In the early 1960s, Harvard Square, steeped in tradition, had just undergone a major transformation. An entire city block was razed to make way for the Holyoke Center, which was designed by Josep Lluís Sert, Harvard's dean of the Graduate School of Design and a renowned architect and urban planner.

University officials had big plans for the penthouse of the multi-purpose, 10-story structure. From that lofty spot, a host of dignitaries would attend formal dinners, various board meetings, and other high-profile events. It was only fitting that one of the most influential artists of the time would be commissioned to provide the room's artwork.

Harvard had selected American painter Mark Rothko, who helped bring the Abstract Expressionist movement to the forefront of modern art in the postwar years. His experiments in color, scale, and proportion helped drive the shift in art away from representational images and toward the abstract.

Working from his New York studio, Rothko completed five murals for the top floor of the Holyoke Center. The mystifying, somber paintings stood almost nine feet high and filled the wall space of the penthouse. A triptych, 33 feet wide, occupied the entire west side of the room. The fourth and fifth panels hung at each end of the east side. Windows spanned the other two walls. The massive canvases came alive with darkly luminous brushstrokes of crimson paint, creating stacks of rectangles that seemed to float in a hazy sea of color.

Day after day, visitors streamed into the "Rothko Room" to behold the famous murals. Soon, though, a noticeable change began to take place. The lush, red-toned background of the paintings started to fade, leaving behind splotches of dismal purple and stonewashed blue.

To shield the Rothko murals from the direct afternoon sun, building staffers were instructed to keep the curtains drawn during daylight hours. Yet, only a steeplejack on the spire of Harvard's Memorial Church could rival the splendid view down the Charles River toward Boston. With the drapes often left open, it took less than five years for the sunlight to scorch the paintings, completely leeching away the brilliant color so fundamental to their grandeur. The damage became an embarrassment to the university.

The unforeseen catastrophe fell into the hands of Paul Whitmore, a young physical chemist who joined the staff of the Harvard University Art Museums in 1986. His job was to use his scientific expertise to help art conservators at the institution prevent and repair damage to the cultural treasures in their collection. In this role, he had to determine what went wrong with the Rothko paintings, which were now in storage, and whether displaying them in an upcoming museum retrospective would cause even more harm. The exhibit planned to recount the story of the murals as a kind of mea culpa for the university.

Whitmore's chemical analysis revealed that Rothko created his paintings with an unstable red colorant—called Lithol Red—that was extremely vulnerable to the high light levels in the Holyoke Center. "The kind of pigment you might find in the Sunday funny papers," he muses. He calculated that displaying them for a short while in a dimly lit museum shouldn't cause further damage.

The plight of the Rothko murals began to haunt Whitmore. "There I was doing postmortem on paintings that were destroyed during just a very brief period in our care," he says. "I couldn't help just shaking my head and asking myself how in the world we could have let this happen to our most precious things and how we could do better."

One person trying to answer those questions was chemist Robert Feller. In 1950, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., set up a fellowship in Pittsburgh at the former Mellon Institute for Industrial Research to advise the museum on preservation and curatorial issues. The laboratory, under Feller's leadership, was funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation—its primary financial sponsor for more than a half-century.

"This was a very new field, and as it turned out, I was really the only PhD chemist in America doing this kind of work," says Feller, now 88. "I was very lucky in this life to have had the great privilege to be a pioneer."

Feller's early experiments focused on natural and synthetic picture varnishes, color, and the damaging effects of light exposure. Later he began to explore paper degradation and to study the chemical stability of acrylic polymers.

In 1976, the National Gallery ended the fellowship. The program became the Art Conservation Research Center at Carnegie Mellon with a mission to figure out why artists' materials deteriorate and how paintings and other art objects can best be treated to slow or prevent degradation. Ideally, the center's research would help museums, libraries, and archives preserve and restore their cultural property.

"Conservation science is one of those peculiar fields that just grabs people and engages them when they find out about it," Whitmore says. "You get struck by the magic of it."

It's the romantic—and humbling—kind of magic that comes from holding a Van Gogh in your hands or taking a scalpel to a centuries-old Raphael. Or from the strange intimacy of trying to get inside Rothko's mind to discover why he used light-sensitive pigments for murals intended for a sun-drenched room. Was it accidental, or was the artist making a statement about mortality and impermanence?

"It's almost that direct connection with the genius at the other end of the masterpiece," Whitmore says. "You are engaged in the technical discipline you trained for, but you are doing the scientific research on objects that have so much backstory that it makes your work absolutely exhilarating."

Whitmore discovered his interest in conservation science as an undergraduate at the California Institute of Technology during a lecture from a visiting researcher about piecing together fragments of ancient marble sculptures using trace element chemistry. “I remember thinking, ‘That would be a really wonderful way to spend a life if I could do the science that I’m good at and help bring a little more beauty into the world in the process,’” he recalls.

However, education programs for conservation scientists simply didn't exist at the time. After earning his doctorate in physical chemistry from the University of California, Berkeley, Whitmore honed his scientific skills through a postdoctoral fellowship at Caltech and a contract project for the Getty Conservation Institute in Los Angeles, investigating the effects of air pollution on art. Working at the Harvard museums for two years then gave him on-the-job training in art conservation and history.

In 1988, following nearly four decades at Carnegie Mellon, Feller decided to retire. In that time, he published more than 100 research papers and earned a reputation as one of history's most accomplished conservation scientists. His center had become—and remains—the only one of its kind in the nation not affiliated with an art museum. That independence afforded him the luxury to do the kind of basic research that museums typically don't invest in because it takes too long and costs too much.

"What makes the Carnegie Mellon lab so unique is that they are looking at fundamental issues of conservation," says Jim Druzik, senior scientist at the Getty Conservation Institute. "Ultimately, that has proven to pay enormous dividends in terms of prevention."

The freedom bestowed by working in an academic setting is largely what drew Whitmore to Carnegie Mellon to assume leadership of the center when Feller left. He set out right away to focus on the challenging conservation problems that were emerging in modern art, partly due to the wide range of novel materials being used—everything from synthetic organic polymers to Campbell’s soup cans.

Contemporary artwork usually arrives at museums in near-pristine condition. Yet so little is known about the life span of these new art objects; Whitmore wanted to learn how to identify potential trouble spots before they surfaced. That way, museums could make fact-based decisions about whether they need to treat certain pieces of art with greater care by moving them periodically to dark or cold storage or by adjusting the amount and quality of light they receive.

Ever mindful of the Rothko disaster, Whitmore tried for several years to use traditional chemical analyses to build a comprehensive library of pigments categorized by their light sensitivity. His experiments proved unsuccessful. "I was throwing up my hands because there just wasn't the technology to make that subtle distinction for the hundreds of pigments out there," he says.

Then, during a scientific conference in 1994, Whitmore watched a manufacturer show off a new digital spectrometer that could track colors of a material in almost real time. He dashed back to his hotel and sketched his ideas on a napkin. The device he imagined would shine a very intense light on a tiny area of a colored art object. If the material was prone to fading, exposure to the light would cause a subtle color difference invisible to the naked eye but detectable by the fast-acting spectrometer.

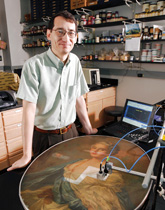

Two years later, Whitmore freed the time and grant money needed to build his instrument and make sure it would be safe to use on even the most valuable and irreplaceable works of art. Next he loaded the "micro-fading tester" in the back of a truck and embarked on a road trip—his self-described "infomercial"—to give demonstrations at museums from Chicago to Boston.

"As soon as I learned that Paul had this piece of equipment, I knew we somehow had to get one," says James Coddington, chief conservator at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City, which built its own micro-fading tester based on Carnegie Mellon's prototype. "Now we can get actual measurements of the light sensitivity of a work of art and use that information to make informed choices about the care of our collection."

And MoMA isn't the only one. Getty's Druzik says he liked the micro-fading tester so much, "I bought two of them." At least 15 other major museums in the United States and Europe also rely on micro-fading testing to take the guesswork out of determining which objects in their collections are most susceptible to damage—a gratifying outcome for Whitmore. "You could say I have fulfilled my career ambition by preventing the next Rothko accident from happening," he says.

Whitmore and his eight-person scientific staff are now using the micro-fading tester to study the notoriously light-sensitive pigments in Japanese woodblock prints. They also are developing a software program to translate the numerical output from the tester into easier-to-interpret digital images that simulate future fading.

Studies of additional material performance and conservation treatments are also ongoing, and a new research project is now under way using silver nanoparticles to build a sensor that could detect volatile gases emitted from works of art as they age.

Beyond its ambitious research agenda, the center is educating and training tomorrow's art conservation researchers through a $3.87 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. As part of the initiative, Whitmore was recently appointed as a research professor in the Department of Chemistry and, for the first time, will serve as an advisor to PhD students. The center—located at the riverfront Pittsburgh Technology Center—is now part of the Mellon College of Science. The goal is to better integrate conservation science, largely confined within museum walls, into the mainstream academic community. Doing so, Whitmore believes, will lead to new talent and funding and possibly more scientific breakthroughs to preserve the world's cultural heritage.

"I don't want to get too weepy about it," he says, "but just as I'm thrilled by all of the things that are centuries-old, future generations are going to be thrilled about the art we make now, if we can just get smart and devote enough resources to caring for it."

He alludes to Harvard's Rothko murals to emphasize his point. Somewhere, outside Boston, the murals remain rolled up in a dark storage locker like old rugs stashed in an attic, perhaps never to be seen again. By contrast, the late artist's work White Center sold for $72.8 million last year at Sotheby's New York.

Jennifer Bails is a freelance writer and former award-winning newspaper reporter. Her work appears regularly in this magazine.