October 2021

The Board Game

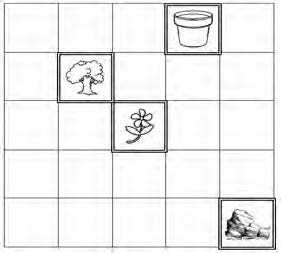

Dr. Catarina Vales, a post-doctoral researcher working with Dr. Anna Fisher, is working with her research team to examine how specific aspects of language help children learn relations among concepts -- such as “cat” and “dog” both being animals, and “cat” and “leash” sharing a functional relation. Using a text corpus of English child-directed speech, the team selected items that are likely to be mentioned in language (1) close in time (for example, in the same sentence), (2) in similar contexts (for example, in similar sentences), or (3) both close in time and in similar contexts. In session 1 of this study, children are asked to organize cards depicting those items by placing close together items that they think go together. Researchers use the spatial distance between the cards to infer which types of items children think are more strongly related. In session 2 of this study, children are asked to organize those same items on a computer. The results of this study will help researchers better understand what properties of language contribute to learning relations among concepts, and whether a computerized version of the board game can be used in future studies.

Dr. Catarina Vales, a post-doctoral researcher working with Dr. Anna Fisher, is working with her research team to examine how specific aspects of language help children learn relations among concepts -- such as “cat” and “dog” both being animals, and “cat” and “leash” sharing a functional relation. Using a text corpus of English child-directed speech, the team selected items that are likely to be mentioned in language (1) close in time (for example, in the same sentence), (2) in similar contexts (for example, in similar sentences), or (3) both close in time and in similar contexts. In session 1 of this study, children are asked to organize cards depicting those items by placing close together items that they think go together. Researchers use the spatial distance between the cards to infer which types of items children think are more strongly related. In session 2 of this study, children are asked to organize those same items on a computer. The results of this study will help researchers better understand what properties of language contribute to learning relations among concepts, and whether a computerized version of the board game can be used in future studies.

The Pay Attention Games

Emily Keebler, a sixth-year graduate student working with Dr. Anna Fisher, is studying how children learn to manage waiting patiently and to control impulses. Young children grow rapidly in these important selfregulation skills, facilitating their increased cooperation and collaboration in many group settings. In some situations, it is important to delay or stop an impulsive response. In other situations, one must not only stop a response but also produce a less expected one. All of this requires paying attention to situational cues. In Emily’s series of Pay Attention Games, children participate with their words and bodies in matching, movement, and naming activities. By comparing different age children’s sustained attention and inhibition, the researchers will learn how these skills develop. While conducting research, Emily and her research associates will be following all of the Children’s School risk mitigation strategies. As always, children’s time in the lab each day is less than 20 minutes, and the child and researcher will be separated by distance as much as possible.

DAY ONE

- Shape Game: Children match geometric shapes using a sanitized computer keyboard. Trials vary in how much attentional control they require due to varying color/shape combinations.

- Animal Matching Game: In this game, children search for animal pairs on their screen. There’s a twist in the second half of the game to keep the children on their toes.

- Puppet Game: The researcher introduces two animal puppets in this game. Then both characters give children commands such as touch your nose, clap your hands.

DAY TWO

- Head and Toes Game: Children get up and moving as they follow the researcher’s directions in this whole-body listening game. Children often find this one to be quite silly!

- Wolf and Pig Game (Session 1): Children help to keep fictional pigs safe from wolves in this digital game! Their participation helps us to learn about how attention is deployed over time.

DAY THREE

- Statue Game: In this game, children get to “freeze like a statue.” We’ll ask that they stand still and close their eyes while we play this whole-body game.

- Wolf and Pig Game (Session 2): Children will play another round of the Wolf and Pig Game. Changes to the task characteristics, relative to Session 1, will help us to learn even more about children’s sustained attention.

DAY FOUR

- Sorting Game: Children sort by color to create apple baskets, flower bouquets, and more in this digital task. The children stay alert to task directions, such as what to do when a worm appears!

- Colorful Foods Game: Children play with unexpected images in this naming game. Care for an orange kiwi, anyone?

- Picture Matching Game: In this digital activity of close looking, children identify line drawings that match target images.

November 2021

The Picture Game

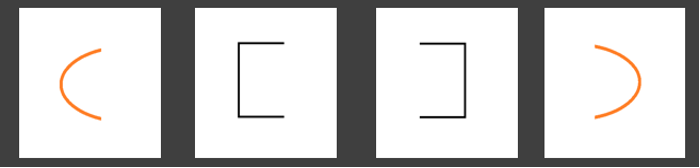

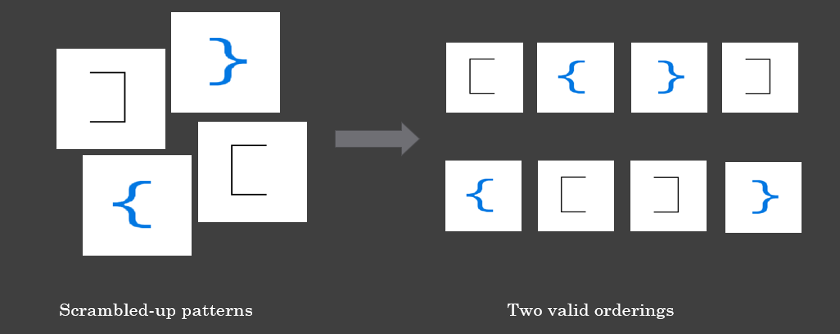

Dr. Jessica Cantlon, Nour al-Zaghloul, and Abhishek Dedhe are investigating how children use simple logical rules to process complex visual patterns. This game happens over several sessions. Researchers teach the child to complete two tasks involving visual patterns: shapes and brackets. Both tasks rely on logical rules about repetition, hierarchies, and symmetry. By having the child perform these challenging tasks, researchers can examine how the child’s understanding of these logical rules improves. A visualization of the bracket task is included at the bottom of this page. The shape task looks very similar, except that it has unknown shapes that look like keyboard characters (@, !, #) instead of brackets.

In the Picture Game, the child completes two tasks. Since each child progresses at their own speed, they might need more than one session to complete them. First, researchers teach the child the correct order of a sequence of four shapes or brackets. These four shapes or brackets are shown scrambled on the screen, and the child touches them in the correct order. Our robot friend Rajah helps the child know if they're on the right track. Once researchers establish that the child has understood the task, they are shown sets of scrambled shapes or brackets and asked to select them in the correct order. However, this time Rajah does not tell them whether they are right or wrong.

Bracket task:

For example, in one bracket task, the child is told that these four brackets occur in the shown order (first - second - third - fourth). They are then shown the following four scrambled brackets and asked to touch them in the correct order. In this case, there are two equally correct orders.

The Additional Picture Games

Researchers play additional games with the children to determine whether their Picture Game performance is related to any other cognitive processed, such as working memory, motor skills, and language comprehension. They assess working memory because the more a child can remember the visual patterns in their heads, the easier the game should be. They are also checking whether the child can utilize these simple logical rules based on repetition, hierarchies, and symmetry in domains unrelated to vision. These domains include language and movement. All these tasks provide researcher with context when they examine results from the Picture Game. This context allows them to be more confident about the meaning of their research findings. It might even reveal some connections they might not have expected!

- In the Zoo Locations Game, researchers have zoos with different amounts of exhibits, each with different animals. After viewing the zoo’s arrangement, children are given an empty zoo and asked to place each animal where they belong. This task checks children’s working memory.

- In the Picture Memory Game, children see a picture of several common objects (like an apple or a kite) and then another picture with those same objects mixed with others. Researchers then ask them to point to the objects they saw on the prior page. This task also examines working memory, but in a slightly different way. Using both games together provides a clearer measure of children’s working memory ability.

- In the Number Game, researchers ask the child to listen to a list of numbers and then repeat them both in forward and backward order. This task also taps working memory, but unlike the zoo location and picture memory games which measure visual working memory, this game measures verbal working memory.

- In the Language Comprehension Game, researchers show the child a picture of several coloured shapes and ask them to point to specific objects they see (such as “the second small green circle”). This task allows us to examine general language comprehension (does the child know the meaning of “green” or “circle”?), as well as examining how the child combines different words to grasp the overall meaning (such as the difference between a “small circle”, a “green circle”, and a “small green circle”).

- In the Tower of Hanoi Game, the child uses a classic toy consisting of movable disks that can be slid onto wooden poles. Researchers ask the child to move the disks from one pole to another according to certain rules (such as “you cannot put a bigger disk on a smaller disk”). This task examines whether your child can plan their future moves so that they satisfy specific conditions.

- In the Corsi Block-Tapping Game, children are shown a screen display of up to nine identical spatially separated blocks. A researcher will tap on the blocks in a particular sequence and the child’s task is to tap them in the same order. The sequence starts simple, usually with only two blocks, but it becomes progressively more complex. This task assesses the child’s visuo-spatial short-term working memory.

December 2021

The Creative Spelling Game

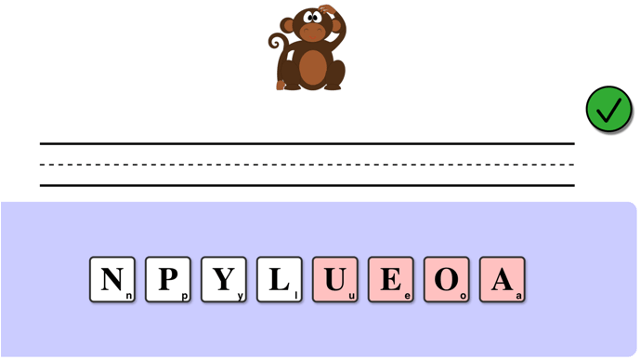

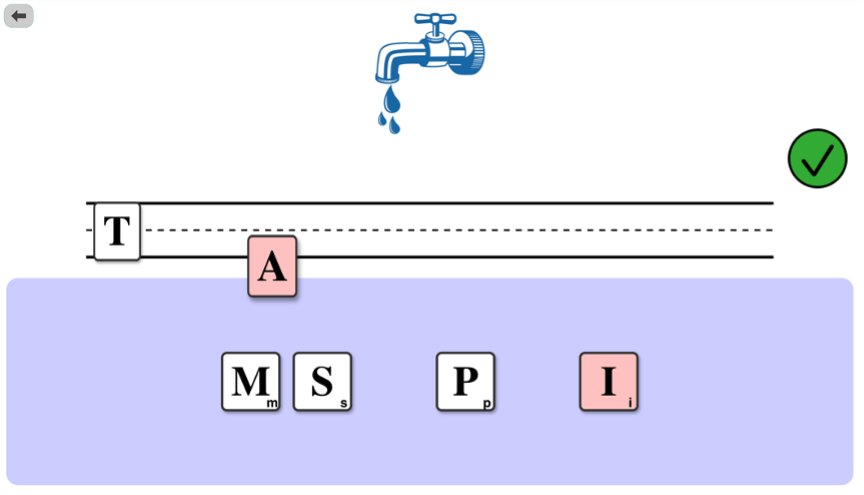

Graduate students Patience Stevens (Psychology) and Danny Weitekamp (Human Computer Interaction) from the Program in Interdisciplinary Education Research are collaborating to design and test an app that gives children practice generating the spellings of words. As children learn to read and spell, they are often encouraged to try spelling words based on how they sound. This practice can lead to “invented spellings” like CHEZ for “cheese” and MAPO for “maple”. Trying invented spellings proves to be very helpful for improving children’s ability to spell and learn new words, but only if they are given feedback on their spellings. Patience and Danny are developing an app to give automatic feedback on children’s invented spellings. In the spring, once the app has been fully developed, they will be investigating whether using it improves children’s literacy skills as they predict. Currently, they are interested in determining whether the app is easy and fun for kindergarten-aged children. They are also pilot testing the tasks they designed to measure literacy skills, to make sure they are quick to administer and informative as evidence of children’s literacy skills.

The Video Call Games

Emily Keebler, a sixth-year graduate student working with Dr. Anna Fisher, is studying how children learn to manage waiting patiently and controlling impulses. Earlier this year, children participated in her series of Pay Attention Games (October 2021 Newsletter), that were designed to test sustained attention, inhibition, and how these are developing in young children. The Video Call Games are an opportunity for Emily’s team of researchers to hone skills in conducting research over Zoom video conferencing technology. A researcher onsite at the Children’s School provides supervision and support to the child while a separate researcher (in a different location) engages the child in the Pay Attention Games via Zoom. Once the researchers refine skills in computer-mediated research, they will be able to invite families across the country to participate in the Pay Attention Games from their homes. Our children are an important part of the research preparations to engage more families and to extend our research findings to a much broader sample! For the children, doing some of these research tasks again offers the opportunity to build mastery, which results in pride and confidence. They also build flexible thinking by participating in familiar research games in a new medium.

January 2022

The Alien Learning English Game

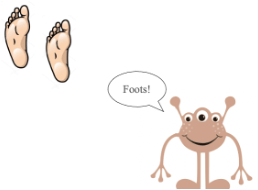

Graduate student Megan Waller is working with Psychology Professors Bonnie Nozari and Dan Yurovsky to explore young children’s metalinguistic knowledge. Over the first few years of life, children develop an incredible facility with their native language. However, there is often a disconnect between children's (and adults') correct use of language and their explicit knowledge of its rules. Such “metalinguistic” knowledge can be helpful in learning new words and in identifying when others may not be native speakers. The Alien Learning English Game is designed to determine when and how children develop the kind of metalinguistic knowledge adults have. In particular, the researchers are studying when children understand that irregular English words like "mouse" should be made plural as "mice" but not as "mouses." Children tend to produce the right versions of these words in their own speech by the time they are 4 or 5, but psychologists do not yet know whether they explicitly know that "mouses" is wrong. In the game, children are introduced to an alien named Mido who is trying to learn English. In each round of the game, Mido is shown a picture (e.g., of two mice) and asked what he thought the right word in English was. On some rounds, Mido correctly responds "mice;" while on other rounds, he responds "mouses" or "cats." Children are then asked to indicate whether Mido is speaking English correctly or not. The results of this experiment will help the researchers to understand how children develop metalinguistic knowledge of their native language. In future studies, they will investigate the relationship between this developing metalinguistic knowledge and the strategies that children use to learn new words.

Graduate student Megan Waller is working with Psychology Professors Bonnie Nozari and Dan Yurovsky to explore young children’s metalinguistic knowledge. Over the first few years of life, children develop an incredible facility with their native language. However, there is often a disconnect between children's (and adults') correct use of language and their explicit knowledge of its rules. Such “metalinguistic” knowledge can be helpful in learning new words and in identifying when others may not be native speakers. The Alien Learning English Game is designed to determine when and how children develop the kind of metalinguistic knowledge adults have. In particular, the researchers are studying when children understand that irregular English words like "mouse" should be made plural as "mice" but not as "mouses." Children tend to produce the right versions of these words in their own speech by the time they are 4 or 5, but psychologists do not yet know whether they explicitly know that "mouses" is wrong. In the game, children are introduced to an alien named Mido who is trying to learn English. In each round of the game, Mido is shown a picture (e.g., of two mice) and asked what he thought the right word in English was. On some rounds, Mido correctly responds "mice;" while on other rounds, he responds "mouses" or "cats." Children are then asked to indicate whether Mido is speaking English correctly or not. The results of this experiment will help the researchers to understand how children develop metalinguistic knowledge of their native language. In future studies, they will investigate the relationship between this developing metalinguistic knowledge and the strategies that children use to learn new words.

The Matching Game

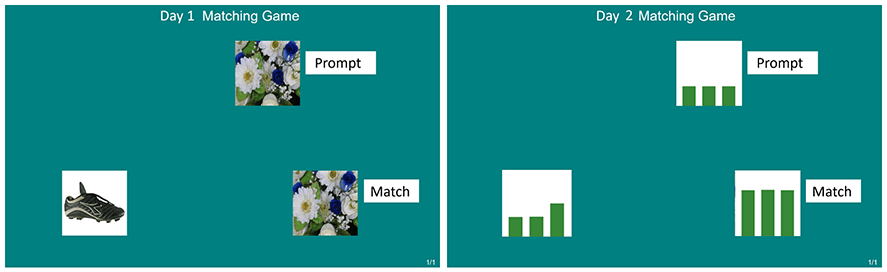

Dr. Jessica Cantlon’s research team is investigating how children learn abstract concepts and logical rules. The Matching Game has two parts and will be conducted on two separate days to help researchers understand children’s learning curves for discovering simple rules, like ‘match the pictures’, and how well they stick to the rule once they learn it. On the second day, researchers will study a more complex rule, like pattern matching. Researchers can then compare learning curves from the simple rule to the more complex rule to determine how children at different ages build capacities to discover new rules and maintain the rules they learn across different levels of rule complexity. Logical reasoning is a critical skill throughout early education. Children use logical reasoning quite broadly – during reading comprehension, mathematics, science, computer coding, social interactions. This study will help identify what aspects of logical reasoning are important to assess and cultivate for early childhood education.

February 2022

Observations for Psychology Assignments

Given the continued challenges of the pandemic, students from the Principles of Child Development class, taught this spring by Dr. Lauren Burakowski, will continue to conduct their observations using our remote observation system. For each assignment, they will observe specific differences between preschoolers and kindergartners in motor skills, social interactions, language, etc. This photo shows the way that our Kindergarten room looks during an activity time observation of fine and gross motor skill.

Given the continued challenges of the pandemic, students from the Principles of Child Development class, taught this spring by Dr. Lauren Burakowski, will continue to conduct their observations using our remote observation system. For each assignment, they will observe specific differences between preschoolers and kindergartners in motor skills, social interactions, language, etc. This photo shows the way that our Kindergarten room looks during an activity time observation of fine and gross motor skill.

Research Methods Class Studies

Dr. Burakowski is also teaching the annual Developmental Research Methods class, which will return to in person research this semester. All of the students have up-to-date COVID vaccinations, including the booster, and they are required to do weekly Tartan Testing unless they have had COVID-19 within the past 90 days. They will follow all of our protocols for facial coverings, handwashing, staying home if they experience symptoms, etc., and they spend very short times with any one child (maximum of 20 minutes but typically much less).

In mid-February, the student researchers will be collecting data for a class project on response inhibition (The Matching Pictures Game). Response inhibition refers to our ability to refrain from making a response that was correct previously but is no longer adaptive or accurate. Typically, a 2-year-old who learns how to play a game by one rule is not able to adapt their response once the rules have changed, while a 5-year-old can often inhibit the prepotent response to the first rule and play by the new rule. Students in the Research Methods class will investigate age-related changes in children’s response inhibition. Specifically, children see a target picture on a touchscreen and then scan several pictures shown below the target and tap the matching picture. To build a prepotent response, the match appears on the same side of the screen for a few trials, but then it switches to the opposite side. The researchers will measure the child’s reaction time and accuracy to see if inhibiting the tendency to tap pictures on the initial side of the screen causes errors or slower reaction times when the side switches. Based on existing evidence, they expect 3-year-olds to make more errors and show a bigger delay in responding and compared to 5-year-olds. This game taps underlying mechanisms that are similar to the “Simon Says” game, which you can play at home!

As a bonus, Dr. Burakowski is collaborating with Dr. Jessica Cantlon, who is doing response inhibition work with monkeys. Prior research predicts that the monkeys will demonstrate a similar response pattern to 3-year-olds. Findings consistent with this pattern will increase our understanding of cognitive abilities of our evolutionarily close neighbors and how functions in the brain evolved. Later in the semester, the students will work in small groups to conduct a similar comparative study of their own design, which will be approved both by their instructor and by Dr. Carver. Watch for their research questions an upcoming newsletter!

March 2022

The Emotions Game

Researchers from Carnegie Mellon’s CREATE Lab are preparing materials for their “MindfulNest” project, which is designed to support children’s emotion regulation skills in a typical prekindergarten classroom. In preparation for a broader study in the Pittsburgh region, Emily Hamner, Samantha Speer, and Mike Tasota will pilot a variety of emotion regulation measures from previous studies. In one, children hear short scenarios (e.g., a friend coming to play, a child purposely breaking a toy, a friend moving away, etc.) and label them with the emotion they would feel. If the emotion is negative, the child will be asked, “What would you do to feel better?” In the second task, researchers present brief puzzle tasks that mimic frustrating situations children might normally encounter. The child will be given either a toy locked in an unopenable box or an unsolvable puzzle, while the researchers monitor children’s emotion expression and coping strategies. If the child was given the toy locked in the unopenable box, after a few minutes the researcher will apologize for giving the child the wrong set of keys. The child will then be given the correct set of keys, which will allow them to open the box and play with the toy as promised. If the child has been given the unsolvable puzzle, the researcher will apologize for giving them a puzzle with mixed up pieces and allow them to play with a solvable puzzle. Understanding what children know about emotions and what strategies they use to help them handle frustrations will help us develop effective educational technologies.

April 2022

The Spelling Game

The best way to learn to spell is through practice! But practice is most helpful when a parent or teacher is available to give feedback. Lots of apps exist to address this problem - helping young readers practice spelling independently - but there has been little research on what the best design of these apps should be. Doctoral students from the Program in Interdisciplinary Education Research, Patience Stevens (Psychology) and Danny Weitekamp (Human Computer Interaction) have created an app that gives the child a word to spell, and then provides feedback on their spelling. They are interested in what kind of feedback is most useful: whole-word feedback (showing the entire correct spelling) or incremental feedback (just changing one letter to make the spelling more correct) so they have designed a study to compare the two approaches. Kindergartners will use their app to practice spelling for eight 10-minute sessions, spread over four weeks. They will measure children’s literacy skills before and after this intervention to see (1) if using the app improves their literacy skills and (2) which type of feedback leads to greater improvements in literacy skills. They hope that this study can improve the design of spelling apps to be as useful as possible to young readers!

The Dream Machine Game

The Communication and Learning lab at Carnegie Mellon University is still seeking 3 and 4-year-olds to participate in an online language learning study. They’ll send families a $10 Amazon gift card for participating. This is a 20-minute Zoom study where children will be asked to help fix the experimenter’s “dream machine” by naming pictures that appear on the screen.

If none of the available times work, or if anyone has any questions or concerns, please contact Megan Waller.

May 2022

The Story Time Games

Post-doctoral associate Catarina Vales and research associate Christine Wu, both from Dr. Anna Fisher’s lab, are examining whether children’s understanding of racial categories is malleable when influenced by children’s literature. Prior research shows that popular books for young children are more likely to include white characters and anthropomorphized nonhuman characters engaging in typical human behaviors (e.g., a dinosaur’s bedtime routine) than they are to include people of color as main characters. In this project, researchers want to tackle this disheartening reality by counteracting these statistics present in children's picture books.

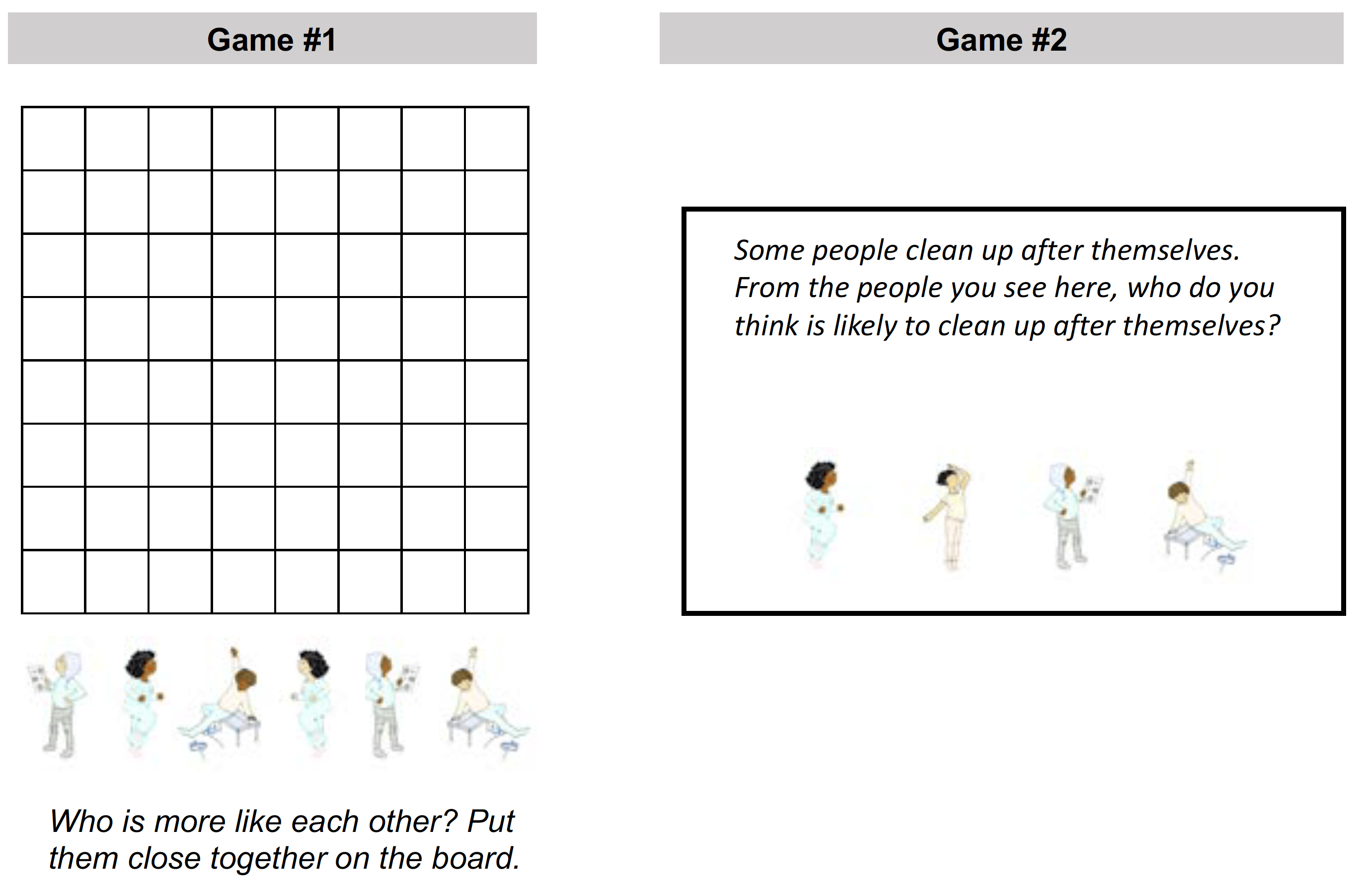

They selected commercially available picture books for children in which the main characters are people of color engaging in typical, everyday activities. Children attend daily story time sessions in small groups over the course of a week. To assess the effect of reading these books on children’s understanding of racial categories, the researchers ask children to complete two thinking games before and after this week-long story time experience. In the first game, children organize cards depicting dark- and lightskinned people on a game board such that people who are friends / people who are more like each other are placed close together. In the second game, children are asked which people (some dark- and some light-skinned) are more likely to have a certain trait (e.g., being a good friend; not cleaning up after themselves). The results of this study will help us understand if children’s experiences with inclusive picture books can be harnessed to decrease racial biases in children.

Last Call for the Dream Machine Game

The Communication and Learning lab at Carnegie Mellon University is still seeking 3 and 4-year-olds to participate in an online language learning study. They’ll send families a $10 Amazon gift card for participating. This is a 20-minute Zoom study where children will be asked to help fix the experimenter’s “dream machine” by naming pictures that appear on the screen.

If none of the available times work, or if anyone has any questions or concerns, please contact Megan Waller.