Judy Resnik: Family, Friends Remember Engineer Who Reached for the Stars

By Chriss Swaney

Their tears and silent moments said so much.

Family, colleagues and friends of Judith A. Resnik don’t want her just to be remembered as one of the seven astronauts who died in the Challenger Space Shuttle breakup 25 years ago.

Family, colleagues and friends of Judith A. Resnik don’t want her just to be remembered as one of the seven astronauts who died in the Challenger Space Shuttle breakup 25 years ago.

“We would like her to be remembered for her legacy as the second American woman in space, a diligent student and a wonderful human being,” said Helene R. Norin, of West Akron, Ohio, Resnik’s cousin. “She was bright and interested in the sciences. In fact, the large extended Resnik family has always placed great emphasis on academic achievement.”

Resnik, who graduated valedictorian in 1966 from Firestone High School in Akron, was described by old friends there as a student who excelled in mathematics and classical piano.

“She was a math whiz, but at some point math lost the numbers and she wanted something more tangible so she switched her collegiate major to electrical engineering,” said Michael D. Oldak, another electrical engineering major at Carnegie Mellon, who became her boyfriend and husband. Oldak is vice president and general counsel of Washington, D.C.-based Utilities Telecom Council, a global trade association dedicated to creating a favorable business, regulatory and technological environment for companies that own and manage critical telecommunications systems in support of core business. “She had a great sense of humor and was always willing to try anything. I remember taking her to Kennywood to ride the rollercoasters. At first, she hesitated. But once she took a ride, she was hooked and rode them all.”

Resnik received a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from Carnegie Mellon in 1970 and a doctorate in electrical engineering from the University of Maryland in 1977. She worked for RCA beginning in 1971 as a design engineer, which included engineering support for NASA telemetry system programs.

Resnik received a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from Carnegie Mellon in 1970 and a doctorate in electrical engineering from the University of Maryland in 1977. She worked for RCA beginning in 1971 as a design engineer, which included engineering support for NASA telemetry system programs.

From 1974 to 1977, Resnik was a biomedical engineer and staff fellow in the Laboratory of Neurophysiology at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md. She worked for about a year as a senior systems engineer in product development with Xerox before being selected by NASA in 1978.

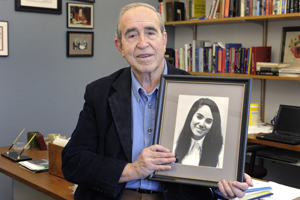

“When she heard NASA was looking to incorporate female astronauts, she asked me what I thought about it, and I encouraged her to apply,” said Angel Jordan, a university professor emeritus, provost emeritus and Resnik’s faculty adviser and mentor. “She was an amazing person.”

With a long pause and a quick blink to hold back tears, Jordan says he still feels a bit responsible for her loss. “I pushed her to excel, and I live with that memory every day,” he said.

Across campus, Jerome “Jay” Apt III recalls that he spoke with Resnik a few days before the shuttle loss.

“She was an excellent pilot and a superb operator in space,” said Apt, a veteran astronaut who flew four missions aboard the Atlantis and Endeavour shuttles in the 1990s. He also is a professor of technology at the Tepper School of Business and in the Department of Engineering and Public Policy, and executive director of the Carnegie Mellon Electricity Industry Center.

“She was the kind of astronaut that we could all emulate. I’m certain that she would have flown more times if the Challenger had not been lost,” Apt said. “The accident was significant because it ultimately prompted a whole set of changes at NASA.”

Resnik, who was a mission specialist on that flight, had logged more than 145 hours in space. Because many of the family members were involved with Resnik’s first shuttle trip aboard Discovery, when it came time for her to be on the Challenger, it wasn’t on the top of everyone’s mind, according to Norin, an audiologist. Her brother called her from California to tell her about the explosion that followed the launch.

Resnik, who was a mission specialist on that flight, had logged more than 145 hours in space. Because many of the family members were involved with Resnik’s first shuttle trip aboard Discovery, when it came time for her to be on the Challenger, it wasn’t on the top of everyone’s mind, according to Norin, an audiologist. Her brother called her from California to tell her about the explosion that followed the launch.

He said, “Helene, you better sit down,” she recalled. At that instant, her husband and receptionist from her Akron office came in to bring her home because they knew she would not be able to drive herself.

“It was shocking,” she said. “They were all so confident, we never thought anything could go wrong.”

As the nation mourned the loss of Resnik and 16 other fallen astronauts Jan. 28, 2011, at Arlington National Cemetery, solemn, singular remembrances continue to unfold for Carnegie Mellon’s famous alum.

And members of Tau Beta Pi will spend an afternoon polishing the Judith A. Resnik memorial at the base of

Hamerschlag Hall.

“She loved Carnegie Mellon, and perhaps her pioneering spirit lives on with my 13-year-old grandson Tyler, who wants to be an astronaut and

perhaps attend Carnegie Mellon,” Norin said.

Judy Resnik

Angel Jordan, a university professor emeritus and provost emeritus, was Resnik’s faculty adviser and mentor. “She was an amazing person,” Jordan said.

A memorial to Judith A. Resnik resides at the base of Hamerschlag Hall. Members of Tau Beta Pi, the National Engineering Honor Society, help maintain the monument.