Increasing Crops Won't Ease Hunger if Supply Chains Don't Keep Pace

Pilot Use of HERMES Supply-Chain Software Reveals Need to Analyze Food Delivery Networks

We might think that, if you want to feed more people in areas with food insecurity, you can just grow more food. But it isn't that simple.

A team led by Public Health Computational, Informatics, and Operations Research (PHICOR), at the time based at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and currently based at City University of New York (CUNY), used the HERMES supply chain software developed by scientists there and at the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center (PSC) to show that increases in vegetable production in Odisha, a state in India, wouldn't increase the supply if the delivery network can't move the veggies before they spoil. The initial study is a successful proof-of-concept for using HERMES, previously employed to simulate vaccine and other medical supply chains, to study food availability.

The number of people facing serious food insecurity increased from 282 million at the end of 2021 to 345 million in 2022. At the same time, in much of the world and in wealthier economies, diets that are high in sugars and fats have led to an epidemic of obesity, diabetes and heart disease.

There's a simple-minded solution: everybody needs to eat more vegetables. But making that happen is difficult. Getting people in developed economies to eat more vegetables is one problem. Even in places where more vegetables would be welcome, getting them to the people who need them is trickier than it sounds. And just as critical to people being fed is farmers getting paid, so they can afford to keep growing. Spoilage en route can affect both goals.

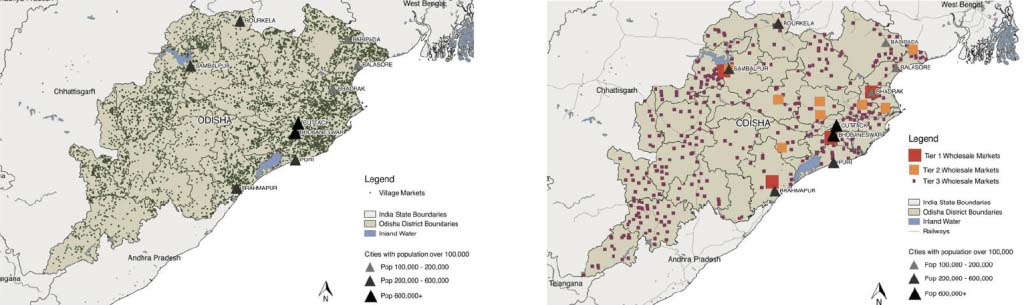

Village market locations (left) and wholesale market locations (right) in the Indian state of Odisha. Getting vegetables from farms to wholesale locations to more than 5,000 village markets proved a challenge in translating increased vegetable production to more veggies on people's dinner plates. From Spiker ML et al. When increasing vegetable production may worsen food availability gaps: A simulation model in India. Food Policy 116(2023):102416-102430.

Marie Spiker of the University of Washington School of Public Health, then a graduate student in Bruce Y. Lee's PHICOR research team at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, wanted to know whether simply growing more vegetables would help ease food shortages in Odisha, a state in India.

"In the world of nutrition and food security, we're asking questions about 'do we have enough food' — not just any food, but nutritious, healthy food to meet everyone's needs," Spiker said. "The conversation tends to focus on either end of the supply chain — food production and food consumption — but there is this whole 'missing middle,' which is the supply chain. The supply chain becomes really important when we're talking about perishable foods."

To tackle this problem, they worked with Joel Welling, senior scientific specialist at PSC, employing the HERMES simulation software that Lee, now at the City University of New York, developed in collaboration with scientists at PSC on the center's Bridges-2 supercomputer.

Scientists at Hopkins, the University of Pittsburgh, and PSC developed HERMES to study how supply chains affect the delivery of goods from where they're made to where they're needed. To do this, it simulates the entire chain of delivery, from warehouses to regional centers to local communities. In particular, it takes into consideration chokepoints, like the availability of storage at each location or of motorcycles to make the final steps in delivery to remote rural locations.

"[When we used HERMES to create] models of vaccine supply chains ... we found in Niger a number of bottlenecks. There was not enough transport, not enough capacity," Lee said. "This was a common problem in a lot of supply chain designs in the 1970s ... Lots of countries could benefit from having a tool that could assess their supply chains."

HERMES revealed weak points in vaccine delivery in the African nations of Niger and Benin. This analysis enabled the HERMES Logistics Modeling Team to recommend changes to the Benin government that reduced child mortality, even while lowering costs. It also showed that aerial drones could improve vaccine delivery and decrease costs in low- and middle-income countries.

While the group had used HERMES mostly to analyze the movement of medical supplies, the software could analyze any supply chain. Spiker said that gave her confidence it would shed light on vegetable deliveries as well.

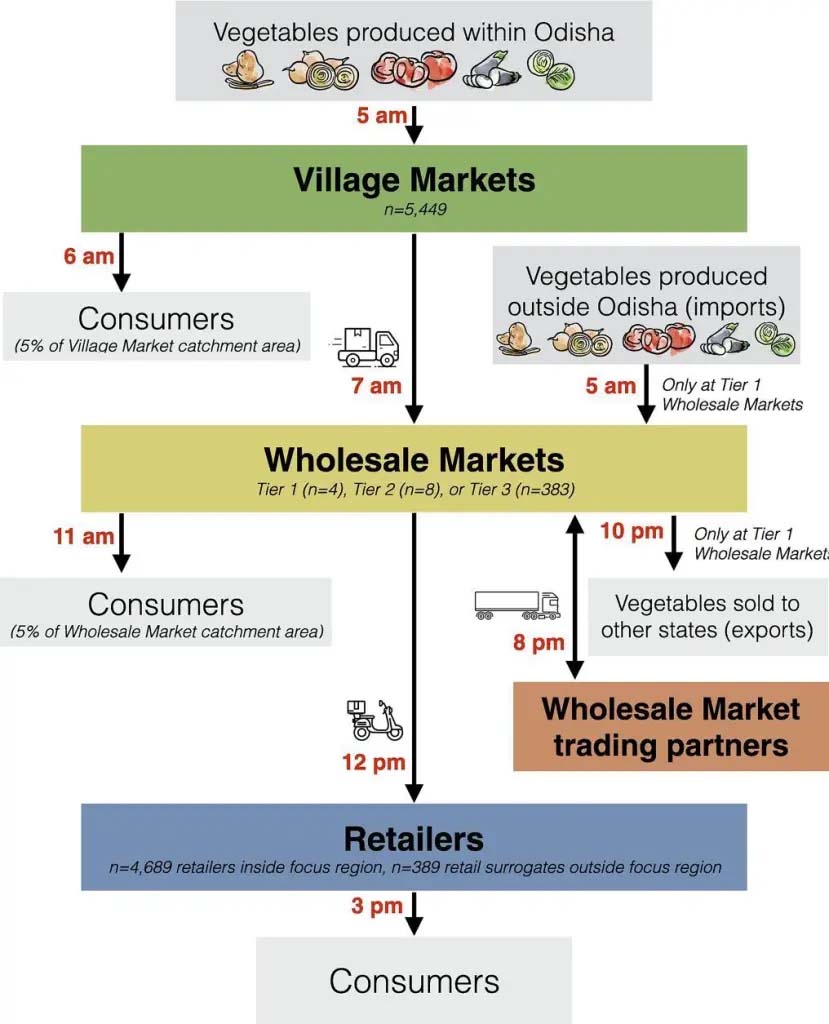

Supply Chain Structure. Vegetables entered the supply chain at village markets or wholesale markets, and they exited the supply chain when consumers purchased them at village markets, wholesale markets, or retailers - or when they were lost to breakage or spoilage en route. From Spiker ML et al. When increasing vegetable production may worsen food availability gaps: A simulation model in India. Food Policy 116(2023):102416-102430.

In the HERMES simulations, increasing vegetable production up to five times what's currently grown changed the retail availability of the veggies by between an increase of 3% and a decrease of 4%.

"[When] people aren't eating as many vegetables as we want them to, it seems like we should produce more vegetables," she said. "But if we increase vegetable production without paying attention to supply chains, we risk this situation where the money we spend on crop productivity may literally go to waste if the food ultimately does not reach people."

For example, doubling production of eggplant, known locally as brinjal, led to only a 3% increase in deliveries, partly because spoilage en route increased by 19%. The system didn't have the refrigeration or other means needed at intermediate storage areas to keep the food fresh. The team reported their results in the journal Food Policy in 2023.

This initial study showed that HERMES works just as well on food supply chains as it did on medical supplies. Though no simulation model can capture every single possible detail within a complex system, this adaptation of HERMES captured the core dynamics of food distribution systems in this setting. This success offers lessons for how we think about meeting the growing need for perishable, nutritious foods. The results show that increases in food production need to be accompanied by a detailed understanding of food supply chains in each country, if we want crops to feed people rather than going to waste. There's also potential for additional analyses, to explore further supply chain dynamics and make more specific recommendations. The collaborators plan additional studies on the food security impacts of decreased crop production (for example, in response to crop failures or climate impacts) and cold storage systems.