After midnight, the corridors of Carnegie Mellon’s College of Fine Arts are dim. But in the basement, room A6, lights are ablaze. Bryston Hollis, a senior electrical and computer engineering major, is in the recording studio, which has become his second home, maybe his first—even he isn’t sure which is which anymore.

Hollis describes himself as a “tinkerer.” Aside from his childhood love of taking apart small electronics just to see how they worked, he also grew up loving music. He’s been a bass guitarist since the seventh grade, and he still plays with his high school band. Using what he learns about electronics when he records music is a natural harmony between his professional ambitions and personal hobbies.

After he graduates, he will be off to General Motors to work on hardware that controls car engines and transmissions. In the meantime, he estimates he spends at least 30 hours per week in the studio, including some late nights after sessions wrap up.

He’s among the students enrolled in one of three classes taught by Riccardo Schulz, associate professor and director of recording activities in the School of Music. Schulz’s students do everything for the studio: coordinate with the musicians beforehand; set up instruments, mics, and amps; run the equipment and computers while recording; and mix and master the finished tracks.

Hollis isn’t the only non-music major in the class. Schulz describes his students as an interdisciplinary bunch from various departments with complementary interests and skills: “I can tell you story after story of people who show up at the studio, trade cell number and emails, and all of a sudden they’re in a group and they’re out there doing stuff.”

An eclectic mix of artists book time in the studio, and this week Hollis and his classmates are working with a traditional three-piece folk band from Crete that’s passing through Pittsburgh as part of their U.S. tour.

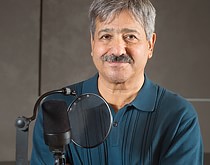

Observing the first day of the session are alumnus Nick Vlahakis, who earned a MS in mechanical engineering in 1974, and his wife, Kimi. The couple traveled to campus from Virginia to sit in on the recording session. Nick’s parents were from Crete, and he and Kimi are active in the Greek Orthodox church, so it’s no surprise the couple helped connect the band with CMU.

Observing the first day of the session are alumnus Nick Vlahakis, who earned a MS in mechanical engineering in 1974, and his wife, Kimi. The couple traveled to campus from Virginia to sit in on the recording session. Nick’s parents were from Crete, and he and Kimi are active in the Greek Orthodox church, so it’s no surprise the couple helped connect the band with CMU.

Sitting in on the session isn’t the extent of the couple’s relationship with the recording studio. Much like Hollis, Nick Vlahakis, the retired chief operating officer of aerospace and defense company ATK, was a guitarist in a high-school garage band. Although he pursued engineering professionally, he never forgot about music.

When he retired, he wanted to reincorporate music into his life, and the idea of recording intrigued him. He began dabbling and taking classes online, and his interest turned into a passion—so much so that he eventually built a small recording studio in his home, where he records local musicians pro bono.

“It’s a way to create, really,” says Vlahakis about his avocation. “That’s a release for me—to create.” Creativity was something he strove for in his engineering and management career, even writing and filming funny training videos and hiring actors to interact with his employees in character.

“To me, the better engineers were the ones who could cross over between right and left brain,” he reflects—a sentiment that will bode well for Hollis when he heads off to General Motors.

As for Vlahakis’ connection to the recording studio, the seed was planted when he returned to campus in connection with the ATK/Nick Vlahakis Scholarship and Fellowship Fund, which he created in 2003 in honor of his parents to support undergraduate and graduate students studying engineering and computer science. He happened to mention to a staffer that he had a recording studio at home, so he was ushered to CMU’s studio, where he met Schulz.

Given their common interests, the two became friends. Good thing for Schulz, because eventually he needed one. The recording studio began to fall apart. “We’d had no upgrades in the past five years—a long time in the computer world,” says Schulz. It had even gotten to the point that visiting prospective students would wonder why the studio was running software two versions out of date.

Vlahakis was aware of the woes. “I had a slightly better system [at home] than Carnegie Mellon had as far as the software,” he recalls.

The studio was starting to approach software obscurity, and, even worse, there was no emergency funding available from the School of Music to rectify the situation. It was to the point where Schulz questioned how well he could continue teaching his classes.

The studio was starting to approach software obscurity, and, even worse, there was no emergency funding available from the School of Music to rectify the situation. It was to the point where Schulz questioned how well he could continue teaching his classes.

Nick and Kimi Vlahakis provided the answer.

Last August, the couple pledged a $10,000 grant per year to the recording studio for equipment improvements and upgrades to hardware and software.

“I told Nick that the second I heard he had signed on the dotted line, I spent all of that year’s grant,” says Schulz.

The upgrades to the studio’s software and hardware were dramatic. “Everything that they’ve contributed is working so much nicer,” says Hollis. “We can focus on the music and the artists rather than worrying about problems with the computers and hardware.”

In addition to the annual support, the couple has pledged another $1 million to the School of Music as part of a living trust they’ve created to support schools that have what Nick describes as a “right brain, left brain” focus. The couple wish to ensure that future students like Hollis will be nurtured in an interdisciplinary environment and have opportunities to explore fields beyond their curricula.

In recognition of these gifts, the studio has been renamed in their honor.