August 07, 2023

Where Online Meets Offline in an Infodemic

Covid-19 pandemic; face masks; bots; online misinformation

The Covid-19 pandemic wreaked havoc all around the world. Infections spread at unprecedented rates in many nations, and many governments struggled to put a stop to them.

Face masks emerged as an important public health tool given their relatively low cost but high effectiveness at mitigating disease transmission. Yet in many places like the United States, they became highly politicized. While public health research had shown that mandating the wearing of face masks could make a significant dent on “flattening the curve”, they also produced backlash among polarized societies.

In our highly digitalized world, these dynamics did not exclusively occur offline. Online misinformation proliferated in line with controversies surrounding face masks. Automated bot accounts were likewise used to manipulate online conversations about them. Moreover, as people talked about face masks on social media, they were likewise exposed to the views of others, which may have in turn influenced them.

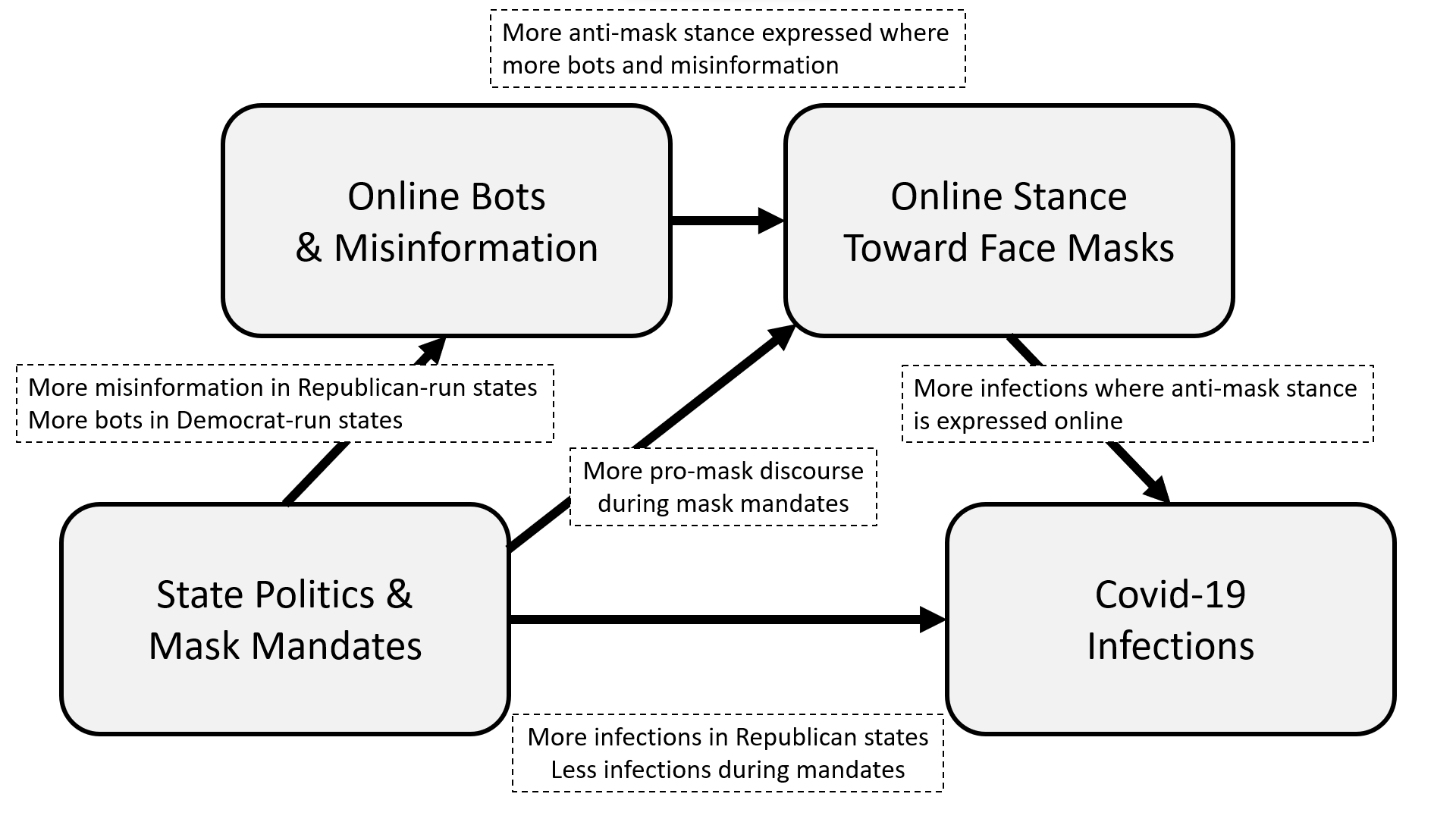

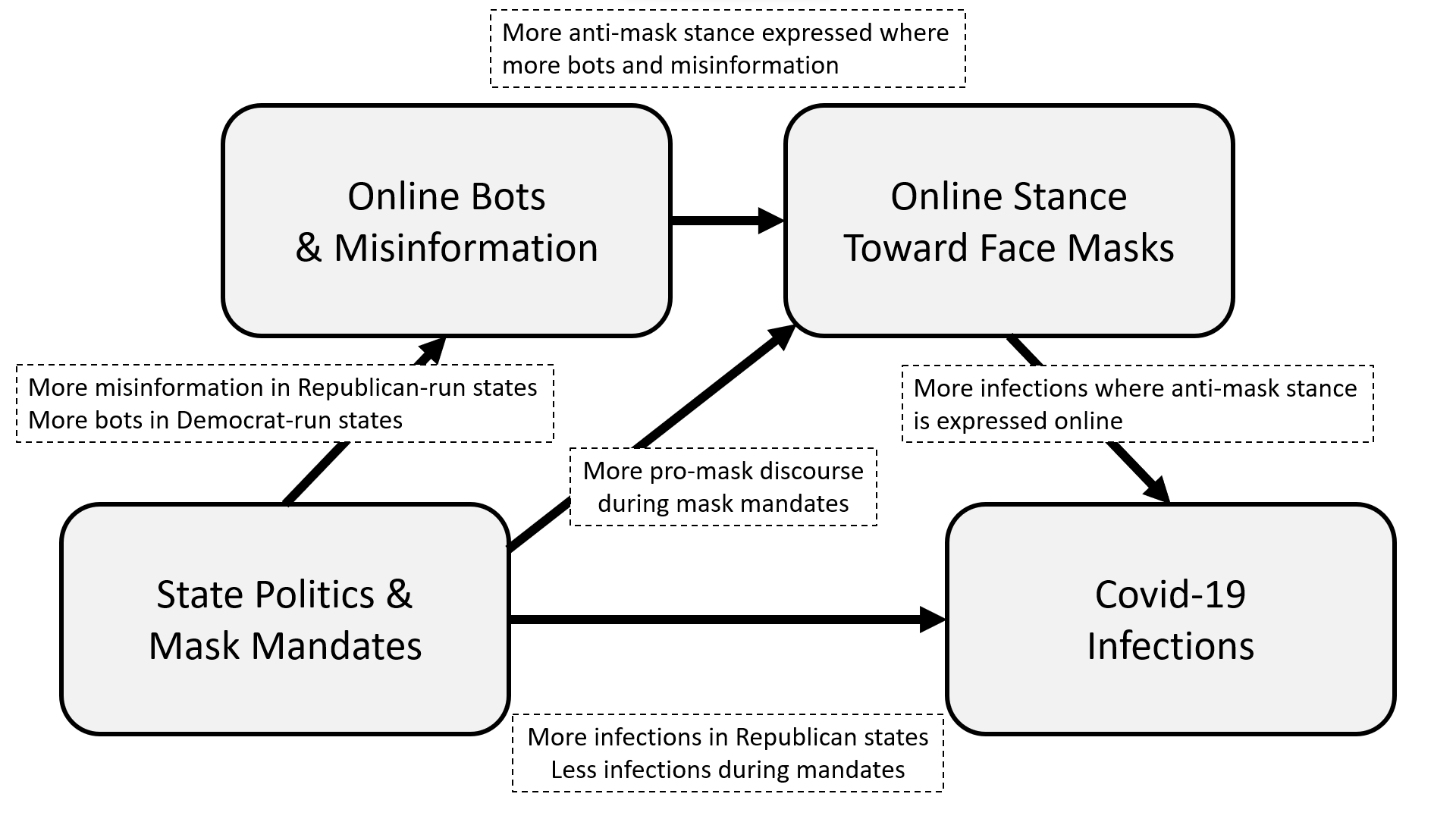

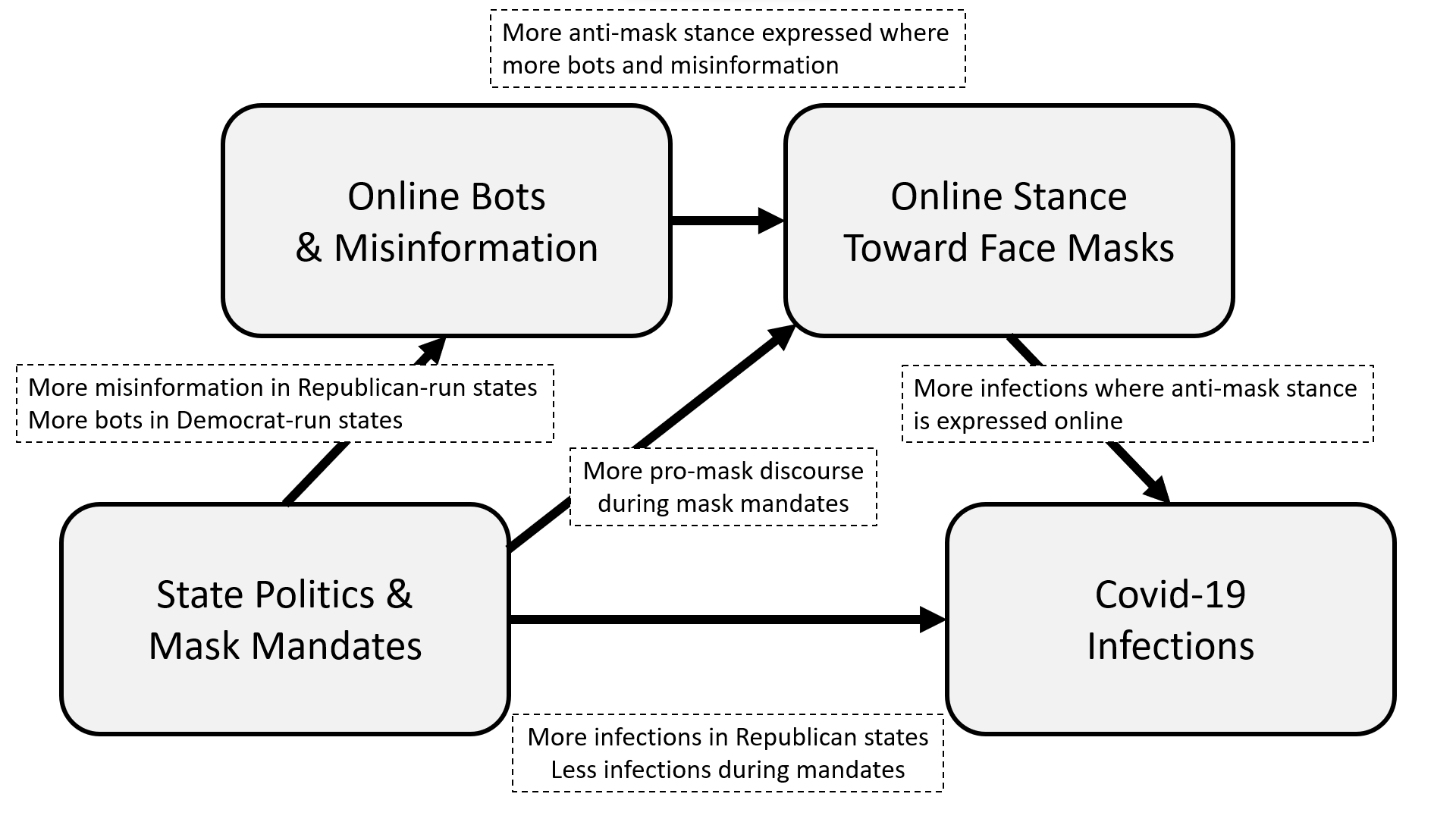

Our research investigates how these online and offline dynamics worked together in the United States. We aimed to quantify how much online chatter about face masks related with both offline contexts of state politics and mandates, as well as eventual offline outcomes of actual mask-wearing behaviors and further Covid-19 infections.

Online Chatter Matters

To undertake this research, we combined Twitter data from the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic with offline data on state governors, mask mandates, and daily recorded Covid-19 cases.

Using a series of our research group’s computational tools, we associated each tweet with: its stance toward face masks, its user’s approximate location (e.g., which U.S. state), the likelihood that it was produced by a bot, and whether it contained a link to a low-credibility website.

From this data, several things became abundantly apparent. First, whenever mask mandates were announced in a given state, tweets about face masks spiked significantly. This was an enduring effect that was consistent across U.S. states regardless of the state governor’s political party. In other words, all around the country, online conversations were reacting to offline realities.

More importantly, however, we made a second observation: whenever online conversations became more pro-mask or anti-mask, future Covid-19 infections reacted accordingly. More pro-mask online conversations were related to fewer Covid-19 infections some weeks later, whereas more anti-mask online conversations were linked with more Covid-19 infections in the same time frame.

For dates when actual mask-wearing data was available, we further determined that the stance of online conversations was related to future Covid-19 infections specifically through association with behavioral changes. When people in a state were more pro-mask online, they were also more likely to wear masks and thus see fewer infections later on. Conversely, when a state had more anti-mask online conversations, they were less likely to wear masks and thus see more infections later on.

Online Influences and Offline Politics

These online-offline dynamics did not take place without attempts to manipulate them.

By measuring each account’s level of automated activity and links to low-credibility information, we observed consistent effects in all states. Wherever there were more bots and low-credibility information, anti-mask stance rose. In line with the previously observed effects, that means that bots and online misinformation were also associated with lower rates of actual mask-wearing and higher rates of Covid-19 infection a few weeks later.

Yet while these effects were consistent for all U.S. states, the prevalence of bots and lowcredibility information in online conversations actually reflected offline political cleavages. More specifically, low-credibility information tended to spread in states that were run by Republican governors. On the other hand, bots tended to be most active in states that were governed by Democrats.

What this shows is that different types of online harms may be more active in different contexts. It also suggests that different types of demographics may be vulnerable to different forms of manipulation, especially in crises like the Covid-19 pandemic.

Social Cybersecurity Implications for Infodemics

While this analysis is not causal, it does reveal crucial online-offline associations that will be relevant to researchers, practitioners, and policymakers. It underscores the value of social cybersecurity research in contexts of upheaval and emergency as the online and offline worlds continue to be intertwined in contemporary societies globally.

When governments implement interventions during crisis, especially polarizing ones, it is worth having meaningful systems in place for monitoring online discussion. Collective public behaviors can be reflected in online conversations, and indeed, these online conversations can in turn help predict how offline behaviors are prone to change with time.

Furthermore, with the sustained threat of online harms in the form of bots and misinformation, it is crucial that they not be considered in a political vacuum. The types of online interventions required in different settings can vary, since different types of manipulation target different people. Resilience to these online harms must therefore be cultivated not with one-size-fits-all solutions, but with an integrated and contextually sensitive approach.