Long before he made his mark on the Academy Awards in Hollywood, well before he illustrated the summer Olympic Games in Athens, two decades before he brought to life the Major League Baseball All-Star Game in Pittsburgh, and 21 years before he released Pop!, a coffee-table book featuring a retrospective of his artwork, Burton Morris thought he'd hit it big.

It was 1986, and he was graduating from Carnegie Mellon with degrees in illustration and graphic design; more importantly, he had a received a job offer with a big title. He would become the art director for a major Pittsburgh-based advertising firm. Soon he was art directing TV commercials for McDonald's foods and Tasters Choice coffees and winning ADDY Awards, the industry's most prestigious recognition.

But he found that the job entailed hiring illustrators rather than doing the creative work himself. After two and a half years, he decided to end the frustration. He quit to become art director at a smaller Pittsburgh agency. There, he planned to bring in new accounts and be the illustrator. Six months into his new job, he was working diligently to find clients, something not typically expected from an art director. The president of the firm pulled him aside. "Things don't happen overnight," he told Morris. "If you keep this up, you're never going to make it in this business."

Morris' response was to put in his two weeks' notice.

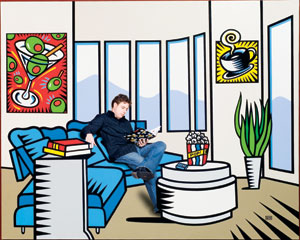

After some sleepless nights, wondering what he should do next, he took the little money in his bank account and rented a small space on Pittsburgh's North Side, which became Burton Morris Studios. He began putting his illustrations on canvases and T-shirts and transformed his drawing skills into a natural knack for painting. He had a unique style that incorporated bright, bold colors in simple designs of everyday images--everything from jazz musicians to coffee cups.

He didn't ignore marketing himself either, making sure he was represented in commercial illustrator catalogs that would land in mailboxes of corporations. "He was always busy, always working," remembers Morris' older sister, Stacey Raskin. "He was never, 'Woe is me.'" After she moved to Los Angeles in the late 1980s, she did what she could to support her brother by convincing some California boutiques to sell his T-shirts.

Thanks to Morris' marketing, calls started coming in from companies such as Sony, AT&T, Disney, and Hallmark. Although not every company chose to work with him, Morris didn't mind. He realized his reputation was growing. "Half the business was getting your name out there," he says.

In 1992, he opened his first art show at a gallery in Pittsburgh. Nationally, the Burton Morris name was spreading, too.

Then, the call came.

It was from an Absolut Vodka representative. Morris knew immediately that it was a watershed moment. Artwork commissioned by the Swedish company had become something of a modern art icon. Andy Warhol is widely regarded as starting the phenomenon when in 1985 he was commissioned to create a painting that included an Absolut bottle. Since then, Absolut ads, by a wide array of artists, have become collectors' items. In 1991, the company began its Absolut Statehood campaign, which selected an artist from each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. The artists were to create original paintings saluting the Absolut bottle and their home states, and the works would appear individually in full-page ads in USA Today and other publications.

The caller told Morris he had been selected to design the Pennsylvania ad. He would now have a national presence.

Two years later, he received another phone call, this time from his sister. She'd just sat down with her husband and kids to watch TV when she caught a glimpse of a Burton Morris T-shirt. "You're not going to believe this," she exclaimed on the phone, "but there's a guy on TV wearing one of your shirts."

The guy was David Schwimmer, and the show was Friends. But unlike with the call from Absolut Vodka, Morris couldn't fully appreciate the exposure. The fledgling comedy series had only aired six episodes. "I thought it was just a fun, lucky break."

Always a marketer, Morris on a whim called Warner Brothers, the production company for Friends. Somehow, he got through to the show's creator and producer, Kevin Bright, who told him, "I love your work. How can we get it on the show?" Two weeks later, during a West Coast trip that Morris had already planned to visit his sister, he met with Bright and toured the show's set. He worked out a deal with the producers that they could borrow some of his art. Soon, his paintings became part of the show's permanent set. Of the dozen works Morris created for the show's decade-long run, the most recognizable painting was Coffee Break, which hung framed in the background of Central Perk.

"The coffee cup symbolizes today's culture," Morris says. "Somebody might just look at it and say, 'It's a coffee cup. Big deal.' But somebody might look into it and realize the meaning behind it."

Morris' celebration of everyday objects falls in line with the pop art movement made famous by Warhol, also a Carnegie alumnus, whom Morris says "opened up the doors" for an artist like him. "He was able to look at a Brillo box or a soup can and say, 'That's a piece of art.'"

On another West Coast trip a few years later, Morris brought photographs of his paintings to David Galgano, the gallery director of Hamilton-Selway Fine Art in Los Angeles. Galgano quickly recognized the connection between Morris and Warhol, considering Morris the "new pop artist." Since then, Galgano has been Morris' West Coast art dealer and has watched numerous Morris fans become recurring clients. In the past decade, Morris has amassed an international following; collectors of his work include business moguls, Middle Eastern royalty, the Jimmy Carter Center, athletes, actors, and musicians--people such as Donald Trump, Brad Pitt, and Kanye West. "Burton is an artist of our time," says Galgano.

And then there are the events. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences' executive director called on Morris to ramp up the "bland and stale" Oscars. Morris in 2004 forever replaced the award show's formal look by introducing brightly colored banners, invitations, and an 86-foot-tall banner that hangs above Hollywood's Kodak Theatre. His art has also been featured at the World Cup Soccer Games in Paris, the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland, the Summer Olympic Games in Athens, and the Major League Baseball All-Star Game in Pittsburgh.

But no matter where Morris' art takes him, it starts out the same everyday way it did when he was a child--with a sketch. "I'm always doodling," he says. "I draw everywhere. I used to get in trouble in grade school because I would draw on the desks. I was in my own world, drawing all the time."

Allergic to oil-based paints, Morris paints only with acrylic. Each original painting is hand-drawn in pencil, then meticulously painted with several layers to flatten and even out the color. Red takes three to four coats; blue takes five. "It takes a lot of time and patience," he says.

It was Carnegie Mellon's design program, Morris says, that helped teach him patience. There, he learned to look at forms, find their most basic shapes, and simplify them. He believes that his professors--especially design school head Dan Boyarski--truly taught him how to think, a vital asset in his creative process. "At Carnegie Mellon, I never slept," he says. "One thing they teach you is to take a project and think it through. My mind is always working."

Like many painters, Morris draws inspiration from other artists. Some are wildly different from his pop style, such as the 15th-century German wood engraver Albrecht Durer. Others, like Warhol, are much more similar. Coincidently, like Warhol, Morris happened to grow up in Pittsburgh. Until he was seven years old, he lived on Beeler Street, blocks away from campus, where his parents pushed him in a stroller.

But it was at the age of three, while playing Tarzan on the monkey bars at his aunt's house, when fate seemed to intervene. He fell and broke his femur bone and was confined to a body cast for two months. He couldn't move; he could only draw. "All he needed was a pencil and piece of paper, and he was fine," his sister recalls.

As a child in the 1960s, his heroes were Spiderman, Batman, and Captain America. He loved watching cartoons and collecting comic books, and he honed his drawing ability by sketching his favorite characters. "Little did I realize that all around me was the bombardment of visual language and primary colors."

"Wherever we went, he was drawing," Raskin remembers. "In restaurants, he would go and doodle on paper place mats, and waitresses would ask to keep them."

Encouraging him to develop his natural artistic abilities, his parents sent him to art classes at the Carnegie Museum of Art when he was nine years old; Warhol had done the same thing. Before coming to Carnegie Mellon for illustration and graphic design--Warhol's major in 1949--Morris attended the university's pre-college art classes. Warhol did that, too.

But that's where the parallel between the two pop kings stops. Warhol, whose work was famously controversial, used his reputation to socialize with celebrities at posh New York clubs. And his view of his craft, as laid out in his 1975 autobiography, was more of a capitalist philosophy: Making money is art, and working is art, and good business is the best art.

Morris, meanwhile, is a self-described "kid at heart," which is evident in the cheerful nature of his work. For some art critics, Morris' upbeat outlook doesn't make enough of a statement about today's world. Once, while giving an interview in Rome, an Italian reporter berated him for being too optimistic, asking how he could be so positive when such terrible things were happening in the world. Why wasn't he depicting serious topics, such as famine or war?

"This is who I am," Morris responded. "My art is positive. Why can't you have art that's uplifting and positive, and at the same time still symbolic and meaningful? It can be interpreted and can also function in the way that people still see it in a very strong, positive light. I feel that way."

His demeanor manifests itself in other ways. Morris' mother regularly contributed to charities and reminded her children to realize how fortunate they were. Stressing respect for others, Morris' parents once took him to the School for the Blind in Pittsburgh. He realized then that although drawing was his life, some children weren't able to see the vibrant colors he loved so much. He now uses his own colors to help children. Morris donated his artwork to celebrity chef Emeril Lagasse to raise money for children in New Orleans at Lagasse's Carnivale Du Vin benefit. As the event's featured artist, his painting alone raised $65,000. Likewise, when the Andre Agassi Foundation needed an artist for its Tenth Anniversary Grand Slam for Children benefit concert, the former tennis star called on Morris, whose specially created piece, Earth Heart, amassed $125,000 for charity.

In addition to his new coffee-table book, Pop!, Morris is manifesting his art in innovative ways. For example, he recently paired up with alumnus Michael Kobold (HS'01), an internationally acclaimed watchmaker, to create a line of watches hand-painted with Morris' designs; also in the works is a pairing with the Entertainment Technology Center to mesh his work with new video game projects.

"I feel like I'm still beginning in a sense," he says. "I have so many ideas; I just want to see them come to life. I've got to live 'til I'm well over 100!"

Brittany McCandless (HS'08) is one of only two recipients of the 2007 Newspaper Guild of Pittsburgh scholarship.