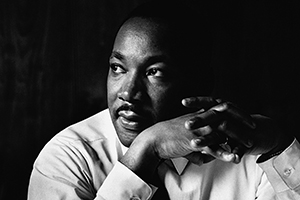

MLK Jr. Writing Awards

Students Share Personal Reflections in Prose and Poetry

by Shilo Rea

From violence to discrimination,

teenagers and young adults are not immune to the ugly side of humanity. For some, writing provides a creative outlet that can help them explore their feelings and put them on a path toward healing.

From violence to discrimination,

teenagers and young adults are not immune to the ugly side of humanity. For some, writing provides a creative outlet that can help them explore their feelings and put them on a path toward healing.

For the 16th year, Carnegie Mellon invited Pittsburgh-area high school and college students to submit poetry and prose pieces about their personal experiences with race, discrimination and other obstacles as part of the university’s annual Martin Luther King, Jr. Writing Awards.

Here are three winning pieces.

First Place, High School Poetry

Alexis Payne

Pittsburgh CAPA

Strange Fruit

You wonder what ‘strange fruit’ tastes like

as you swing ashy legs from the hips of your father’s

reclining chair. when you ask his face

contorts into a shadow, cheeks pressing air

from the edges of his jawbones,

eyes hollowing.

you are watching his hands curve

into fists — red blisters, stitches,

hard knuckles pressing into working skin…

and in the place beneath your tongue,

you are imagining the soft flesh of a mango

pulp of an orange

tart bursting body of a strawberry.

when you ask him again, he is silent

and pressing his fingers against the temples

of his head, imagining asphyxiation

suffocation…toes dangling and shadows

in woods.

you are not his daughter here.

here you are Emmet’s sister,

Evers’ daughter, little brown

church girl lifting her skirt

to use the bathroom…

the face of Jesus,

a hollow, jagged shadow.

he is swallowing and searching

for what strange fruit tastes

like in the back of his throat,

like maybe he can recall from his taste buds,

pull it out from the silence

between his lips,

like strange fruit has been caught

between his teeth

or is hiding, resting on his gums.

wherever it is, you decide

that he hasn’t swallowed it yet

and you imagine it sputtering onto the carpet

in a burst of ebony vomit.

years later, when it dries and you’ve grown…

you scrape it up with your nails and you watch

as the black turns to

red,

then white,

then blue.

Third Place, College Poetry

Joshua Brown

Freshman in the Dietrich College

When I was Born, I Came out Swinging

When I was born, I came out swinging.

I spanked the nurse, and he tried wringing

My little neck.

I spanked the doctor, and she cried while bringing

My bassinet.

When I was born, I came out singing.

I tried harmonizing, desperately clinging

To the hope that I would emerge to find

A world willing to embrace the differing

Pitch of my discordant heart strings.

When I was born, I came out swinging,

Prepared to beat back the savage stinging

Of this world’s brutal preoccupation

With my private passions.

When I was born, I came out singing

The praises of doves, gracefully winging

Across my future's love-torn horizon,

Rebuking Cardinals for their bloody

Prejudice.

My heart never stops tingling

With love for lovely men and women,

This part of me, ceaselessly ringing

With rage for mankind's withheld

Kindness.

When I was born, I came out.

Wasn’t once enough?

Third Place, College Prose

Michelle Mathew

Junior psychology and creative writing major

Excerpt from “Fair and Lovely”

I’m eleven years old. My aunt is brushing my hair. She’s going to brush it all the way back and tie it up in a ponytail. The brush pulls hard at my hair and I know it’s probably going to hurt when she ties it up tight at the end. I don’t like the way my forehead looks when she brushes the hair back. Now I can clearly see my eyebrows — bushy, like my mom’s, who at least gets to pluck hers into nice, clean arches. I always hated having my hair tied up in a ponytail.

When my aunt finishes brushing my hair I want to run away — I’ve been standing here for half an hour. I want to go downstairs and play with my cousins before we have to go to church. I’ll bet the ceremony will be like the one at my last uncle’s wedding. They’re always long, but I never know exactly how long because the priest speaks like he’s shouting, into a microphone, in Malayalam, and I don’t speak much Malayalam, so I can never tell what part of the ceremony we’re at.

But I’m not allowed to leave yet. She takes out a plastic container of powder, the same kind she’s been putting on her face. The powder is sort pinkish. I didn’t know I had to wear it too.

“Close your eyes.” She tells me. I close my eyes and pinch my mouth shut while she rubs the powder all over my face. She rubs it so hard that for a second I’m scared I can’t breathe. When I open my eyes she turns me around to the mirror and smiles.

“There. Now your skin looks nice and fair.”

Fair. She doesn’t mean it the way teachers say it at school, when they talk about treating other people like you would want to be treated. When she says “fair,” she means “not tanned.”

Downstairs, the rest of my cousins are waiting to leave. Mithun, who is three years younger than me, takes one look at me and starts laughing like I’m the funniest thing he’s seen all day.

“Meesha penna!” he yells. Mustache girl.

I run all the way back to my grandmother’s room with my hand covering my mouth, crying. I beg my aunt to let me take the powder off. It’s making the fine hair on my upper lip show through. I don’t want to go to church looking like this.

“You look beautiful.” She tells me.

“No I don’t.” I sob, “I have a mustache.”

I can’t remember if we argue over this in English or Malayalam. I would like to think it was in Malayalam, because her English is sort of choppy — not broken, but not fluent either. Maybe I spoke in English and she responded in Malayalam. That’s the way a lot of dialogue between me and my relatives goes. I go to church with my face still pinkish. I look fair. My other aunts tell me I look lovely. They think I look better, in a country where so many people are naturally tanned and wishing they weren’t. I’m eleven years old and I don’t understand.