The bus, filled with schoolchildren, sits stranded on the savanna. The driver guns the engine, but the wheels only spin deeper into the sand. They won't get anywhere this way. The children, ages 2 through 12, sit obediently, stuffed three or more to a seat. It's the hot season in Tanzania. Mama Lucy Kamptoni, the Shepherds Junior School principal and founder, holds her cell phone out the window. Although cell phones are among the few reliable forms of technology in Tanzania, the phone gets no signal. The weight of the situation begins to settle in. The children and teachers are trapped on the bus, two miles into Tarangire National Park, with no way to call for help. Outside, wild animals roam, invisible in the brush.

One of the adults on the bus looks for an upside to the situation, even while worrying that a passing elephant may use the bus as a back scratcher. This is an opportunity to talk to the students, to try to understand them, know their stories. To Stacey Monk, who is visiting Tanzania as part of an experiment of her own making, stories are the currency of change. And the students of Shepherds Junior need change.

Stories follow many paths. Some spiral, some meander, some arc. Just over a year ago, Monk cofounded Epic Change, an organization that is currently helping preserve the futures of more than 200 children. To Monk, Epic Change's story is a circle, an endless loop. Perhaps you enter that story on the Tanzanian savanna. Or perhaps you begin with Monk herself.

A self-labeled type-A personality, Monk admits to having a restless mind never satisfied with pursuing well-trodden paths. A Florida native and undergraduate philosophy major, she followed her passion for theater and performing arts management to Carnegie Mellon's H. John Heinz III School of Public Policy and Management. There, she encountered a blend of arts management, technology, economics, and public policy—providing the tools she would need to do all the things she never imagined doing.

"The combination of a public policy curriculum and a creative aspect allowed me to look at things in a way that perhaps others would not," the 2000 graduate says.

She translated her diverse education into a career in consulting, specializing in "change management." When major concerns such as the Santa Clara Social Services Agency and biotech giant Genentech planned internal changes, they turned to her to help their employees adjust. She brought to bear typical consulting tools like complex charts and diagrams, but she also used interactive plays and puppet shows to teach employees new company procedures. When she helped launch Funken Consulting with Sanjay Patel, whom she met at the Santa Clara agency, the firm was immediately successful.

Despite Monk's consulting accomplishments, she never lost sight of her love for nonprofit work, acquired during her theater management and social services experiences. "I knew my path would be to learn whatever I can and bring that back to nonprofit projects," she says. On one of many cross-country business flights, she and Patel made up their list of life goals. For travel, Africa was at the top of each of their lists. They decided right then to make the trip happen—with a twist. The pair planned a two-month trip spanning from South Africa to Egypt, but half of the trip would be spent as "voluntourists," teaching in local schools in Arusha, Tanzania.

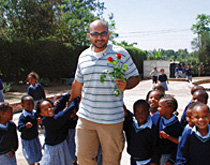

Three months later, in January 2007, Monk arrived in Africa; for the next month she was a volunteer teacher to Kamptoni's Shepherds Junior School, a pre- and primary school. Kamptoni founded the school in 2003 to address a need she saw in her community and country. World Bank statistics show that the average Tanzanian earns about $350 a year, compared to more than $44,000 in the United States. AIDS is a full-blown epidemic in the country, a major source of the nation's approximately 1.1 million orphans younger than 18, according to the United Nations.

"The three major problems that hinder our country's development are poverty, disease, and ignorance," says Kamptoni. "I said to myself, 'Let me see what I can do to fight ignorance, which will help fight the other two.'"

Kamptoni started the school with money from her boutique and small poultry farm. The school opened with 10 students. By the time Monk arrived, that number had swelled to more than 150. Many of the students are orphans or from desperately poor families; Kamptoni charges a small tuition from those who can afford it to subsidize those who can't.

Monk couldn't help but be impressed by what Kamptoni had accomplished. The teaching staff had plenty of expertise running the school, but Kamptoni still needed Monk's help—only not as a teacher. She was interested in expanding the school to ensure the children in her community received the best possible education. Monk left Tanzania with a promise to help Kamptoni; she was just unsure how she could contribute.

In August 2007, about six months after Monk returned home, she received some dire news from Kamptoni. The school's landlord was selling the land to a business developer. If Kamptoni didn't find an affordable new home for the school by February, it would be closed. For some, especially the orphans and those who couldn't afford tuition elsewhere, the chance for a high-quality education would disappear altogether.

Monk now realized how she could help. She and Patel returned to an idea that had started taking shape just before their trip to Africa. On a chilly evening in San Francisco, a homeless man had approached them, asking for help buying a pair of shoes. While they drove the man to a drugstore, Monk asked the man, "What happened?" He explained that he had once been a bicycle courier but had lost his job once he got older. He ended up on the streets, with no way to find legitimate work. It was perhaps a sadly common story, but in hearing it firsthand, Monk felt a moving, individual connection to the man and his story. She and Patel reluctantly left the man crying with gratitude at a nearby shelter, his hands full with shoes, blankets, warm clothes—and Monk's business card.

"I wanted more than anything to know what happened to that man after that day," she says. The key to helping others, she realized, is in their stories. Monk and Patel played with the concept of a nonprofit organization that would help people by utilizing their stories as resources for improving their lives.

"We thought, there has to be a way to connect people with these stories," Monk says. "If we knew people on that level, we'd be a lot further along as a society."

When Monk heard about Shepherds Junior's plight, she thought about all the stories she had gathered during her one month of volunteer work there and how they could be a solution to the school's financial problem. Monk calls Epic Change a "story-powered, pay-it-forward experiment in social innovation." The experiment's foundation is simple: Everybody has a story. Personal stories don't cost money, but Monk recognized their potential to make lots of it.

"Many aspects of our economy are based on stories. Advertising and products are sold because of their stories," she says.

Together with Patel, Monk put aside her consulting work to focus on creating Epic Change. They crafted an unusual nonprofit business model that ensures its benefits will be gifted again and again, like good stories retold. Donations contribute to interest-free loans made to motivated local leaders like Kamptoni. Epic Change then works with those leaders to repay the loan by helping them transform their stories into profitable products. Ultimately, the loan will be repaid, a perpetuating source of income will be in place for the borrower, and the repaid amount will go out as a new loan for another Epic Change project.

"We're partners and collaborators," says Monk, "not givers and receivers."

Monk believed in the model, but Epic Change had to work fast to give Kamptoni a chance to save her school. They turned to Internet social networking tools like Facebook, Twitter, and the Epic Change Web site to tell the student stories of Shepherds Junior. They blogged. They uploaded one-on-one interviews and videos of the children singing together.

Every posting focused on potential and possibility. Focusing on the negative, Monk feels is like spinning wheels in the sand. She likes to quote the father of one Shepherds Junior student: If you tell a man he is weak, he will be weak; if you tell a man he is poor, he will be poor.

So when Monk tells the story of 9-year-old orphan Glory, for example, she mentions how Glory walks over her parents' graves to go to the outhouse. She also includes how Glory missed two days of school because her shoes fell apart, preventing her from walking the miles to school. But a big part of the story is the new shoes Kamptoni bought Glory, and how Glory made a thank-you card that read: "I am so lucky."

Soon, Epic Change's model and compelling, upbeat stories had the blogosphere buzzing. Donors like California real estate broker Desh Mallik caught on to Epic Change's mission. "I liked that Epic Change wasn't just giving handouts, but teaching their partners how to fundraise themselves," he says. Mallik is now a monthly donor to Epic Change and raised nearly $1,500 from a party he hosted for the cause.

By last December, Epic Change had gathered enough donations to make its initial $30,000 loan to Kamptoni, which enabled her to purchase a plot of land and start construction for a four-room schoolhouse. Additional loans bringing the total to $250,000 are planned in the near future that will enable the school to have amenities such as bathrooms with plumbing, a playground, and a new school bus. Monk and Patel returned to Tanzania to see the land Kamptoni had selected. It's on that trip that the school bus becomes hopelessly mired in the savanna.

At last, Kamptoni manages to get a call through to the park office. Help is on the way. Outside, Patel nervously stands watch for wildlife as one of the students goes to the bathroom in the brush. Monk, meanwhile, ignores the heat inside the bus and talks to Teivin Shayo, one of the students.

The youngster fingers the holes in his school uniform sweater as he shyly answers Monk's questions. He tells her he is 11 years old and lives with his grandmother in Arusha. His parents live in Nairobi, Kenya, but sent him to Tanzania to spare him the violence that hangs over their hometown.

"There is a lot of fighting there," Shayo tells Monk. "But not with fists. With guns."

And so will begin another Epic Change story.

There will be others. Along with the stories, the students used donated cameras to be both subjects and photographers for lines of postcards and greeting cards to be sold online and in the Arusha tourist markets to begin repaying the Epic Change loans.

Monk and Patel aim to help Kamptoni get an entire line of story-inspired products on the market. The additional revenue will help enable Kamptoni to pay off her loans. Once that is accomplished, ideally in the next few years, Monk sees the recycled loans shifting to projects involving perhaps the homeless in the United States or hospital construction in Peru. She sees the possibilities branch out in countless, exciting twists of plot.

This past July, Monk returned to Tanzania for a third visit. She saw for the first time, in person, the newly built four-classroom school Kamptoni opened in March, less than 100 days after receiving the initial loan from Epic Change. The school now has more than 200 students and stories that go beyond the students—the stories of Kamptoni, of Monk, of Patel, of the homeless man in San Francisco, of all the donors and volunteers. Of you, reading this, right now.

Related Links:

Make an Epic Change Donation

Read the Blog

Watch Video

Visit the Epic Change Store

Bo Schwerin is an award-winning freelance writer based in Baltimore.