For millennia, people have told stories of a divine being who floods Earth with punishing waters but spares the lives of humans and animals. Noah and his ark appear in three world religions, and similar ancient stories of collection and preservation have been recorded across the globe from India to Greece to Nigeria.

Now there’s an ark with plans to go beyond the globe.

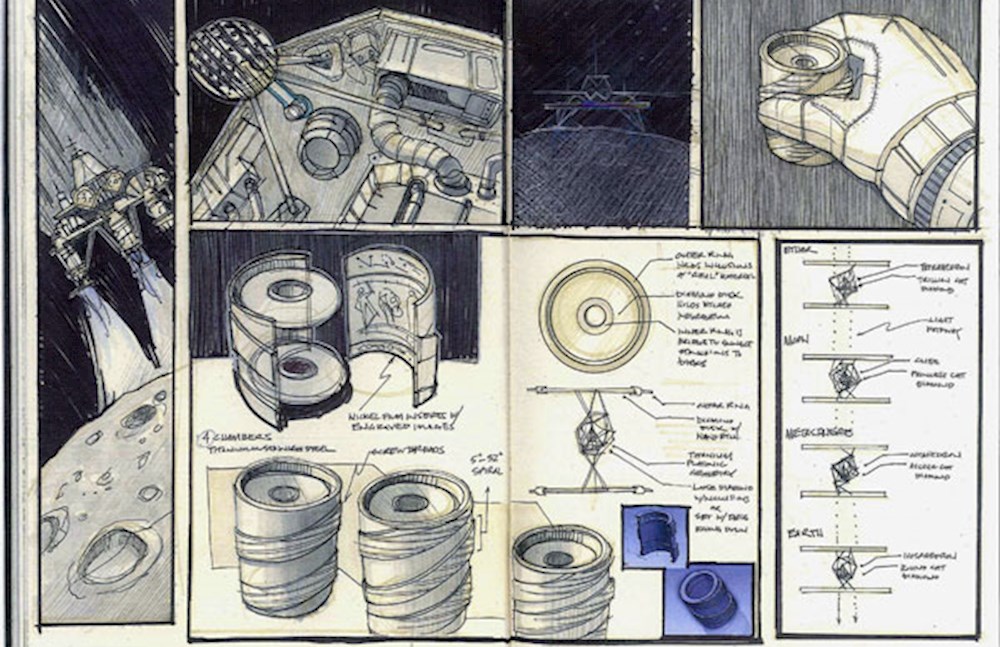

Amid shelves littered with gadgets and walls papered with photographs and drawings, three artists from Carnegie Mellon University’s School of Design gingerly place a few tiny objects on a conference room table.

Mark Baskinger opens a plastic box that contains an engraved sapphire disk the size of a silver dollar. It’s almost like a scene from a James Bond movie, in which Q unveils the latest gadgets for Bond’s next mission. Baskinger, who teaches industrial design on the Pittsburgh campus, holds technologies that have come into existence only recently.

Next to the disk, Dylan Vitone, a photography professor, spreads out a piece of paper and points to four complicated pictures. He begins to describe the elements on the page, and again, it’s almost as if he’s laying out the Byzantine plans by which Bond will thwart a criminal mastermind.

Matthew Zywica teaches drawing and visualization at CMU. He leans back in his chair and gestures to the sketches behind him. “This all changes by day,” he says.

Vitone nods. “The best and worst part of this project,” he adds, “is that it’s so hard to explain.”

Despite the arcane models and innovative technology, these men are talking about something ancient and completely familiar: the moon. They’re talking about artwork they’re sending to space through the Moon Arts Project and how they’ve fit the creativity of Earth into a capsule that weighs only 6 ounces. They’re trying to articulate what it’s like to do something so enormous and so small, something so new and so old.

To understand the Moon Arts Project, you have to go back to the launch of the Lunar XPRIZE in 2007. The XPRIZE foundation aims to facilitate breakthroughs for the benefit of humanity by funding competitions in many fields. Specifically, the Lunar XPRIZE, funded by Google, challenged entrants to achieve a new feat: land a privately funded spacecraft on the moon. The $30 million race aims to pave the way for a new space economy, one that will eventually provide low-cost access to the moon—a kind of UPS truck to space—so that humans might utilize the moon’s natural resources and further investigate its mysteries. With visions of space exploration, industry, and tourism in mind, sixteen teams of elite scientists have competed for the past eight years. Entrants from North and South America, Europe, India, Japan, and Israel are working to create a robot that can land on the moon and send back high-definition imagery, video, and data from the landing site and surrounding area.

It’s no surprise that one competitor, Astrobotic, is headquartered in Pittsburgh, working in conjunction with researchers and students at Carnegie Mellon, home of one of the world’s top robotics programs. If all goes according to plan, in 2016, a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket will launch Astrobotic’s Griffin lander, which will then coast onto the moon and touch down on the Lacus Mortis region. From there, CMU’s Andy Rover, named for the university’s founders, Andrew Carnegie and Andrew Mellon, which was built for the Google Lunar X-Prize Challenge, will strike out onto the lunar surface. The mission will take less than two weeks.

XPRIZE has awarded milestone prize money throughout the race, as teams have demonstrated various hardware and software that will address hurdles in imaging, mobility, and landing systems. The Astrobotic/CMU team is in the lead, having won three such prizes. Its rover will explore lunar pits, the supposed entrances to caves that might contain water or fuel or shelter for further moon exploration. The mission is, obviously, highly scientific. But scientists are not the only ones interested in the moon.

“The ark, like Noah’s Ark, is taking images of life, or actual pieces of life, to the moon,”

What if the project were also artistic? This was the question posed by David Gump, former president of Astrobotic, and by Red Whittaker, CMU professor of robotics and chairman/CSO of Astrobotic. After all, Carnegie Mellon has not only a top-notch Robotics Institute, but also a highly regarded College of Fine Arts. Integrating an arts component would differentiate this team from all the others and create an even more robust entry.

Tapped as the project’s director is Professor Lowry Burgess, who has been making space art since the 1960s. “The artist’s part,” he says, “is to reach out far beyond the knowable to see what’s there long before science can get there to confirm.” Through the ark, he hopes, the two branches of inquiry will reach out together.

In 2007, Burgess put out a call to see who might be interested in collaborating. Mark Baskinger, whose design work has been exhibited in numerous galleries, including the Museum of Modern Art, joined as co-director. Dylan Vitone and Matthew Zywica also came on board in the early stages. The Moon Arts Project eventually coalesced with approximately 40 members, coordinated through the Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry in the College of Fine Arts and funded by multiple universities, corporations, foundations, and individual donors. Today, more than 150 artists, including faculty collaborators from James Madison University and the University of South Carolina, are at work on the project. They’ve also solicited input from the public, giving the project a broader reach.

The ark represents art, architecture, design, music, drama, ballet, and poetry. “The ark, like Noah’s Ark, is taking images of life, or actual pieces of life, to the moon,” says Burgess. Andy Warhol reportedly sent a sketch to the moon on the Apollo mission. In 1977, Carl Sagan created the Golden Record, a disc etched with information about the Earth and launched aboard the Voyager spacecraft. But these are mere shadows compared to the enormity and complexity of the Moon Ark. Nothing like this has ever been attempted before.

So if you’re going to send a tiny museum to the moon, what do you send?

The Ark

In the Quran, Allah gives explicit instructions to Noah to build an ark with broad planks and line it with palm fibers. And in the book of Genesis: “The ark is to be three hundred cubits long, fifty cubits wide and thirty cubits high.” Noah’s Ark was built to withstand a worldwide flood; the Moon Ark was built to withstand a trip into outer space, meaning that the capsule had to provide incredibly durable but lightweight housing for contents that are light, small, and fragile.

The ark is actually four chambers, aluminum exoskeletons each about two inches in diameter and two inches tall; stacked together, they form a cylinder. Fabricator after fabricator originally refused the designers, saying the project was too complex to build with current 3D printing technology. Finally, the team found 3rd Dimension Industrial 3D Printing in Indiana. After one machine meltdown and many months, the company successfully built the chambers.

These aluminum structures—pieces of art themselves—are lightweight but also symbolic: they, as well as some of the pieces within, are icosahedrons. (Picture the 20-sided die from Dungeons & Dragons.) This shape most nearly approximates that of plankton, the most basic life form and one of the central players in the ark’s narrative. The chambers are named Earth, Metasphere, Moon, and Ether, representing an outward progression from our physical world into deep space.

But the project was not as simple as building an ark and filling it with animals. While the team was designing the exoskeleton, it was simultaneously imagining the contents. Burgess likens the process to “playing on many chessboards at the same time.” Each chamber contains four micro-etched sapphire disks, impossibly small sculptures, microcapsules containing evidence of life on earth, images on metal foil, and more. But the team knew from the start it couldn’t represent everything; the project is meant to be illuminating rather than encyclopedic.

“Late at night, alone somewhere, just looked up at the moon and really felt something—something that pierces us in an emotional way?”

So what is in the ark when you finally look inside?

Earth

Interdisciplinary artist Carolina Jacobs Ramos peers through a microscope, observing some of the plankton she and her colleagues have collected worldwide. These “swimming guys,” as Ramos calls them, are the building blocks of life. From algae to jellyfish, plankton create oxygen and filter water, shaping our atmosphere and our world. They wander throughout the planet, completely at the mercy of the tides, which, as we know, are generated by the moon.

So in a literal sense, these plankton are earth’s building blocks. But the plankton are also a helpful metaphor for the nature of the Moon Arts Project. Plankton are guided by the moon, unmoored from any place, and representative of the symbiosis at the core of our planet’s evolution.

An artist and therapist working at a mental health clinic in New York, Jacobs Ramos has been part of the project from its embryonic stages. As a CMU student, Ramos studied with Burgess; she now collaborates with him and artist Robb Godshaw on a sculpture for the Earth chamber. Their piece, “The Wanderers,” is a minuscule cage-like structure that holds dried zooplankton and phytoplankton.

In some ways, the Earth chamber feels as all-encompassing as Noah’s ark. “From birds of every kind, cattle of every kind, every kind of creeping thing on earth, two of each shall come to you to stay alive,” God directs Noah in the Torah. Likewise, the Earth chamber contains the migration patterns of arctic terns and humpback whales etched onto one disk. Tiny capsules contain minerals and synthetic human blood. Representations of landforms, built objects, living creatures—from there, the project takes off.

Metasphere

Dylan Vitone’s photographs have hung on the walls of the Smithsonian, but now, as he describes the Metasphere chamber, he points to a mural smaller than his palm. “This is a picture of pumpkin bread. I ate the entire loaf.” He’s narrating one of his art pieces, a collection of photographs he and his wife have texted to each other during the entirety of the project—a nod to the way that we broadcast our lives through social media. Originally, the ark images were going to be etched, but recently developed technology allows the Moon artists to print high-resolution dye sublimation imagery on metal foil.

The ark has responded to dynamic technologies from the start. Another piece in the Metasphere includes Tweets turned into graphic images—the chamber swarms with the intangible layers of communication we send into the world, hoping they will be received.“Nothing is guaranteed in life,” says Vitone. “[The ark] becomes this analogy of the blind faith with which we function every day.”

The same blind faith that lets us shoot for the moon.

Moon

Jim Daniels, CMU Thomas Stockham Baker University Professor of English, scrolls through a file of poems by writers including Federico García Lorca, Sylvia Plath, and Margaret Wise Brown. “It’s wacky,” he says, smiling. Daniels was skeptical of the project at first but eager to collaborate with the “intellectual firepower” on the team.

Burgess asked Daniels to contribute poems but wasn’t clear about how many. Like the wandering plankton, perhaps, the artists would be pulled this way and that, and the project would unfold organically. Daniels started by reading hundreds of moon poems. He found a great deal of humility in many of the works, as well as humor, combined with a strong sense of wonder about the moon and what it reveals of our place in the universe.

Although he put in months of research to carefully select poems that span history and the globe, Daniels also knew his choices would be somewhat whimsical. Like the project at large, he couldn’t account for everything. Ultimately, 113 poems will be etched onto discs, fanning out in rays, each poem on one line, in English and another one, two, or three randomly selected languages—a symbolic acknowledgement of Earth’s diverse tongues. At least one poem from Daniels’ book Apology to the Moon will be included.

Poets have been talking to this satellite for ages. One beauty of the Moon Ark is that it’s big enough to encompass many impressions. It’s about everyone and it’s for everyone. “Who hasn’t,” Daniels says, “late at night, alone somewhere, just looked up at the moon and really felt something—something that pierces us in an emotional way?”

Ether

And what lies beyond the moon?

The Ether chamber contains, in part, artwork by Burgess, a pioneer of space art and the driving force behind the ark. It’s the most abstract of the chambers, representing humans’ eventual journey into space. Burgess, whose paintings appear on metal foil, describes it as a “song to the moon.”

It’s fitting that he wants to make this gesture. He’s been engaged with deep space for most of his career and was creator of the first official artwork taken into space by NASA. His life work, “Quiet Axis,” comprises eight major works and 60 preparations on land, in outer space, and in the ocean. Like the plankton, Burgess is unrestrained by nation or border—or even by Earth’s atmosphere. Now, threads of this work weave throughout the Moon Ark as Burgess strives to create this “vast and very complex poem, like Dante’s Divine Comedy.”

But the ark is meant to stick around far longer than any book. Whereas Earth’s oldest intentional art is thousands, if not tens of thousands of years old, the absence of moisture, atmosphere, and erosion on the moon means that the ark might last millions if not billions of years.

This is one of the visions of the project, Baskinger says; encouraging people to “think in longer horizons of time.” Everyone involved has to think long and large as they make sure individual parts collaborate seamlessly in this complex array. “A Carnegie Mellon mashup,” Baskinger calls it.

It’s not just Carnegie Mellon, though. The ark contains voices from around our planet. For instance, the Moon Drawings portion of the ark, led by CMU faculty members Golan Levin and David Newbury, includes sketches solicited from the public.

Baskinger says the team originally thought of the ark as a pristine, vacuum-sealed repository of information, but instead, it’s messier than that—an evolving statement about humanity, covered in myriad fingerprints. He explains, “The fact that it’s imperfect says more about us.” Daniels agrees: “We’re these imperfect beings who can laugh at ourselves and who have a strong sense of wonder about the universe.”

The Olive Branch and the Dove

As the floodwaters recede in the Genesis story, Noah sends out a dove to seek dry land. Eventually, the dove returns with an olive leaf, a sign that the ark’s inhabitants can return to solid ground.

In 1969, the Apollo 11 astronauts left a gold pin in the shape of an olive branch on the moon. Then-President Nixon’s steel plaque remains as well, announcing, “We came in peace for all mankind.” Subsequent missions left other formal markers as well as the wreckage of spacecrafts, leftover food containers, bags of urine and feces, and numerous items both symbolic and insignificant. So what does it mean for humans to leave things on the moon, and what does the Moon Arts Project team think about its stewardship of this lone satellite? Do they really think that someone or something will find—and understand—the ark one day?

The artists have grappled with these questions for years. The Moon Arts Project complies with existing space laws and policies, and Baskinger, Vitone, and Zywica shrug at the inevitability of human traffic in space. But if we’re leaving breadcrumbs, Baskinger says, they “should be carefully considered and not just random happenstance.”

Even if the ark does not make it to the moon, the project will not be lost. A twin will be exhibited around the world, though it’s not yet certain how, because the contents might fill the Louvre.

The artists have varying opinions about how the work might be received. Baskinger doesn’t think most individuals will engage with every part of the project, but he isn’t worried. “This is our artwork, showing our human capacity for creativity. In the future we hope that it … does make a good statement about who we are and why we put it here.”

Zywica adds, “I still look at this thing and wonder: Why does it take that form? How is it meaningful in that respect? We could talk about that for six months.” But, he says, “We’re not trying to give an answer to anything.” They’re just trying to make space for conversation.

If the ark is a song, the creators hope it might be sung with. “Anyone who survives a billion years and arrives on the moon will be pretty intelligent and will be able to figure out the project,” Burgess says.

But who can say? At the end of the Genesis story, Noah sends out the dove a second time, but this time it does not return. The ark will eventually be installed on the four corners of the Griffin lander and set loose on the moon. The point is not for it to come back, but rather to let its complex melody take wing.

So close to completing the task, the team fine-tunes the ark, which will soon undergo space-readiness testing. They’re right: The best and the worst part of the project is that it’s so hard to explain. It’s a poem, it’s a song, it’s a museum, it’s a cathedral. It’s wonderfully labyrinthine. As Burgess puts it, “We’re saying, ‘Hey moon, here we are.’” But the Moon Arts Project is also talking back to the Earth—“to get people to be aware of what and who we are.”

In his view, Burgess adds, “We could certainly use a little bit of that.”