Does Gender Influence How Presidential Candidates are Treated on Social Media?

By Catherine King

Associated Publication:

- King, C., Carley, K.M. Gender dynamics on Twitter during the 2020 U.S. Democratic presidential primary.Social Network Analysis and Mining. 13, 50 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-023-01045-4

Tags: abusive language, 2020 U.S. Election, social media analysis

The 2020 U.S. Democratic presidential primary was the most diverse in United States history.

It also marked the first time that more than one woman, including Senators Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar, made it to a primary debate for a major party [1]. The primary also included the first openly gay candidate, Pete Buttigieg, and several candidates of color, including then-Senator Kamala Harris.

Gender representation in U.S. politics has grown over the last few decades, with women accounting for approximately 25% of Congress in 2020 [2]. However, there has yet to be a female or openly gay president.

There are several possible barriers to a woman becoming president. Prior research has shown that while women are just as likely to win a political race as men, this is most likely due to women typically having higher qualifications before deciding to run. Comparing men and women of equal qualification leads to a 3% “gender penalty” at the ballot box [3]. Some of this penalty may come from implicit bias about presumed gender roles – for example, ambition is seen as a positive trait for male candidates, but a negative trait for female ones [4]. At the presidential level, these gender roles may carry more weight in the minds of voters. Other research suggests this 3% penalty may also be due in part to the female candidates receiving less traditional media coverage [5].

Recent research on social media has suggested something similar – when several high-profile women announced their run for president in 2019 (Kamala Harris, Elizabeth Warren, and Amy Klobuchar), their social media coverage tended to be more negative, more about their identity, and they received more fake news and far-right attacks than the men who announced their run for president (Pete Buttigieg, Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders) [5].

This research seeks to investigate if female presidential candidates were treated differently by those on social media than male candidates. Our primary research questions are:

- How did the amount of Twitter conversations surrounding each main candidate change over time?

- Were the female candidates treated differently, by getting more abusive language and gender slurs?

- Who is behind the abusive and sexist language on Twitter against these candidates – bots or regular users?

We collected data on Twitter from December 1st, 2019 – April 28th, 2020.

We used this range so that we had data spanning several weeks before the first primary election (Iowa, Feb 3rd, 2020), during the competitive phase of the primary (Biden became presumptive nominee by March 3rd, with most candidates dropped out by end of March), and post-primary data through the end of April.

We then split the data into five datasets, one for each of the top candidates: Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Pete Buttigieg, and Amy Klobuchar. These candidates were selected because they were earned delegates in the first four primary states and participated in all the pre-primary debates. Any tweets that mentioned or discussed Biden were included in the Biden dataset, any tweet that discussed Sanders in the Sanders dataset, and so forth.

FINDINGS

- The most popular candidates nationally were discussed the most on Twitter and faced the most abuse.

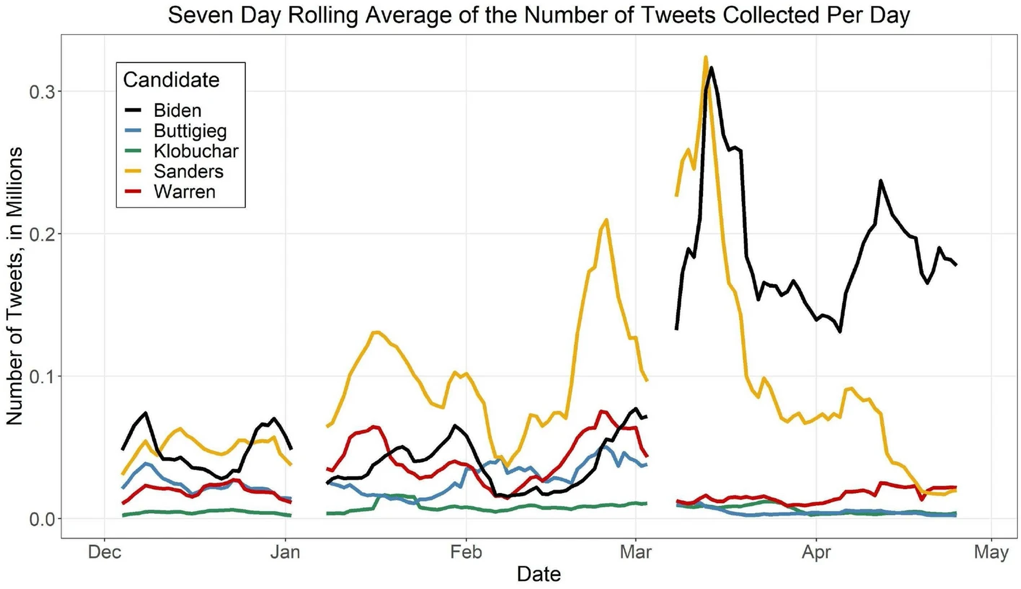

To answer the first research question, we looked at the size of each candidate’s dataset. The graph below shows the number of tweets collected for each candidate in the time frame. The more popular candidates (Biden and especially Sanders) dominated the conversation until around mid-March when Biden became the presumptive nominee and much of the conversation switched to him. Data gaps are due to the data collection stream going down on certain days.

While Twitter is not necessarily representative of the American voting public, it did reflect current events and election outcomes.

Next, we calculated how many tweets in each candidate’s dataset contained at least one abusive word using NetMapper [6]. We found that not only did Biden receive substantially more abusive tweets than others, but also a higher fraction of his total tweets were abusive (4.1%). We compared the fraction of tweets to better compare Biden to less popular candidates.

|

Candidates |

Total Number of Abusive Tweets |

Percent of Total Tweets that were Abusive |

|

Joe Biden |

576,499 |

4.1% |

|

Bernie Sanders |

421,000 |

3.3% |

|

Elizabeth Warren |

148,627 |

3.7% |

|

Pete Buttigieg |

98,042 |

3.6% |

|

Amy Klobuchar |

19,319 |

2.0% |

2. Women were more likely to be targeted with gender slurs, and slurs that typically describe women were used much more frequently than male slurs in general

Next, we turn to research question 2 and investigated if the women candidates were treated differently on Twitter. We searched the tweets for female gendered-based slurs: “b*tch, c*nt, s*ut, wh*re, sk*nk, cow” (selected based on a literature review). The women had a higher fraction of their abusive tweets as gendered. Almost 2.5% of abusive tweets directed at Klobuchar were gendered.

|

Candidates |

Total Number of Tweets with Female Gender Slurs |

Percent of Abusive Tweets with Female Gender Slurs |

|

Joe Biden |

11,094 |

1.92 |

|

Bernie Sanders |

8804 |

2.09 |

|

Elizabeth Warren |

3198 |

2.15 |

|

Pete Buttigieg |

1414 |

1.44 |

|

Amy Klobuchar |

488 |

2.53 |

Also, in every candidate’s data set, the frequency of the top female slur (“b*tch”) was always more than the top two male slurs combined (“d*ck”, “b*stard”)

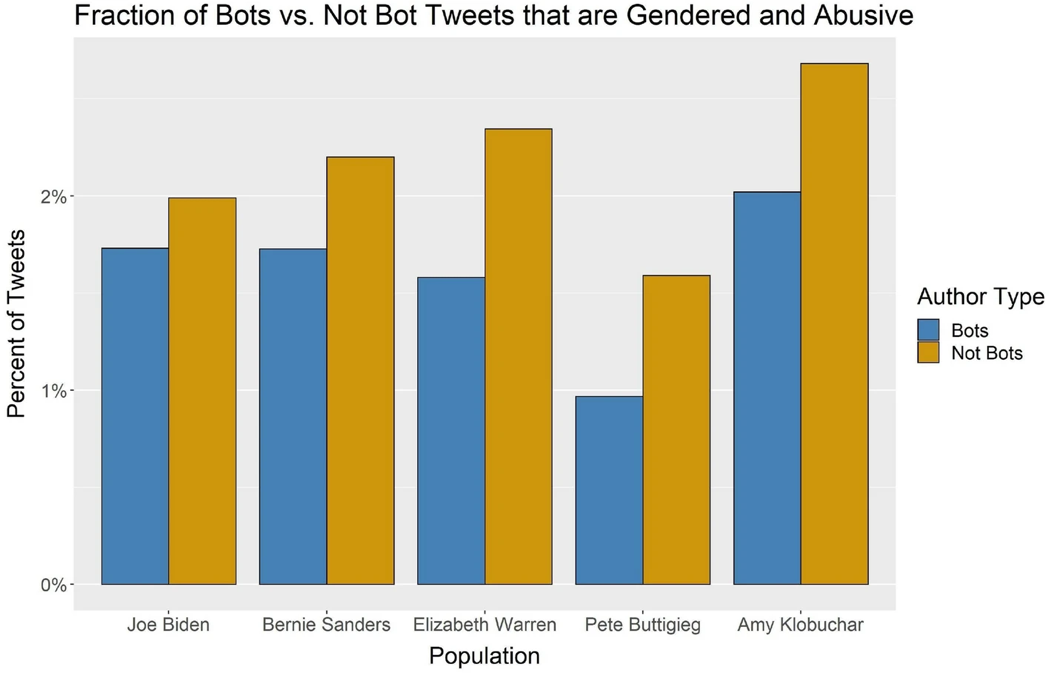

3. Normal users were more likely to use abusive words or gender slurs than bot accounts

The graph below shows the percent of abusive tweets from bot and not bot accounts that used female-gendered language. We found that for all candidates, normal users were more likely to use abusive words. Bots were determined by using the BotHunter algorithm [7]. Any account with a bot probability score of 0.7 or higher was classified as a bot in this graph.

IMPLICATIONS

Although there has been progress to increase representation in politics, women may still be at a disadvantage when running for president. This work primarily examines the 2020 U.S. Democratic presidential campaign, but it also sheds light on a larger problem that women confront in other elections, both in the U.S. and abroad. It is crucial that as a society we bring awareness to any unequal treatment of specific types of candidates, whether that be in the media or in discussions amongst voters.

References

[1] Zhou L (2019) It’s the first time in US history that more than one woman candidate will be on the presidential debate stage. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2019/6/26/18716212/democratic-debatesdiversity-elizabeth-warren-kamala-harris-amy-klobuchar.

[2] Women in the U.S. Congress (2020) Center for American Women and Politics. https://www.cawp.rutgers.edu/women-us-congress-2020.

[3] Fulton SA (2013) When gender matters: macro-dynamics and micro-mechanisms. Polit Behav 36(3):605–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9245-1

[4] Conroy M, Martin DJ, Nalder KL (2020) Gender, sex, and the role of stereotypes in evaluations of Hillary Clinton and the 2016 presidential candidates. J Women, Polit Policy 41:194–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554477X.2020.1731280

[5] Oates S, Gurevich O, Walker C, Di Meco L (2019) Running while female: using AI to track how Twitter commentary disadvantages women in the 2020 U.S. primaries. SSRN Scholarly Paper No. ID 3444200. Social Science Research Network, Rochester. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3444200.

[6] https://netanomics.com/netmapper/

[7] Beskow DM, Carley KM (2020) You are known by your friends: leveraging network metrics for bot detection in Twitter. In: Tayebi MA, Glässer U, Skillicorn DB (eds) Open source intelligence and cyber crime: social media analytics. Springer, Cham, pp 53–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41251-73