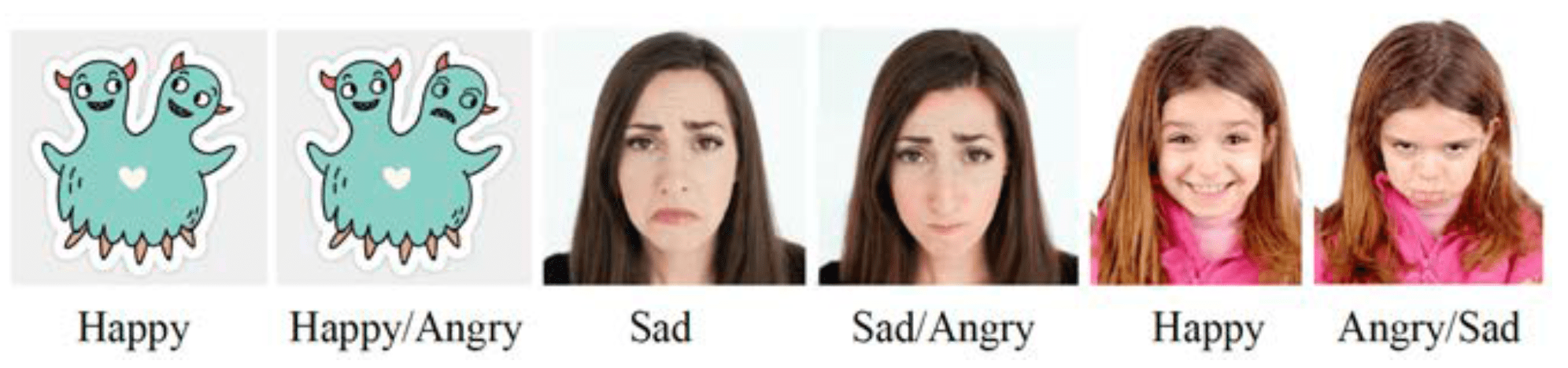

This student team examined children’s ability to identify mixed emotions vs. singular emotions. On each trial, the researcher shows one photo of a facial expression (either a child, an adult, or a two-headed imaginary creature). Facial expressions included happy, sad, mad, or a combination of two of them. Based on prior research, the team hypothesized that children would be less likely to identify mixed emotions on a child or adult’s facial expression than they would on a two-headed imaginary creature where the two emotions are represented separately. The importance of this research game is to understand children’s ability to recognize simple versus complex emotions.

May 2023

In many cases, research conducted at the Children’s School is early career training for undergraduate researchers, graduate students, and post-doctoral fellows working in faculty labs, and it often includes pilot work in the early stages of the research cycle. Part of these essential processes involves learning to summarize key elements of projects to present them succinctly in professional settings in order to receive substantive feedback that will then guide future research. The Research Methods students recently held their spring poster session, and below is a graduate student poster about research that will be presented this month at the Vision Sciences Society conference. Similar research will continue during the June camp next month (see January’s Matching Game description).