|

|

||

|

|

|

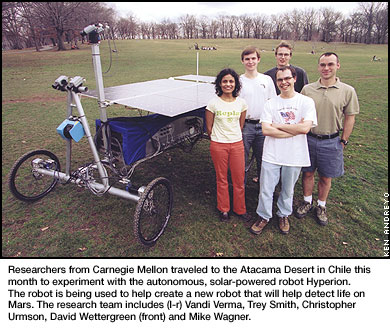

Carnegie Mellon, NASA Researchers to Develop Life-Seeking Robot for Distant Planets � A team of scientists from Carnegie Mellon and NASA traveled to the Atacama Desert in northern Chile this month to conduct research that will help them develop and deploy a robot and instruments that may someday enable other robots to find life on Mars. The researchers are using the Atacama, described as the most arid region on Earth, as a Martian analog. The group is funded with a $3 million, three-year grant from NASA to the university's Robotics Institute. They are collaborating with scientists at Carnegie Mellon's Molecular Biosensor and Imaging Center who have a separate $900,000 grant from NASA to develop fluorescent dyes and automated microscopes that the robot will eventually use to locate various forms of life. The project falls under NASA's Astrobiology Science and Technology for Exploring Planets (ASTEP) program, which concentrates on pushing the limits of technology in harsh environments. NASA experts believe that by pushing the known limits of life on Earth, scientists will be better prepared to search for life on other worlds.

This year, the team will be using an autonomous, solar-powered robot named Hyperion to determine the optimum design, software and instrumentation for a new robot that will be used in more extensive experiments over the next two years. In 2001, Hyperion was taken to Devon Island in the Canadian Arctic where it successfully demonstrated a concept called Sun-Synchronous Navigation. It tracked the sun as a source of power and explored its surroundings as it traveled continuously through a 24-hour period of daylight. During this year's visit to the Atacama, researchers are focusing on measurements and experiments with the robot's hardware and software components. They will test Hyperion as it travels through the desert and collect data with scientific instruments, including a fluorescence imager, near-infra-red spectrometer and a high-resolution panoramic imager. Wettergreen said that Hyperion would travel some 10 kilometers through the desert this year while the researchers study issues related to robotic autonomy. The robot's solar panels have been laid flat on top of its body for the upcoming experiments so it can capture the maximum amount of sunlight in the equatorial environment. In the Arctic, the panels were mounted vertically, like sails on a boat, because the sun was often low on the horizon. A next-generation robot, developed from the findings of this year's work, should perform 50 kilometers of autonomous traverse in the desert in 2004. In 2005, the final year of the project, a robot equipped with a full array of instruments should operate autonomously as it travels 200 kilometers over a two-month period. During this climactic journey, the robot should map sites where life is abundant, and then move into drier areas where life has not been detected.

In addition to Wettergreen, the Carnegie Mellon team at the Atacama includes William L. "Red" Whittaker, the Robotics Institute's Fredkin Research Professor and the project's principal investigator; Alan S. Waggoner, professor of biological sciences and director of the Molecular Biosensor and Imaging Center; James P. Teza, research engineer; Michael D. Wagner, research programmer; and Robotics Institute doctoral students Christopher Urmson, Paul Tompkins, Denis Strelow and Vandi Verma. Also under development is the capability for education and science communities to experience the mission through the EventScope interface. EventScope converts data from rovers and orbiters into three-dimensional "virtual worlds" that realistically represent remote sites, enabling students to experience the mission from their classroom computers. EventScope's team is directed by Peter Coppin, a research scientist at Carnegie Mellon's STUDIO for Creative Inquiry, and includes experts in software engineering, interactive art and educational technology working to develop next generation tools for public remote experience. The goal is to have hundreds of students participating remotely in the Atacama experiment by the end of 2005. � �

�

Top�

�

�

Anne Watzman

|

|

This Issue's Headlines || Carnegie Mellon News Home || Carnegie Mellon Home |

||

"Our goal is to make genuine discoveries about the limits of life on Earth and to generate knowledge that can be applied to future NASA missions to Mars," said project leader David Wettergreen, a research scientist at the Robotics Institute. "We will conduct three annual field experiments in the Atacama. Each time, an increasingly capable robot will use sensing and intelligence to find land forms or environmental conditions that could harbor life."

"Our goal is to make genuine discoveries about the limits of life on Earth and to generate knowledge that can be applied to future NASA missions to Mars," said project leader David Wettergreen, a research scientist at the Robotics Institute. "We will conduct three annual field experiments in the Atacama. Each time, an increasingly capable robot will use sensing and intelligence to find land forms or environmental conditions that could harbor life."