The Quiet Disappearance of Google’s Low Quality Content Advisory Banners

By Evan M. Williams

Image Generated using DALL-E

Keywords: google; content moderation; search engine; data void

Publication:

Robertson, R. E., Williams, E. M., & Carley, K. M. (2025). Data Voids and Warning Banners on Google Search. arXiv.org [link]

Investigating Google’s Content Advisories in Search

Content moderation policies from big tech companies shape the way people interact with information online. One approach that’s been widely studied is the use of warning labels, like the ones seen on Facebook and formerly Twitter, to help users gauge content accuracy. Many studies have shown that these labels can improve people’s ability to identify reliable information.

In 2020, Google introduced its own version of warning labels in Search, which it called content advisories. These banners appear at the top of search results to provide context about the quality and relevance of the information returned. Google announced these banners in a blog posts, but included no details about when or why they appear, what their limitations are, or how they can be improved.

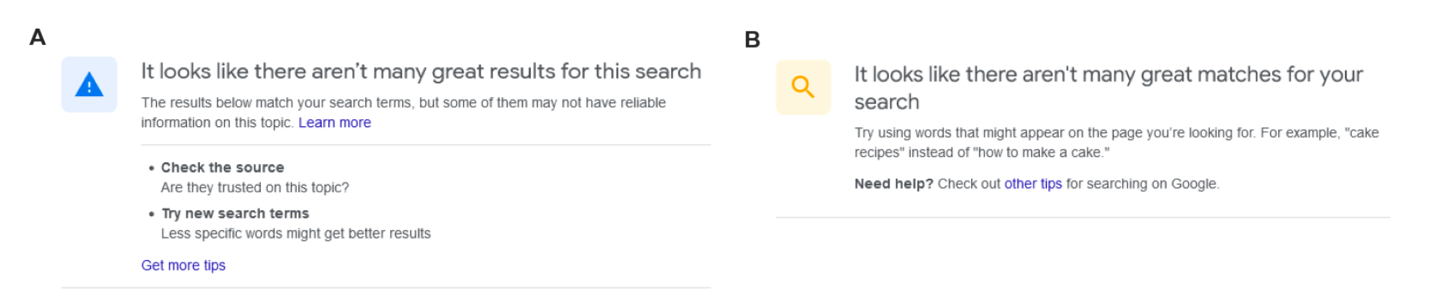

In our research, we focus on two specific types of advisory banners:

- Low-relevance banners (Figure 1, panel B), which warn users when Google doesn’t have highly relevant results for a search.

- Low-quality banners (Figure 1, panel A), which caution users that the available search results may not contain reliable information.

To improve Google’s bannering system, we develop a graph neural network designed to enhance Google's bannering methodology, making these advisories more precise and effective. Surprisingly, in August 2024, while we were conducting this research, Google appears to have discontinued its low-quality banners without any announcement.

Figure 1. (A) Low-quality banners which warn users when search results may contain misinformation, (B) Low-relevance banners warn users when search results are not relevant

Mapping Google’s Content Advisories at Scale

To uncover how Google deploys content advisories, we started with a dataset of 1.4 million search directives—queries designed to prompt online searches, such as “look up ‘Chemtrails’ on Google”—extracted from prior research. These queries span topics like news, health, and politics, and they help identify data voids, where search rankings are dominated by irrelevant or low-quality results.

We then gathered 23.9 million search results from Google, analyzing how often content advisories appeared. Out of all queries tested, 14.4K (1%) triggered a content moderation banner:

To track consistency, we conducted three large-scale crawls—in October 2023 (Crawl-1), March 2024 (Crawl-2), and September 2024 (Crawl-3)—and repeated the collection of 301 low-quality banners 73 times at ~4.5-hour intervals. This allowed us to observe how often these banners appeared and whether they persisted over time.

Findings

1. What Triggers Google’s Content Advisories?

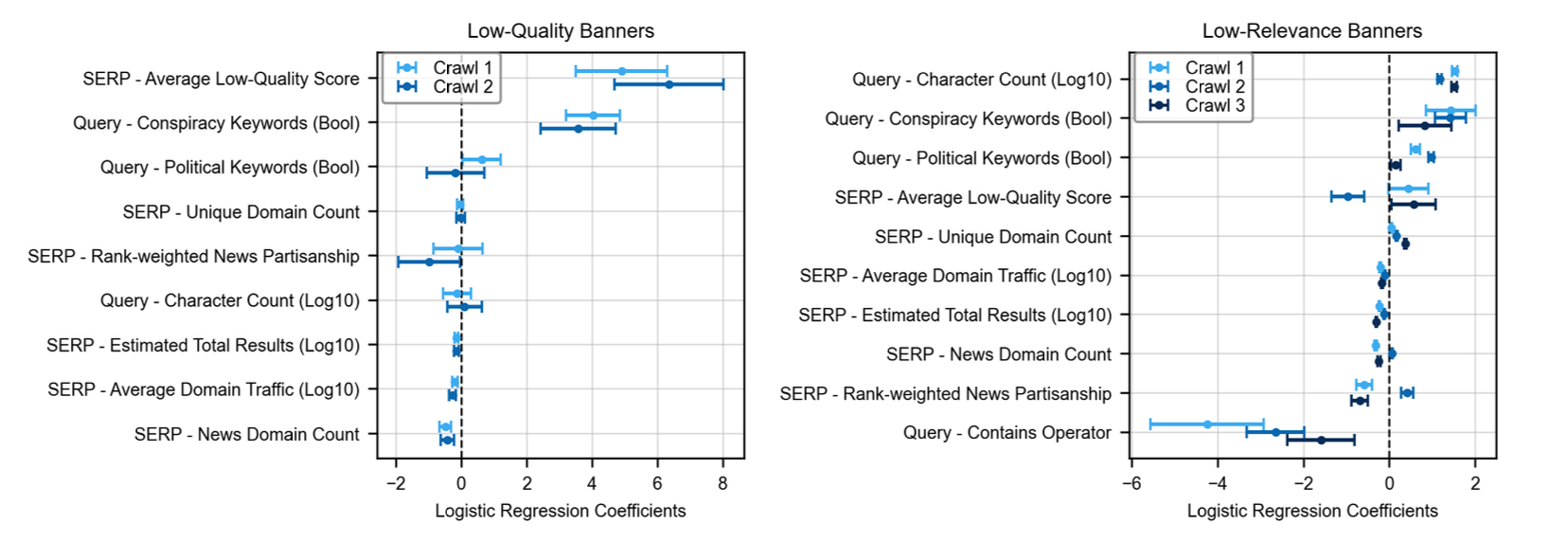

Figure 2. Logistic Regressions showing feature associations for queries and SERPs with low-quality (left) and low-relevance (right) banners

To understand what factors lead to Google displaying content advisories, we ran logistic regression analyses on search queries and results. The findings reveal some clear patterns (Figure 2):

- Low-quality banners are strongly associated with search results containing links to low-reliability domains.

- Low-relevance banners tend to appear for searches with longer character counts.

- Both types of banners are more likely to show up when queries contain conspiratorial keyphrases.

One particularly interesting discovery: low-quality banners never appeared when the "site:" operator was used, even for highly unreliable sources. For example, searches like "ginko site:naturalnews[.]com" or "site:stormfront[.]org 'sleepy eyes'"—which target known misinformation-heavy domains—didn’t trigger a warning. This suggests Google’s bannering system is evadable; as we’re looking at search directives.

2. Low-Quality Banners Appear Inconsistently Over Time

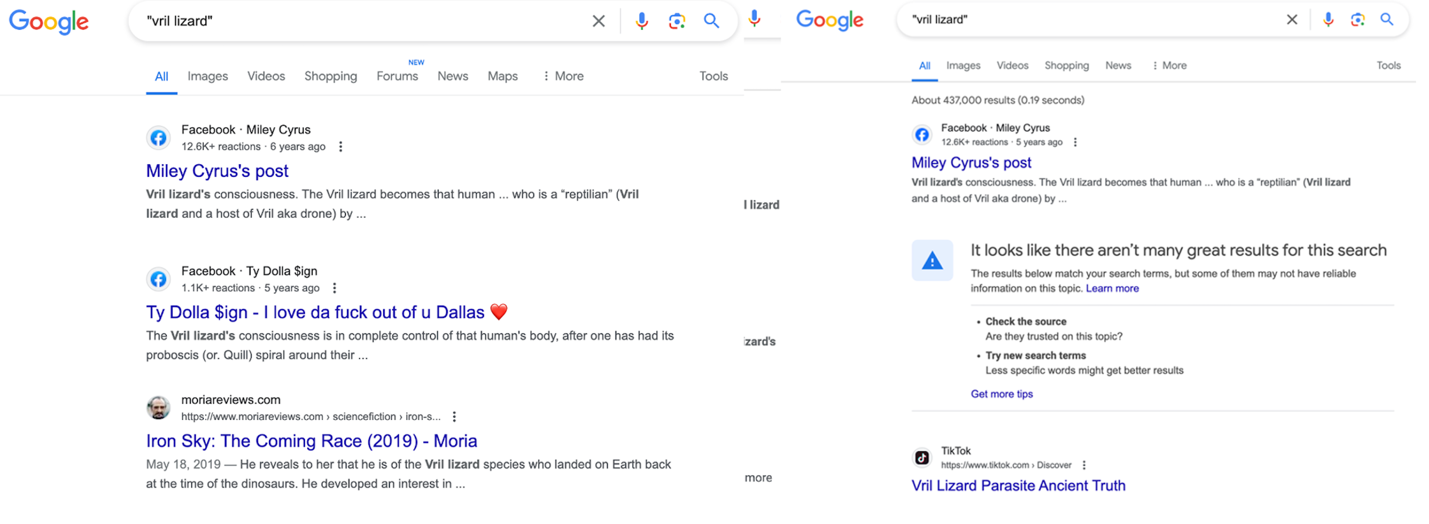

Figure 3. Screenshot of SERPs for “vril lizard” taken within hours of one another. Despite the identical query, only one returns a quality banner.

One of the most striking findings in our analysis is that low-quality banners are unstable, sometimes appearing and sometimes not—even for the exact same query. Figure 3 illustrates this inconsistency with two screenshots of search results for "vril lizard"—mythical lizards that allegedly control the minds of various politicians and celebrities—taken just hours apart. In one instance, Google displayed a low-quality banner; in the other, it did not.

Across 73 repeated collections of the 301 queries that initially triggered a low-quality banner, we found that 90 queries fluctuated between having a banner and not. This suggests that banner placement is highly dependent on changes in the search results themselves.

To better understand this, we tried reverse-engineering the conditions that trigger a banner. We found that no individual URLs, URL pairs, URL pairs conditioned on rank, or URL triplets could fully explain all banner appearances.

3. Using Graph Neural Networks to Predict Low-Quality Banners

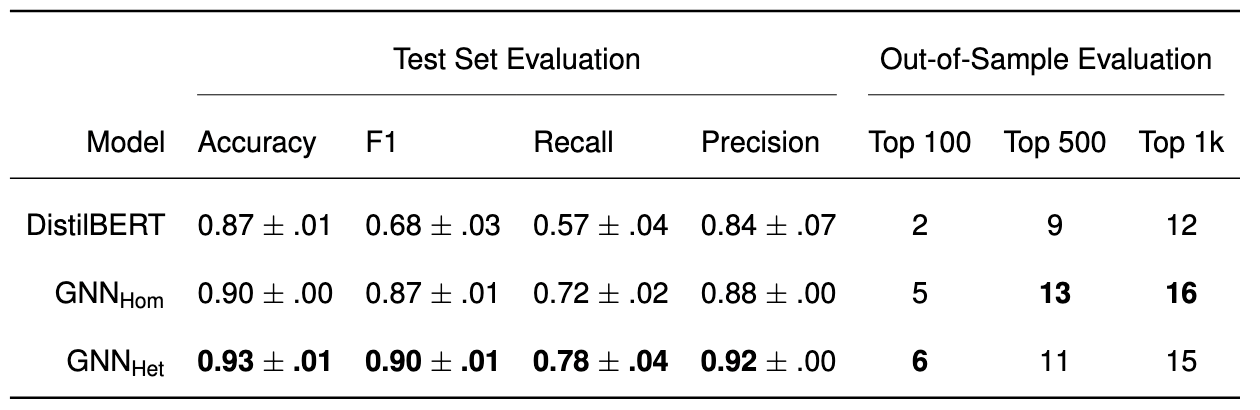

Table 1: Test Set and Out-of-Sample Evaluations

Table 1: Test Set and Out-of-Sample Evaluations

Building on our analysis of Google’s low-quality banners, we explored whether deep learning models could help identify data voids and improve the detection of queries likely to trigger low-quality advisories. To do this, we developed and tested three models:

- A homogeneous Graph Neural Network (GNN)

- A heterogeneous GNN, trained on a bipartite graph linking queries to domains

- A fine-tuned DistilBERT model, trained on query text

Unlike traditional approaches, our models rely only on content from SERP pages—they do not use domain-level features or external reliability annotations.

We evaluated model performance in two ways:

- Hold-out set evaluation (Table 1, left) to test in-sample accuracy.

- Out-of-sample evaluation (Table 1, right), where we checked if our models could predict queries that received low-quality banners in Crawl-2 but not in Crawl-1.

The results were promising. Among the heterogeneous GNN’s 100 most confident low-quality banner predictions, 6 received a quality banner in Crawl-2, despite not having one in Crawl-1. This suggests that graph-based models can effectively detect signals that align with Google’s moderation decisions. Further evaluations and analysis can be found in our paper.

4. Did Google Discontinue Low-Quality Banners in August 2024?

In August 2024, we conducted several experiments to assess whether the presence of low-quality banners remained stable across different types of queries. To our surprise, we found that not a single query returned a low-quality banner—despite testing on multiple computers in different states across the US. This finding was replicated in our September 2024 crawl (Crawl-3), where we again observed no low-quality banners.

Our analysis ruled out two hypothetical explanations for the disappearance of banners:

- We show that low-quality banners were likely not subsumed by low-relevance banners

- We show that Google’s algorithm had improved so much that banners were no longer needed.

Google made no announcement regarding the discontinuation of these banners, so this is surprising, particularly given that research has shown that warning banners are valuable tools to help users identify unreliable content. We do not know why Google removed these banners.

Content Moderation Should be Transparent!

In this study, we developed new methods to surface, evaluate, and predict the use of warning banners in web search engines—and put them to the test on Google Search. Our goal was to understand how often data voids occur and how Google’s moderation system responds to them.

After collecting data over several months, we found that Google’s low-quality banners were relatively rare and governed by inconsistent, often easily bypassed rules. Even more surprising, by August 2024, these banners appeared to be quietly discontinued We couldn’t explain this disappearance through improvements in domain quality or replacement with a different type of banner. This work highlights the need for transparency in content moderation practices of large platforms.