Engineers Take Steps To Prevent Falls

Sensors on hospital beds can predict a patient's movements

One of four elderly persons falls every year in the United States. With more than 37 million hospitalizations annually, roughly one million falls occur in hospitals and can lead to serious injury and even death. Hae Young Noh, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Carnegie Mellon University, is developing sensors that predict when a person is about to fall by sensing the vibrations from a person's movement. Using signal processing and machine learning, her sensors detect the movement of a person and characterize what those movements mean.

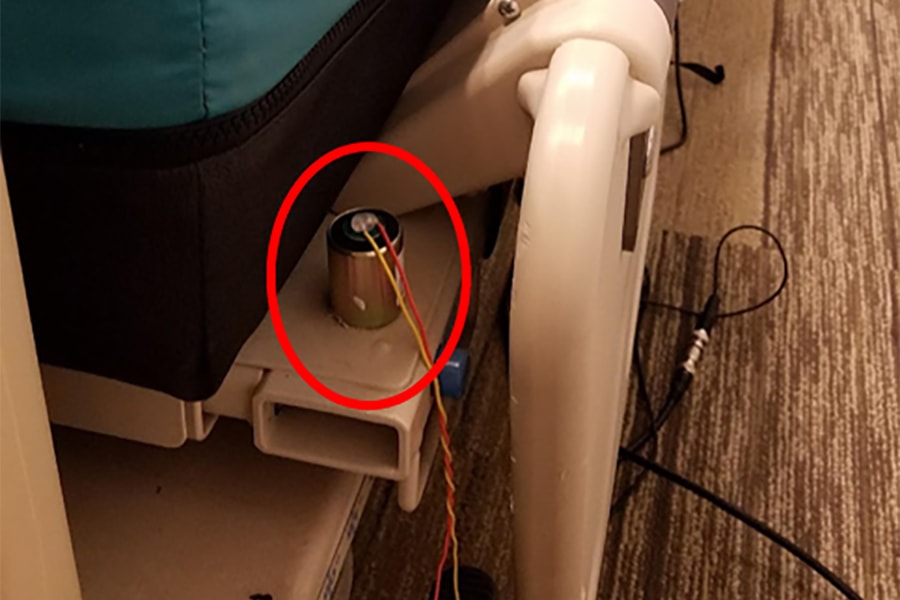

Unlike other sensors that monitor patient movement or vital signs, Noh's sensors identify the intent of a person's movements — whether they are preparing to exit the bed or just rolling over and sitting up. These sensors, placed on the bed frame, will alert the nurse when it predicts a patient may be getting up, so the nurse can get to the patient in time.

Just like a pebble creates waves when dropped into water, people's movements and contact with objects also create waves that a sensor can detect. The sensors contain accelerometers that detect wave signals that propagate through the bedframe. They utilize signal processing methods and machine learning techniques to classify the vibration, determining whether the patient has an intent to get out of bed or not.

A sensor attached to a hospital bed. Assistant Professor Hae Young Noh is developing sensors to predict when a person is about to fall.

Highly accurate and highly sensitive, the sensors can also be placed on the floor to detect when a person's gait, or manner of walking, is deteriorating. The sensors can locate each footstep with less than 0.34 meter of error, about the size of a foot, which allows them to detect walking speed, stride length, and step frequency-factors related to predicting fall risk. The system can also estimate individual footstep forces and left-right balance of footstep forces within 5 percent error of body weight.

"Some people can only walk about 10 steps," Noh said. "And they used to be healthy, so they are going to try to take the 11th step. Because it's over their limit, the risk for a fall increases, and it shows in the gait deterioration pattern before it actually happens. We're trying to detect that pattern."

Noh's team will soon deploy the sensors in hospitals for testing. Doctoral students Mostafa Mirshekari, Jonathon Fagert and Shijia Pan, and Electrical and Computer Engineering Associate Professor Pei Zhang are collaborators on the hospital bed sensors project.

"Patients may be too shy and don't want to worry others," Noh said. "But information about their symptoms is sometimes critical. So, if a sensor can pick them up and notify the caregivers, families, or doctors, it could help with prevention and treatment."