October 27, 2017

Neurons to Neighborhoods Focuses on the Teen Brain

When it comes to our brains, our teenage years form a critical intersection between opportunity and risk.

While adolescence is often thought of as a time of turmoil and poor decision-making, it is also an exceptional time of discovery. Adolescence sensation seeking is driven by heightened reactivity to rewards and emotion and can lead to risk-taking, including peaks in car accidents, and experimentation with drugs, unprotected sex and crime. However, this is a necessary time of enhanced learning and exploration that are critical to the transition into adult independence.

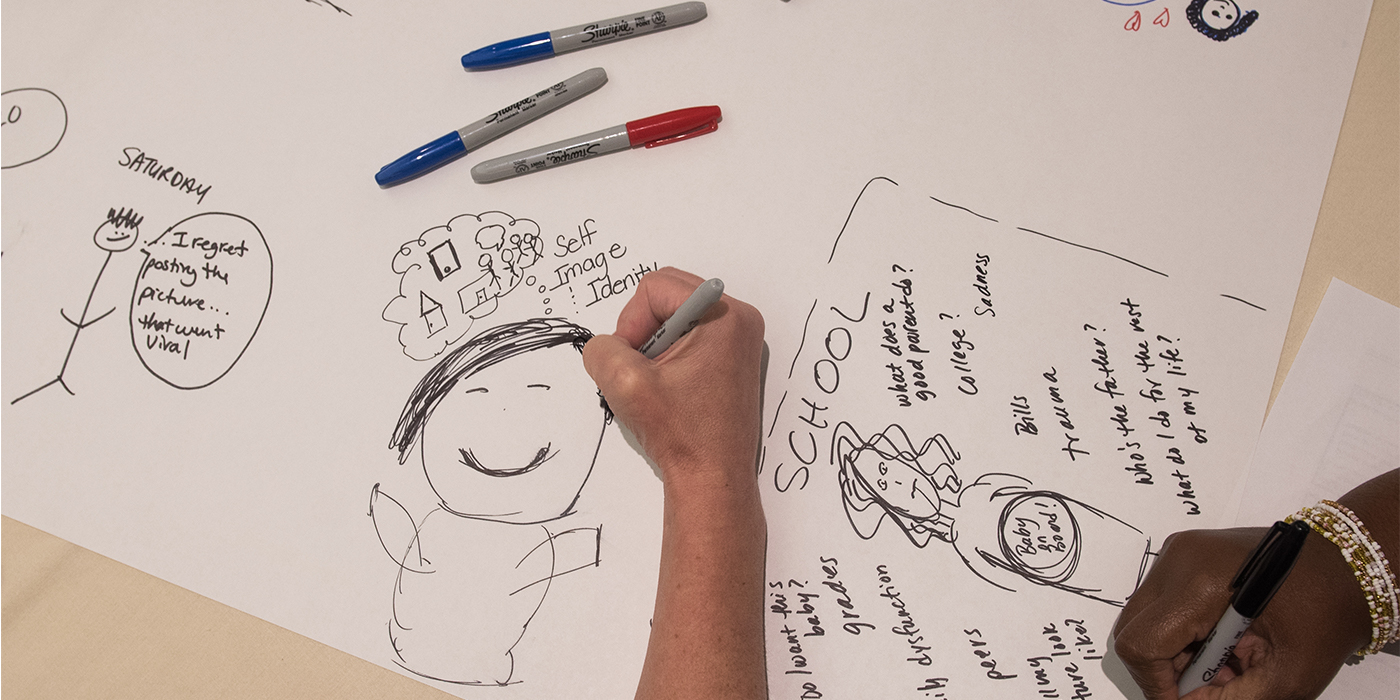

Those were some of the main messages to come out of day-long seminar in early October at Carnegie Mellon University on the teenage brain, sponsored by the Heinz Endowments and by CMU’s BrainHub, a research institute combining the university’s expertise in neuroscience, biology, psychology, computer science, statistics and engineering.

It was the second in BrainHub’s “Neurons to Neighborhoods” series, designed to introduce the latest brain research to teachers, social workers and nonprofit and foundation leaders who work with children and others in the community.

“Educators and those who interact with teens have the potential for unparalleled impact on our youth and our communities,” said Michelle Figlar, vice president for learning at the Heinz Endowments. “They know firsthand the complexity with which teens interact with the world, and having research like that of the BrainHub community—done right here in our city—is an extraordinary resource for the work they do.”

Keynote speaker Beatriz Luna, the Staunton Professor of Psychology at the University of Pittsburgh, summed up the teen years this way:

“As you know, with teenagers, sometimes [our reaction to them is] ‘That was incredible, you responded just like an adult!’ and other times, it’s like, ‘What were you thinking?’”

Luna is a pioneer in doing brain-imaging experiments with teenagers to understand how brain function and brain connections change with cognitive development. One finding that may surprise people is that teenagers’ brains are very much like adults’ but they are in an active period of evolving into adulthood. So while at times they can reason just like adults this happens less frequently. Their brain is actively sculpting in response to their experiences as synaptic connections prune in a “use it or lose it” manner and major connections to affective regions decrease while those related to integrating experience increase informing reasoning brain regions.

In adolescence, the emotional centers of the brain have greater influence in their behaviors but as they grow into adults these diminish allowing reasoning areas to lead the way.

Experts now believe that shift toward the adult brain takes longer than was once believed. In fact, some feel that adolescence today lasts until about age 25.

Julie Downs, associate professor of psychology, social and decision sciences at Carnegie Mellon andone of the conference speakers, said research has shown that teens can make decisions that are just as mature as those of adults when they are in a “cold” state— a time when they can think calmly and rationally.

But when they are in a “hot state,” she said—those times when emotions are running high—they can act more impulsively than adults.

One of her main goals is to give teens the ability to plan for critical actions—like when and how to have sexual relationships—when they are in “cold” moments, and then give them scripts they can use for what to say and do when those “hot” moments arrive, as when a boy at a party wants a girl to have intercourse.

To combat sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancies, her team has developed an interactive video, Seventeen Days, to help teen girls learn how to make sound decisions during emotionally charged moments. This is a key example of CMU’s approach to behavioral economics that tackles complicated problems using a distinct fusion of economics and psychology.

Another technique highlighted at the BrainHub conference was mindfulness meditation – a technique for getting people to control their breathing and focus completely on the moment.

Brian Galla, a professor in Pitt's Psychology in Education program, said that programs like Inward Bound, which run summer camps in mindfulness training, have shown that teens who go through the program have better self-control, less depression and rumination and even better working memory function.

“There is an enormous amount of strength we can capitalize on if we look at teenage years as a time to thrive,” Galla said.

Gerry Balbier, executive director of BrainHub, was encouraged by the exchange between attendees.

“As a research institution, we continue to gain valuable insights as we actively discuss discoveries about the human brain with our neighbors across the region who have committed their careers to providing services to improve the lives of children and youth,” Balbier said. “This community engagement work remains a priority for CMU and the BrainHub initiative.”

_____

Media Contacts: Jocelyn Duffy or Shilo Rea