Scott Institute Hosts Energy Week, March 14-18

By Leigh Kish / 412-268-2902 / lkish@andrew.cmu.edu

With great power comes great responsibility.

No one knows that better than the 100+ renowned experts in Carnegie Mellon University's Wilton E. Scott Institute for Energy Innovation who are working to tackle one of the biggest challenges of the 21st century: making more efficient, affordable and sustainable energy.

To that end, they research and develop new products in energy storage and distribution, nuclear and shale gas development, smart buildings and cities, electric energy systems, and systems design optimization and technology and policy assessment.

"Energy is such a big problem, and really a problem for the century, both because we're dependent on it, and because energy is inseparable from climate change," said Jared L. Cohon, president emeritus and director of the Scott Institute, during an appearance on WPXI-TV's "Our Region's Business."

"Energy is such a big problem, and really a problem for the century, both because we're dependent on it, and because energy is inseparable from climate change," said Jared L. Cohon, president emeritus and director of the Scott Institute, during an appearance on WPXI-TV's "Our Region's Business."

Perhaps, then, it is better said: "With great power — to heat our homes, fuel our cars, and charge our smart phones — comes great responsibility."

The Scott Institute was launched in 2012 as a university-wide research initiative, pulling together faculty and their projects across technology, policy, integrated systems and behavioral science. The institute works with faculty and through departments and the colleges to identify new opportunities for collaborative research that build on the university's current strengths.

The Scott Institute's holistic approach to research and development, along with connections and resources from external partners, facilitates real-world solutions for energy problems.

One such solution is the non-toxic saltwater battery. Engineering Professor Jay Whitacre founded Aquion, a Pittsburgh area startup that manufactures his invention, the Aqueous Hybrid Ion (AHITM). The AHI is an environmentally friendly, sustainable and inexpensive battery that stores solar and wind energy. Residential customers and utility companies can use this non-toxic energy storage system to store wind and solar power for future use. Whitacre received the prestigious Lemelson-MIT prize for this invention.

"That's the whole idea of the Scott Institute. We support deep research that leads to new products and new ways of doing things to improve energy and help Pittsburgh and the nation," said Andy Gellman, professor of Chemical Engineering and co-director of the Scott Institute. Gellman created and leads the institute's seed grant program, now in its fourth year of providing some $500,000 per year to collaborative faculty groups to produce preliminary results before seeking major external support.

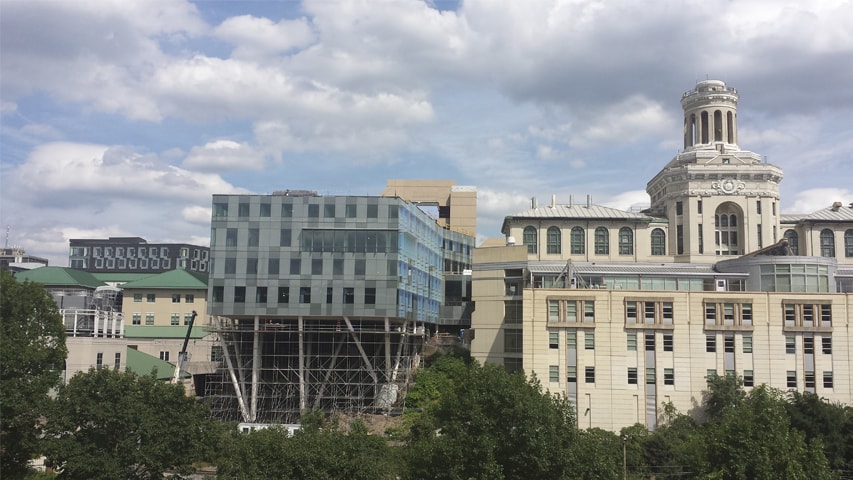

Location, Location, Location

A reality facing the Scott researchers is that energy issues tend to be complex without a simple solution that can be generally applied in all contexts.

For example: An electric car is not always better for the environment than a hybrid.

Ines Azevedo, an associate professor of Engineering and Public Policy, Jeremy Michalek, professor of Engineering and Public Policy and Mechanical Engineering, and Chris Hendrickson, University Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, together with Mili-Ann Tamayao, who earned her Ph.D. in engineering at CMU, looked critically at the carbon footprints of electric and hybrid vehicles, specifically the Leaf and Prius, across the U.S.

The study showed that these cars, though more emissions-friendly than their gasoline counterparts, can still result in significant emissions.

"Electricity is produced from different sources in different regions of the U.S. and at different times of day," Michalek said. "Different emissions are produced depending on where and when an electric vehicle is charged."

In some areas like the Midwest, coal-fired power plants, heavy on emissions, supply most of the power. In other parts of the country, the grid could be supplied by wind, solar, natural gas or coal-fired power depending on supply and demand.

As a result, a Midwestern hybrid can be a better choice than an electric car, and the reverse can be true in California.

For those not ready to move to a hybrid just yet, Stefan Bernhard, a professor of Chemistry and another Scott faculty member, might suggest a different type of solar power, this time using sunlight and a catalyst that speeds chemical processes to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. The hydrogen can then be used to fuel a vehicle, and it has less of an environmental impact than gasoline.

Location is not only important when charging an electric car; it also is important when considering where to put solar plants and wind farms. The greatest environmental benefits can be realized when this infrastructure is built in unexpected places.

"If our goal is to save the environment by reducing air pollution and carbon emissions, where you build those plants makes a difference," explains Azevedo in a Scott educational video. "While investing in wind farms and solar plants in California is helpful, the environmental benefits are substantially greater if you invest in those same plants in Western Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia. That is because electricity used in these regions is based on coal, while in California it is based on energy sources with less air pollution emissions, like natural gas."

This research is a start for informing consumers, policymakers and manufacturers in the U.S., but carbon emissions do not acknowledge borders. That is why it is essential to work toward global solutions, and Scott Institute faculty members are plugged into what's happening.

Climate on the World's Stage

This past December delegates from the world's 196 countries met in France for the United Nations Conference on Climate Change where they negotiated a pact limiting the increase in global temperature to two degrees Celsius from now until 2100.

Azevedo was one of the whopping 45,000 attendees who had the privilege of observing the open presentations and discussions.

"I thought it was very positive to see the resulting agreement include language that set a limit at 2 degrees Celsius," Azevedo said. "It is no small achievement to get all those parties together and for them to develop common language."

While the climate agreement sets the global limit of two degrees by 2100 - which is about 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit — the plan for doing so isn't specific. In fact, one of the focus areas for the Scott Institute is the development of methods to help policy makers identify specific pathways to a low-carbon energy future. Those pathways are likely to include the use of fossil fuels, especially natural gas, for many decades to come. The decisions we made today are likely to have long-lasting consequences.

"The infrastructure for natural gas that we are building today is the stuff that will be on the ground for the next 45 or 50 years. We're locked into that infrastructure," Azevedo said. "I would like to develop new frameworks that consider different circumstances, and that better track the consequences of today's decisions. We can make tools to help decision makers make wiser decisions before we're stuck."

What decision makers choose do is important for the climate and the economy. But what to do can be a moving target.

"In the 2000s, the U.S. was talking about installing natural gas import terminals. That's a multibillion dollar investment," Azevedo said. "Now, just 10 years later, we're talking about building export terminals, which is an equally large investment."

Power Play at Energy Week

With all that's going on in energy at CMU and in the world, the Scott Institute decided that the time is right to hold Carnegie Mellon's first Energy Week, March 14-18, open to everyone.

Each day has a theme: Monday's focus is research, Tuesday's focus is policy, Wednesday's focus is innovation, Thursday's focus is on education and Friday's is on field trip and energy workforce.

Participants can not only hear from top CMU researchers on the latest topics, but also participate in discussion on critical topics such as from what sources should Southwestern Pennsylvania get its electricity now and in the future? In addition, there will be roundtables on small- and medium-business energy entrepreneurship and innovation, industry energy efficiency, CMU education and research, and the region's energy workforce.

Keynote speakers include the deputy secretary of the U.S. Department of Energy, the director of the National Energy Technology Laboratory, the premier of South Australia, Pittsburgh's mayor, leadership from Barefoot College, which works with women in disadvantaged communities in India and Africa to build and maintain solar collectors, and a top energy storage expert from the Electric Power Research Institute.

Participants also will be able to visit CMU labs and research centers that focus on a wide variety of topics such as CMU's self-driving car, solar fuels and surface science to get a more in-depth look at what CMU's researchers are doing in energy. Other Energy Week activities focus on what CMU's students are doing in energy.

"We are hosting student competitions in research, technical innovation, policy, and even the arts for what we hope will be a lively event," said Deborah Stine, associate director of the Scott Institute and organizer of Energy Week.

Energy Week activities are not limited to those at CMU, but include the region as a whole.

"In the Pittsburgh area, energy is often assumed by outsiders to be limited to coal and shale gas. In reality, there are all sorts of exciting things going on in energy regionally," Stine said.

In addition, students from universities and colleges in Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia and Maryland will compete in the Allegheny CleanTech Competition for a $50,000 prize. CMU is the host for one of eight regional competitions. The three winners from the Allegheny competition will compete for an additional $50,000 prize at the national level. Last year's national winner, Hyliion, was from CMU.

More information on Energy Week is at http://www.cmuenergyweek.org. Registration for the entire slate events or daily passes are available.

By Friday of Energy Week, participants will have learned something new; students might have ideas for new career paths; and investors may have new technology to fund.

And CMU students and the Scott Institute experts? They'll be ready, and inspired, to continue their work on the next big thing.

Related links:

Energy Week

Scott Institute Video Series

Jay Whitacre awarded the $500,000 Lemelson-MIT Prize

The Energy Bite Radio Program