|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|||

|

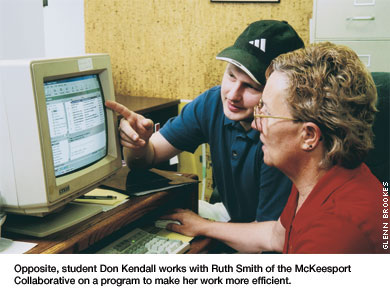

Off-campus Ventures Courses Take Students Into Community Service Students strive to leave a lasting change when helping in the community. By Mary Niederberger Two years ago, when Ruth Smith became project coordinator of the McKeesport Collaborative, she spent a lot of time stuffing envelopes with information for her member organizations. The collaborative is a joint venture of about 40 nonprofit agencies that help women affected by substance abuse with programs to strengthen families and encourage education and self-sufficiency. Though a computer sat on the desk of Smith's tiny office, she couldn't figure out how to use it. Recently, however, a computer consultant started to visit her once a week. First, he taught her how to use e-mail to send out information. That eliminated her need to stuff 107 envelopes every few weeks. Then he helped her to set up a Web site for her organization: www.mcollaborative.org. One might wonder how much the consultations cost the nonprofit organization whose only paid staff member is Smith. The answer: Nothing. The computer consultant was actually Carnegie Mellon junior Don Kendall, a business major and computer science minor, who spent time with Smith as part of his work for the course Technology Consulting in the Community. Kendall is one of 110 students who have worked with 87 organizations since the course was first offered in the spring of 1998. The course is one of about two dozen offered at the university that include community service as a major component. Instructors Joseph S. Mertz Jr. and Kathy L. Schroerlucke developed the course so students could apply their classroom skills and knowledge to community projects and organizations. Moving toward society's real needs Mertz says that the Carnegie Mellon students who take community service courses are better prepared when they reach the work force "because of their demonstrated ability to take education out of the theoretical classroom and use it to address society's real needs." The idea of doing public service through academic courses is not new to Carnegie Mellon. Courses in architecture, engineering, and information systems have long included service projects. Carnegie Mellon maintains a list of 300 nonprofit organizations and schools that could benefit from student consulting services. The list grew out of Mertz's technology consulting course. Departments and schools offering community service courses include Art, Architecture, Computer Science, Drama, English, Engineering, History, Modern Languages, Music, Philosophy and Social and Decision Sciences. In 1993, the course Tutoring, Mentoring and Role Modeling prompted the formation of the East End Tutoring Program, now a permanent volunteer organization on the Carnegie Mellon campus, says Mertz. The program offers students who take the course as an undergraduate elective the opportunity to get college credit for their tutoring services in math and reading at three elementary schools and two middle schools in the city's East End. It also allows other students to work as volunteer tutors or those who take the course to continue their service after the course has concluded. Since the beginning of the program, 210 students, staff members and alumni from Carnegie Mellon have volunteered with the program, logging more than 6,200 hours with 425 children. Last spring, 45 students volunteered as tutors. Though not every course is designed to create a permanent effort in the community, the projects students work on are designed to leave a lasting effect on the organizations where they help out. Projects at community partner sites are chosen on the basis of whether or not students can make an impact. Students are instructed to keep their efforts focused on specific areas.

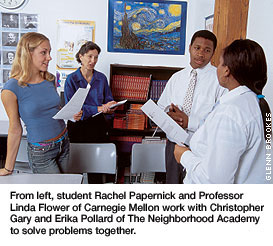

Play's the thing with helpful sting Linda Flower, an English professor, teaches The Rhetoric of Making a Difference, a course in which students use language and inquiry to help solve problems that may exist inside organizations.

Last fall students brought out the voices of nurse's aides at the Lemington Center in the Lincoln/Larimer area of the city, who were frustrated about being overworked and understaffed. The center is the nation's oldest African-American nursing home. In the spring, Flower's students captured the voices of eighth and ninth grade inner-city students at The Neighborhood Academy, a newly created alternative school in Garfield for students who showed promise but, for a variety of reasons, didn't succeed in the Pittsburgh Public Schools. The students voiced frustrations over the new school, where their behavior and schoolwork are monitored much more closely than in the past. At the Lemington Center, students interviewed nurse's aides as they did their jobs and then used the information to create skits with dialogue that outlined problems facing the workers. Carnegie Mellon students performed the skits in an 18-month series of Carnegie Mellon Community Think Tanks that included all levels of workers at the center and elsewhere. Participants discussed alternatives and solutions. The Carnegie Mellon students collected the dialogue and alternative solutions in a 40-page Healthcare Findings, published by the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at www.cmu.edu/thinktank. One skit portrayed an experienced nurse's aide becoming short-tempered with a new nurse's aide she was trying to train on a day when the wing they were working on was short-staffed because another aide didn't show up for work and didn't call to report off. Among the solutions discussed was for all levels of the staff to work together to assess and carry out the morning's priorities when short-staffing existed. The group also talked about finding ways to help the nurses's aides, mostly females, with the problems keeping them from getting to work, such as day care or transportation. Mel Causey, president and CEO of the Lemington Elder Care Services, the parent company of Lemington Center, says the skits allowed employees to see their input considered in the decision-making process and to view the problems without being directly connected to them. "The skits were very, very accurate, and the employees had the opportunity to see the direct implications of their comments," says Causey. "That was very valuable because usually when we had meetings and we talked to staff about concerns and we developed strategy for addressing them, the staff didn't necessarily see their comments as part of that." At The Neighborhood Academy, Carnegie Mellon students spent the spring semester meeting with the academy students in small groups. Out of those discussions, the Carnegie Mellon students were able to identify two major issues the teens faced:

"Hopefully, there will be better communication between the students and the adults in their lives, their principals and teachers," says sophomore Rachel Papernick, one of Flower's students. "When they [the students] do talk, it's complaining and yelling. They don't do much reflection. Maybe by watching the dialogue or being separated from it, they might be able to step back and see their situation differently." Papernick's comments came after a particularly raucous session with two groups of students who spoke over each other and fumed about their frustrations with the increased expectations of them at the new school. The Carnegie Mellon students tried to keep the session orderly by asking the students to pass a chalkboard eraser to each other to be used as a mock microphone. Only the student holding the eraser was supposed to speak. But students grabbed the eraser from each other or simply ignored the rule and blurted out their anger over rules, disciplinary procedures, dress codes and academic demands. During those sessions, the academy students appeared far more interested in venting their frustrations than in discussing solutions. "We are trying to get them to realize that they have already made decisions by the way they have reacted," says Papernick. In the final Think Tank, however, with students, teachers, the class and visitors, including Carnegie Mellon Trustee Judge Justin M. Johnson, everyone began to explore solutions to the problems of getting and giving respect that were posed in the skit, Flower says. "The dialogue, collected by the class, opened up some strong alternative decisions—based this time on reflection," she says.

Both sides benefit in service activities In the Technology Consulting in the Community course, the goal is to help the leadership of nonprofit organizations become literate in the computer technology they have available, Mertz says. Students attend one 80-minute class per week and then spend three hours with a community organization. "They [nonprofit leaders] may have some equipment and some ideas. The student's job is to turn that into a program and to figure out ways to maintain it in the future," Mertz says. That's exactly what happened for Smith at the McKeesport Collaborative. After a couple of meetings with Kendall, the two were able to pinpoint what she could learn in the course of a semester that would be of lasting value. Specifically, she needed a better way to communicate and promote the collaborative. The importance of mastering e-mail became obvious when Smith told of her envelope-stuffing activities every few weeks, a task that took several hours because different information was sent to different members. "There was no reason for her to be stuffing all of those envelopes," says Kendall. On a recent Monday afternoon, the two sat huddled together over the computer working out details of the Web site they were composing. Kendall, wearing a baseball cap and running shoes, looked every bit the college student. But to Smith, his services were as valuable as those of any high-paid corporate consultant. "This has been an absolutely wonderful experience," says Smith, who took an introductory computer course at Community College of Allegheny County in preparation for working with Kendall. "It has reduced my stress level so much by helping me to get things done so much more quickly." She especially appreciated the patience Kendall showed her since it was clear his knowledge of technology was vast and hers, minimal. "He never made me feel stupid," she says. Kendall says he could see that Smith was learning from his instruction and that he was making a lasting impact on her organization. He says he also would be pleased to be able to add consulting to the list of professional experiences on his resume. In addition, Kendall says he enjoyed the change of pace of being the teacher rather than the student.

"One day a week, I get to come check on someone else and make sure their homework is done."

> Back to the top > Back to Carnegie Mellon Magazine Home |

|||

|

Carnegie Mellon Home |

||||

Flower's students study the strategies of such American pragmatists as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Martin Luther King Jr. and Cornel West. They learn how to engage others in what Flower terms "intercultural inquiry that solves a problem. They bring out the voices of people who are often not brought into decision making or problem solving as partners," Flower says.

Flower's students study the strategies of such American pragmatists as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Martin Luther King Jr. and Cornel West. They learn how to engage others in what Flower terms "intercultural inquiry that solves a problem. They bring out the voices of people who are often not brought into decision making or problem solving as partners," Flower says.