Koedinger Challenges Conventional Education

If your child gets sick, you wouldn’t give her medicine that hadn’t been tested to make sure it works. You wouldn’t take her to a pediatrician who didn’t rely on sound medical research. Yet few of us even blink at sending our children to schools where even the most gifted teachers are unfamiliar with the best research into how children think and learn.

Just ask Elida Laski. A former kindergarten teacher, she was a literacy coach in the Boston public schools when she discovered how little her fellow teachers knew about educational research.

“Education suffers to the extent that teachers are guided often by their own intuition and their own philosophies, so instruction can vary greatly from classroom to classroom and from school to school. Few teachers are guided by established learning theories,” Laski said.

Now, Laski is in a position to do something about it. She’s enrolled in the Program in Interdisciplinary Educational Research (PIER), a Carnegie Mellon initiative to train doctoral students from several disciplines—including psychology, computer science, philosophy and statistics—to conduct applied educational research. PIER is funded through a 5-year, $5 million U.S. Department of Education grant.

PIER is but a single example of Carnegie Mellon’s multi-faceted education research initiatives. Decades of research examining human thought and learning have produced revolutionary advances in education technology and teaching methods. Although the university has no education school, its interdisciplinary culture has propelled researchers in departments ranging from Psychology to Statistics to Computer Science to produce innovations that are revolutionizing K-12 and college classrooms. Among the most exciting examples is Cognitive Tutor, a comprehensive secondary mathematics curriculum and computer-based tutoring program that is in use in 2,000 schools nationwide, thanks to the spin-off company Carnegie Learning, Inc.

All the university’s education programs share a common goal: to raise student achievement through rigorously tested technology and curricula and to help teachers and school administrators make data-driven decisions to improve learning.

The first step is to produce the research, which is where PIER comes in. In addition to fulfilling the requirements of their own departments, PIER students are required to take a three-course sequence to train them to perform education research. They must complete a field project in an educational setting—working either in the classroom or with school administrators—and their dissertations must address an education question. In exchange, the students receive a generous stipend and up to $12,000 toward tuition. Now in its second year, PIER has 11 students.

“The program is premised on the notion that you can’t teach old dogs new tricks, so instead, you train a whole new generation of researchers,” said Psychology Professor David Klahr, the PIER program coordinator.

Another major component of the university’s strategy to bridge the gap between university research and K-12 and college classrooms is the Pittsburgh Science of Learning Center (PSLC), jointly launched by Carnegie Mellon and the University of Pittsburgh with a $25 million grant from the National Science Foundation. At the heart of the center is a research facility called LearnLab where scientists from around the world can run innovative studies in real classrooms and use volumes of data from student use of educational technology to advance our understanding of how people learn.

A key focus is on understanding “robust learning” that leads to knowledge students retain, apply to new situations and put to use to learn more quickly in the future.

This research comes at a pivotal time for K–12 education. Never before have public schools been under more pressure to boost student achievement. The federal No Child Left Behind Act requires schools to demonstrate “adequate yearly progress” on various standardized tests. But integrating quality educational research into public school curricula is not easy. Too often, classroom research lacks scientific rigor while sophisticated, highly refined laboratory experiments have little real-world relevance.

“This is an idea whose time has come,” said Kenneth Koedinger, an associate professor of human-computer interaction and psychology at Carnegie Mellon and co-director of the PSLC. “We are not getting the high-quality, useful research we need to meet federal goals to improve education. LearnLab will provide a much-needed infrastructure to produce such research.”

LearnLab scientists initially are using two high school and five college-level courses as a basis for their research. The PSLC will invite schools in the Pittsburgh area and across the country to participate as “research schools” and serve much as research hospitals do for medical research.

Not that Carnegie Mellon is starting from scratch. Koedinger, for example, was one of the developers of software systems, such as Cognitive Tutor, that provide students with individualized instruction in a specific subject. These intelligent tutoring systems grew out of the pioneering work of John R. Anderson, the Richard King Mellon University Professor of Psychology and Computer Science, who began developing the system in the 1980s.

In the early 1990s, the Pittsburgh Public Schools piloted Cognitive Tutor Algebra, and last year the district adopted the program as its algebra 1 curriculum. The U.S. Department of Education has designated Cognitive Tutor an exemplary program and named Cognitive Tutor as one of only five off-the-shelf middle school mathematics programs whose effectiveness had been demonstrated through research.

“Way back in 1992, we had huge numbers of kids who were bombing out in algebra and they didn’t get any further than that. Algebra was the academic gatekeeper,” said Jacklyn Snyder, a veteran teacher and the mathematics curriculum specialist with the Pittsburgh Public Schools.

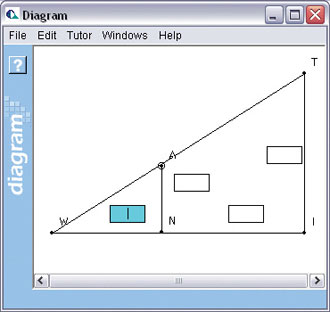

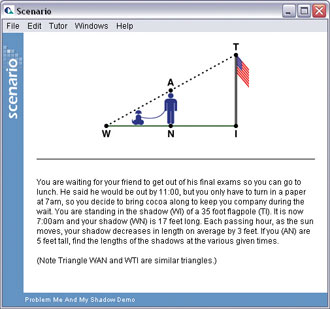

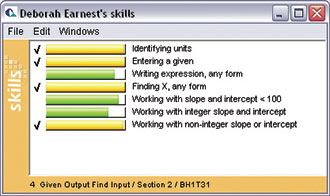

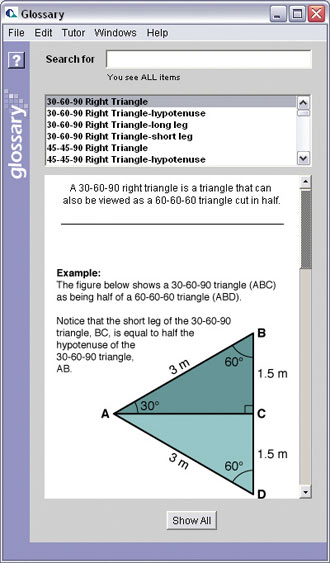

The technology that drives intelligent tutoring systems is grounded in research into artificial intelligence and cognitive psychology, which seeks to understand the mechanisms that underlie human thought, including language processing, mathematical reasoning, learning and memory. As students perform problems using these tutoring systems, the program analyzes their strengths and weaknesses and on that basis provides individualized instruction. Intelligent tutoring systems do not replace teachers. Rather, they allow teachers to devote more one-on-one time to each student and to work with students of varying abilities simultaneously.

“That differentiated instruction enables the kids who are able to go faster to do more, and it still satisfies the needs of kids who need remediation,” Snyder said.

Snyder said Cognitive Tutor has no parallel in other educational software. It helps students to understand the practical applications of algebra better than conventional teaching methods, and it more clearly illustrates the connections between concepts, she said.

“The students like it because they feel they are working at their own pace and they get feedback on what they are doing. If they understand something, they get to move onto new problems,” said Diane Briars, program officer for mathematics and science in the Pittsburgh Public Schools.

The technology has many educational applications-for example, Elizabeth Jones, head of the Department of Biological Sciences, was named a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Professor in 2002 and awarded a four-year, $1 million grant, half of which was to be used to develop a genetics cognitive tutor. Work on developing the genetics cognitive tutor also is bolstered by two substantial federal grants to Jones, Koedinger and Albert Corbett of the Human Computer Interaction Institute.

Researchers credit the innovation and interdisciplinary culture at Carnegie Mellon for the university’s success in these varied initiatives. Even without a graduate program in education, Carnegie Mellon is revolutionizing the tools and practices in K-12 classrooms.

Related Links:

Program in Interdisciplinary Educational Research

Carnegie Learning Inc.

David Klahr

Pittsburgh Science of Learning Center

Kenneth Koedinger

John R. Anderson

Open Learning Initiative