Hunting COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories

By J.D. Moffitt & Catherine King

Direct link to paper, published September 06, 2021: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/20563051211043212

tags: conspiracy theories; disinformation; natural language processing; social media

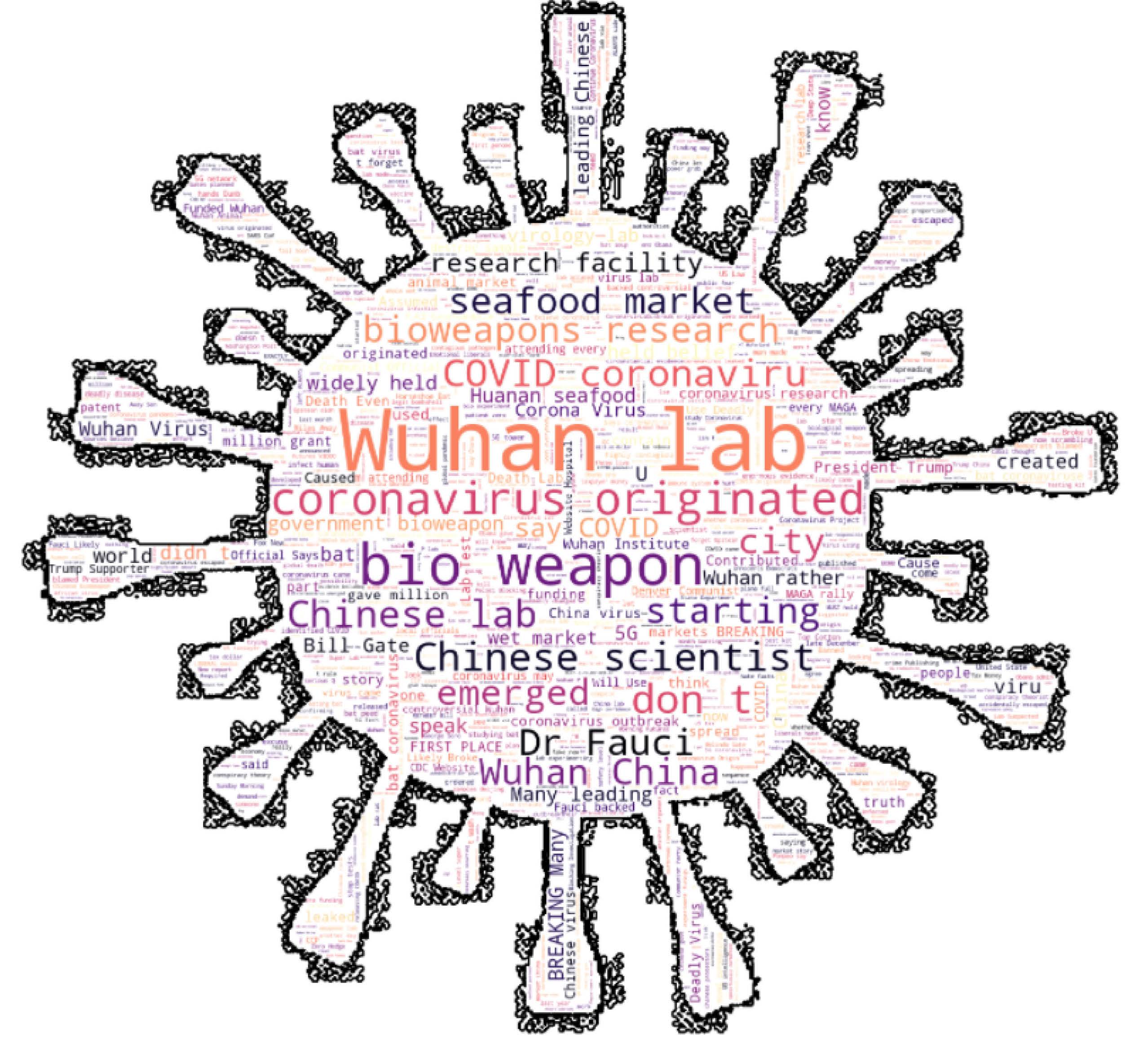

Image credit: J.D. Moffitt, word cloud generated from tweets classified as conspiracy

Conspiracy theories often serve as a coping mechanism to explain complex situations, which may explain why they are especially appealing to people in times of crisis. People who believe conspiracy theories are not limited to recluses living in basements, wearing tin foil hats; they could also be your friends, families, or neighbors.

The COVID-19 pandemic created a perfect storm of panic, uncertainty, and isolation that forged an environment for conspiracy theories to thrive. In 2020, the Pew Research Center reported that 36% of people who heard the conspiracy theory that the COVID-19 outbreak was planned thought that it was ‘probably’ or ‘definitely’ true. Belief in COVID-19 conspiracy theories was also shown to be correlated with taking fewer precautions like handwashing and physical distancing.

Why do people believe in conspiracy theories?

Critical motivators for believing in conspiracy theories include, but are not limited to, a desire for information, individual control over one’s world, and a way to maintain a positive self-image (identity) for an individual or in-group. Conspiratorial individuals often believe in multiple conspiracy theories at once, including seemingly incompatible ones like the theory that Osama Bin Laden was already dead when his compound was raided, but also he’s still alive somewhere.

Motivators alone are not enough for conspiracy theories to truly take hold; communicating them is another significant factor. Previous research shows three key dimensions for a conspiracy: the stick, the spread, and the action. Said more plainly, a conspiracy theory is a success if

- The message/story resonates with a core group of passionate individuals (the stick)

- The core group compellingly amplifies the message to attract others while deflecting detractors (the spread)

- The message allows for participation and sometimes directed action from the followers (the action).

What impact do conspiracy theories have?

The rise of social media and alternative news ecosystems has allowed fringe ideas to garner greater reach, allowing conspiracy theories to go more mainstream. As recently as last year, we’ve seen online conspiracy theories lead to real-world violence; Pizza-gate, the destruction of 5G towers during the pandemic, and the 2021 U.S. Capitol Attack.

Not all conspiracy theories result in negative real-world consequences. Most Americans believe in at least one conspiracy theory, with over half of Americans believing the conspiracy theory that Lee Harvey Oswald didn't act alone in John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Many conspiracy theories, including those surrounding JFK’s assassination and 9/11 truthers, do not lead to violence because they have no “action” associated with the conspiracy message. However, conspiracy theories that surround cherished values like democracy are more likely to inspire passionate supporters who engage in action. For example, individuals who believed in voter fraud conspiracy theories stormed the U.S. Capitol building, as that was a direct action in the message.. Those who believe in JFK conspiracy theories have no such plausible action.

Individuals who believe in COVID-19 conspiracy theories do have actions they can take, such as not wearing masks, social distancing, or getting vaccinated. Because health-related conspiracy theories can impact behavior in a pandemic, it is crucial to study their spread and reach in an effort to develop effective mitigation strategies.

Can conspiracy theories on social media be detected?

In our quest to understand conspiracy theories present in COVID-19 related discussions on Twitter, we focused specifically on origin theories of the virus. We structured our research around three main questions:

- Can we rapidly and accurately identify conspiracy theory tweets related to COVID-19?

- How do users behind conspiracy theory tweets differ from non-conspiracy users?

- How are the tweets that carry conspiracy theories propagating through the extensive COVID-19 discussion?

To classify tweets as conspiracy-related or not, we used a large, pre-trained language model to transform our tweet text into numerical form for use in classification models. Language models learn a statistical understanding of the data they train on; by picking a model trained on COVID-19 Tweets, we could feed our text classifier better-contextualized representation rather than a bag-of-words or even Bert-base model representations. We then trained a multi-layer perceptron model for a binary text classification task. In addition to the metadata provided by the Twitter API, we enriched our data with predictions of whether the tweet author is a bot or not, and location and social identity predictions for tweet authors. After model training was completed, we deployed it to classify over 1.5 million COVID-19 related tweets.

What do 1.5 million COVID-19 tweets tell you about conspiracy theories?

First, we were surprised by the success language models and neural networks had in this space. Our BERT-based model was able to quickly and accurately classify our corpus of tweets as conspiracy theories or not. This research shows that these types of NLP models are scalable and could be used for other applications including other mis-/dis-information-related problems.

Our critical findings

- Celebrities and regular user identities comprised a higher fraction of those promoting conspiracy theories than other user identities like journalists, government organizations, or sports figures.

- Accounts in the conspiracy theory group were more likely to be bots than accounts in the non-conspiracy theory group.

- United States-based users did a disproportionate amount of the spreading of conspiracy theories.

- When comparing bot deployment strategies between conspiracy and non-conspiracy groups, conspiracy bots focused relatively less of their effort on amplification and instead focused on community building through mentions. It appears that bots may be used to facilitate the 'stick' and 'spread' dimensions of a successful conspiracy theory dispersion.

Finally, we were surprised at the concentrated linkage to low credibility/editorial review sources through URLs. We found that conspiracy-related tweets contained URLs to a less diverse set of internet domains. On average, those domains had lower credibility scores than URLs found in non-conspiracy-related tweets. This exciting finding inspired our current research to map and explore the URL/domain ecosystem that helped facilitate the spread of COVID-19 conspiracy theories.

Overall, this study was extremely rewarding. We gathered a greater appreciation for conspiracy theories and the potential impacts they can have on society. Conspiracy theories have shown great disruptive utility in the information space throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and the recent United States election. Research focused on early detection, and a more generalizable classification of conspiracy theories would be beneficial to the study of disinformation and the field of Social-cybersecurity.