Bowei Gai, like many serial entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley, is a restless sort. In 2007, while finishing up his master’s degree at Carnegie Mellon, he co-founded mobile photography app Snapture. His second startup, CardMunch, a business-card transcription service, was bought by LinkedIn, early in 2011, reportedly for seven figures. He then led a transition team to integrate his company into the fold of the popular professional-networking giant.

By late summer, he found himself exhausted and in need of a vacation. On an impulse, he looked for cheap flights to China, where he had lived as a child. Almost as soon as he booked a trip for the following week, he got anxious. What would he do with himself for nearly a month? Then he realized that he knew nothing about China’s startup scene. Great time to start learning.

Before he packed his bags, he worked his network to get introductions in China to investors, lawyers, the smallest entrepreneurs, and a businessman worth billions. Once there, he soaked up everything he could about the startup ecosystem in that rapidly expanding economy.

Back home in his “sideways house” in San Francisco—he lives on one of the city’s most crooked streets, which gives his house the illusion of sitting askew—he wrote up his observations to send to those who had helped him network. At 2 am, he clicked send. By the time he awoke six hours later, he was a folk hero. Someone had posted his PowerPoint file, titled The China Startup Report. Already it was on the front page of SlideShare—the YouTube of slideshows—and had gone viral in the United States and China.

“The reason it became so popular is that I didn’t write a detailed report with all the numbers and pages of facts because people don’t read that,” says Gai of his 15-minute crash course. “It’s a thin layer of information that covers lots of broad topics.” For instance, he reported that the fundamental rules of the Internet don’t apply in China. The Chinese do not pay for software, only physical goods and games. “Microsoft would not survive there,” he wrote. As for his opinion on competition, he doesn’t beat around the bush: “All are vicious, many are unethical, some are illegal. It’s a dog-eat-dog world in China. For example, companies can buy customers’ favorable reviews and reviews to destroy competitors. Intellectual property protection is something the government is pushing for, but in practice it’s virtually non-existent. Competing in China requires a different mindset.”

Gai’s Silicon Valley credibility contributed to why the report was well received. But, perhaps most important was his brutal honesty. “I wasn’t planning to share this with the world,” he says. “This was a private report for my friends.”

Friends mean a lot to Gai. In fact, the reason Carnegie Mellon has been one of the keys to Gai’s success is not only because of the education (he earned his BS in 2006 and MS in 2007, both in electrical and computer engineering) but also the friendships. His CardMunch co-founders include Sid Viswanathan (E’06) and venture capitalist Manu Kumar (E’95, CS’97, TPR’99). Even his first CardMunch intern, Sudeep Yegnashankaran (E’08, ’09), was a Carnegie Mellon student. “I did end up leveraging my Carnegie Mellon network because these are the people who you trust to have a very good basic training,” he says. “You can easily check their credentials through your friends. People can vouch for them.”

Viswanathan remembers his first impression of Gai. “He’s fearless,” he says. “Whatever it is,” he laughs, “Bowei’s plan will be some version of taking over the world.”

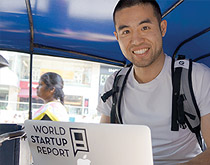

Gai’s latest project actually takes him all over the world. He’s not in it to make money. He’s made plenty for the time being. But his China report led him to reflect on how little is known about global startup cultures. So last January, he kicked off the World Startup Report, his ambitious plan to document startup ecosystems by traveling to 29 countries over nine months. Every five to ten days, he says, he “parachutes” into a new country and opens his email to a 10-page schedule. He’s preaching the gospel of the startup, acting as a facilitator, and helping entrepreneurs in each county network with one another.

Benjamin Joffe, who identifies himself as a startup therapist and angel investor, traveled with Gai across India. “I remember telling Bowei he also had to take time to have fun and try local things,” he says. “He was so focused on doing a great job, filling up all his days that I thought he might burn out. You can take Bowei out of the Valley, but it’s hard to take the entrepreneur out of him.”

Gai took Joffe’s advice to heart. Among their cultural experiences were a rooftop yoga session, meditation in an ashram, and Bollywood dance lessons.

It’s been a life-changing experience, Gai says: “No matter where you are, there’s innovation. You can be in the middle of nowhere, Nepal, and build a million-dollar company.”

He says he’s also realized that the end result of innovation doesn’t necessarily have to be the next Facebook. “A lot of these places worry about a completely different set of problems—like electricity and running water. These past months, I’ve met about 5,000 entrepreneurs, teaching them what I know and helping them see how they can tackle problems in their own country. I hope I’m inspiring a new wave of entrepreneur.”

Sally Ann Flecker is an award-winning freelance writer who is a regular contributor to this magazine.