The audience settles into their seats. It is a day of celebration at Carnegie Mellon, and as with other ceremonious occasions, a musical performance is planned in the College of Fine Arts Alumni Concert Hall. Yet, this performance and this occasion differ a bit from what most might expect. The music for this day is 4’33” by avant-garde composer John Cage, who pressed the boundaries of how we regard art. His thinking is perhaps best summarized in his “rules” for students and teachers: where the tenth and final rule reads:

We’re breaking all the rules. Even our own rules. And how do we do that? By leaving plenty of room for X quantities.

The “X quantities” are variables, the world of probability and uncertainty. Cage’s signature composition, 4’33”, certainly breaks the rules and leaves plenty of room for the uncertain. It’s four minutes and 33 seconds of musicians playing not one note—and yes, there is a score.

To add a level of Cage-like uncertainty, making sure neither artist nor composer has any impact on the piece, random chance will determine whether this scheduled performance will even take place on this day. A man walks onstage with two performers and rolls a backgammon doubling cube; it comes up 32, one of the numbers that will permit the performance to take place. (Had the number been 2, there would have been no performance.)

So, the performers situate themselves at the piano. For four minutes and 33 seconds, the room is mostly quiet, with the stillness interrupted briefly by audience laughter when one performer turns a page of the music, the score with no notes. At its conclusion, the man who rolled the cube returns to the stage and discusses Cage’s revolutionary perspective on art and his willingness to press boundaries and new frontiers:

“To my way of thinking, art has been as critical as science and engineering in moving humans along the probabilistic path we travel. We would not be human without it.”

Interestingly, the words come not from a music or art professor. Rather, the speaker holds a doctorate in computer science, with a professional history deep in Silicon Valley. Yet, it seems fitting that someone from the world of visionary technology has a taste for John Cage, for the world of chance—for art willing to experiment at the frontiers. The worlds of art and of technology forever dwell at the frontiers because they are in the business of innovating, of breaking today’s rules in order to fashion tomorrow’s creations.

The speaker, Ed Frank (S’85, Trustee, P: CMU’06) has more to say. The Apple VP has personal experience with the comingling of technology and art. His wife is Sarah Ratchye (A’83, P: CMU’06), an artist who has a history in the sciences and a deep interest in the technological achievements of modernity.

Frank, too, is knowledgeable about the subject of art—from the visionary work of the Impressionists to video artist Nam June Paik; and, as he considers the art in his home, it’s clear he has a very personal relationship and attachment. Ratchye, in turn, has a deep appreciation for the sciences. Initially a trained geologist, her artwork has focused a great deal on the Space Age and on the fervor that for many years fed the race into space.

The couple met at Stanford University and then continued their studies at Carnegie Mellon. Frank followed his technological interests into the emerging discipline of computer science. Ratchye, however, turned herself over to the arts. Although she had spent several years as a field geologist in Utah and Wyoming, the world of art resonated with her; as she says, “I really liked being around artists more.”

She focused on ceramics, molding clay from the earth she once studied, but eventually she moved into her primary discipline of icon painting, which is a pictorial illustration of a subject. “People have learned how to look at their reality through icon painting,” she says. “It tells stories visually.”

This line of artistic reflection has led to a worthy career. Her work has been exhibited in numerous one-person and juried shows and is in private collections in the United States and Australia. She was also a member of the board of trustees of the San Jose Museum of Art and chair of its collections committee.

Meanwhile, Frank, prior to his years at Apple, was pursuing a path as an entrepreneur in the technology industries of California, building a series of start-up companies and assembling an impressive roster of patents. All the while, his passion for art has remained a steady presence, as much a part of his life as his work. He says his parents taught him such an appreciation early in his life; and, through his wife, he maintains a busy schedule filled with arts exhibitions, both local and international. He considers art as important as science in transforming humanity, saying:

“It is the artist who makes revolutions happen.” He even has a sense for artistic humor, observing that he would like to be able to perform 4’33”, but “unfortunately never learned to play the piano.”

The couple’s attachment to art expresses itself through the diverse collection of artwork that fills their home. In thinking about their collection, Frank refers to the chief art critic for The New York Times, Michael Kimmelman, and his book The Accidental Masterpiece: On the Art of Life and Vice Versa (Penguin, 2005). Kimmelman observes that people long to own and connect with something unique and that connection is part of life’s richness, as he writes: creating, collecting, and even just appreciating art can make living a daily masterpiece.

The words well suit Frank and Ratchye, who believe that people should delight in the fruits of imagination every day. As Frank says he observes, only half-jokingly, when entering the homes of friends: “These people need some art.”

The same thinking transfers to thoughts on arts institutions. For some, art museums and galleries present an interesting paradox in that they house collections that are considered to have great value but, in reality, have no intrinsic practical worth. Neither Frank nor Ratchye agree with that paradox. He calls museums and galleries our “temples” to art that inspire us in so many ways, including the innovation that takes place daily in settings such as Silicon Valley.

How then do Frank and Ratchye, technologist and artist, choose to make an impact that celebrates their love of art and their inclination to bridge the synaptic space between it and technology just as they have done in their marriage? The answer to that question is what they have come to announce to the fanfare of John Cage.

A second lesson that Frank says he learned from his parents was the importance of philanthropy, and as his wife reports, his first response to his business success was: “I’m dreaming about how to give this money away.” Acts of philanthropy are indeed creative endeavors in their own right, and Frank and Ratchye are keen to communicate that philanthropic gestures take forms as varied as the creative minds that practice them.

With such a notion in mind, their interests turned to a Carnegie Mellon venture: the STUDIO for Creative Inquiry. Golan Levin has served as director since 2009. He is dedicated to helping his students, colleagues, and visiting fellows see the possibilities inherent in developing provocative work that explores more than one area of study—a laboratory for atypical, anti-disciplinary, and inter-institutional research at the intersections of arts, science, technology, and culture. It’s a place where pioneering ideas like those in the spirit of the late John Cage are nurtured. It’s that kind of culture that Frank and Ratchye have recently chosen to support through a $1 million endowment.

At the Alumni Concert Hall, it’s revealed that the studio will be now called the Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry in honor of the couple’s generosity. Levin describes the gift as visionary because, although it is easy to give to what already exists, it requires courage to support things that have yet to be made.

In part, the endowment will encourage the creation of innovative artworks by the faculty, staff, and students—works that can be described as “thinking at the edges” of the intersections of disciplines. The Frank-Ratchye fund will support at least five projects per year, which will be selected by a committee twice annually. Indicative of Carnegie Mellon’s dedication to pursuing innovation and inspiration, this endowment will encourage artistic interpretation and exploration among all educational programs at the university. Participants do not have to be affiliated with the university’s College of Fine Arts to work within the STUDIO.

At the studio naming, one last speaker, Ratchye, steps to the stage. She offers this advice:

“I encourage the students and faculty to think expansively. Experiment. Take many leaps toward a dream. Fail. Be brave. And create.” In the case of Frank and Ratchye, these intersections weave the fabric of their daily lives.

Andrew Swensen serves as adjunct faculty to the College of Fine Arts and the Master’s Program in Arts Management of Heinz College. He has written for both scholarly and journalistic publications, and he works with Carnegie Mellon students to present an online journal on the arts, The Muse Dialogue.

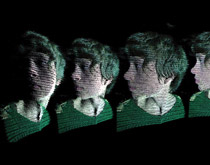

page 1 image: 3D Scanning by Kyle McDonald

page 2 painting: Moon Walk, (Ratchye titles her works phonetically) oil on canvas, 48'x36", 2007

page 3 photo: Directed by STUDIO Fellow, Grisha Coleman, "Echo::System" is a performance of 'constructed' environments with live music, dance, live video and electro-acoustic design. Performers and viewers co-exist within sensory-rich, immersive environment, witnessing stories that unfold as a way to re-examine contemporary urban life. Natural habitats such as the bottom of the ocean floor, an open praire land, a volcanic island, a desert, a forest, provide the information from which the team of collaborators develop physical, virtual, and mythological material systems to create alternative environments.

Related Links:

Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for creative Inquiry

Inspiring Creativity

Inspire Innovation