Out-of-date Data May Contribute to Future Flooding in the U.S.

By Adam Dove

Media Inquiries- College of Engineering

A recent study by Carnegie Mellon University researchers indicates that out-of-date precipitation data used by state department of transportation offices may be increasing the risk of flooding by not providing sufficient information to design and build adequate stormwater infrastructure.

Published in Environmental Research Letters, work by Civil and Environmental Engineering Ph.D. student Tania Lopez-Cantu and Associate Professor Costa Samaras reviewed the state DOT design manuals of the 48 contiguous states and the District of Columbia. DOTs use these manuals to guide infrastructure planning and construction including sewer lines and curbside grates. But according to this research, some of these manuals are based on out-of-date precipitation data, and none directly account for future climate change, which could spell trouble for many state residents.

"As greenhouse gases from human activities have increased in the last few decades," Samaras said "our air has gotten warmer, and warmer air can hold more water. Many cities and communities are experiencing heavier rainfall, and storm water infrastructure can't seem to keep up — which can lead to dangerous flash flooding and infrastructure failure."

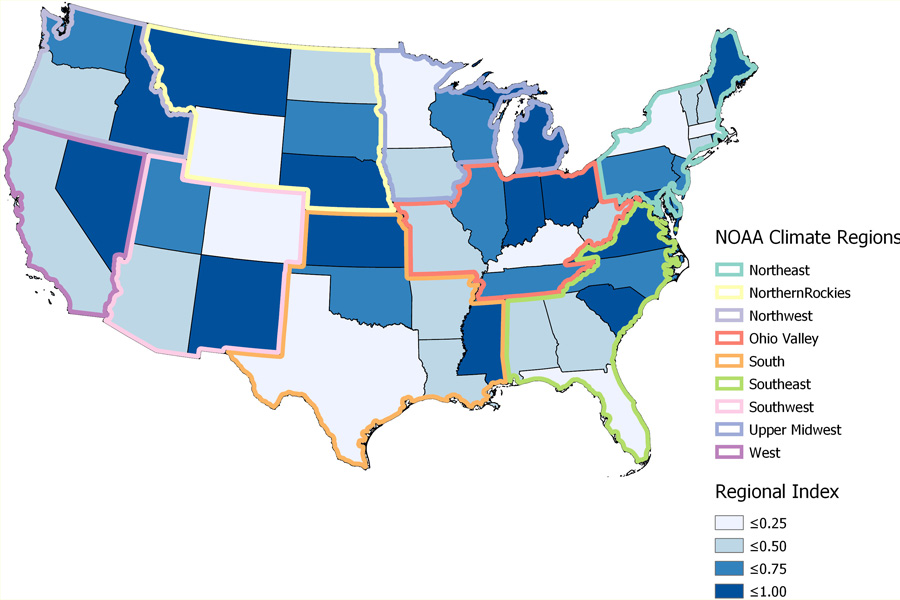

A map shows comparisons between state Department of Transportation stormwater standards within a NOAA climate region. Higher values represents states that have higher standards (and thus, are more prepared for rare storm events) compared to the other states within the same climate region. Lowest values describes states that have the lowest guidelines in the region.

As part of their research, the team examined precipitation levels provided in federal government documents used for infrastructure design for each state spanning from 1961 to the most recent updates starting in 2004. In this period, 43 states showed statistically significant precipitation changes in more than 90 percent of the study area. This means that any infrastructure installed before the most recent update to these manuals might not be equipped to handle present and future climate conditions. Using this analysis, the team sorted states into four categories to prioritize which states should update their stormwater design manuals first. The highest priority states were chosen based on three criteria:

- They experienced a 10 percent or greater increase in precipitation between 1961 and 2000;

- They published their most recent design manuals prior to the release of the last precipitation document; and

- They were in the lower half of their regional index, which compares if states in the same climate region are designing the same stormwater infrastructure for a 25-year storm versus a 50-year storm, for example.

"Under higher return periods," Lopez-Cantu said, "many states in the northeast and upper midwest were found to be in high priority categories. These states should update their design standards to ensure new drainage infrastructure performs under current and projected precipitation levels."

The team found that stormwater infrastructure risks would go up in all states under climate change. If these design manuals are not updated with the most recent precipitation data, as well as planning for a future climate for all stormwater infrastructure, it is likely these high-priority areas - and eventually all other areas as well — will face severe street flooding.