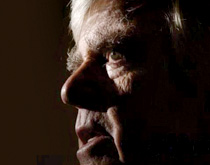

Robert Geminder walks with a purposeful stride onto the auditorium's stage. This won't be the first occasion he tells his story. In fact, he's actually lost count how many times he's taken the stage. When he begins to recount his real-life drama to the 600 or so high school students, he happens to notice a young man seated a few rows back. With black jeans, leather jacket, spiked hair, and earrings, he is impossible to miss. Is there any chance the meaning behind Geminder's words will actually reach him?

After almost an hour of rapt silence from the audience, a drained Geminder says, "Thank you," and walks off stage. As he is on his way to his car, he hears someone yell, "Wait! Mr. G, wait!" Mr. G, as the students call him, turns. It's the young man with spiked hair. He shakes Mr. G's hand and says, "I want to thank you for sharing your story. It really means a lot that you would go through it again for us."

A decade has since passed, but Geminder still remembers the encounter. "It brings tears to my eyes to think that this kid, this tough kid, chased me down to thank me," he says. "I was in shock."

Perhaps it's not so shocking given the magnitude of Geminder's story: Born to Jewish parents in 1935 in Wroclaw, Poland, Geminder's childhood became a horror story that today is still difficult to fathom. The Nazis were in power then, which meant that the Jewish community was in peril simply for their heritage. At the age of six, when most little boys would be playing outside with friends, Geminder was herded to a cemetery in Stanislawow, Poland, with 20,000 other Jews, including his family. It was at that cemetery where the Nazis killed all but 6,000 people. Geminder and his family were spared, because they were "lucky enough" to arrive at the cemetery in early trucks. Those who weren't killed became the work force for the local ghetto. After a year of hard labor and horrifying conditions, Geminder remembers how his mother, stepfather, and brother escaped from the ghetto after fearing everyone there was about to be killed.

The family fled to Warsaw, Poland, where they changed their name and pretended to be Catholics. They lived in Warsaw until 1945, when the Germans defeated the Polish Underground in the Warsaw Uprising. The Germans then forced everyone in the town, Polish and Jewish, to board trains headed for Auschwitz. Geminder says the train stopped about 100 yards outside of Auschwitz, and it was there that his stepfather had a plan. He lifted Geminder up over the open car, and the boy opened the door, enabling them to escape from the train to a nearby farm, where they hid under a trapdoor.

"My stepfather kept telling the other people on the train to get out because they were going to get killed, but they didn't believe him," Geminder recalls. "This was one situation where being Jewish may have actually saved our lives. We knew Auschwitz was an extermination camp, but the Polish people believed that it was a work camp," he says. Poland would lose 6 million citizens, about one-fifth of its population. Half of the dead weren't Jewish. Two years later, in February 1945, the Russians liberated Geminder's family. The Holocaust was finally over, and the Geminders had to somehow put their lives back in order. After moving to West Germany and finding a family member to sponsor them, they moved to the United States, specifically Pittsburgh, to start over.

"My mother and stepfather got jobs at a local Jewish nursing home, and my brother and I started school." Geminder went on to attend Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie Mellon), after working in the steel mills for several months to pay for the $340 a semester tuition fee. He was active in various campus activities, including Tau Delta Phi fraternity, where he served as president, and ROTC. He chose to study electrical engineering and graduated in 1957.

"Carnegie Tech was a very positive experience for me. I learned best how to work with people there," he says. It would catapult him into a successful career. After serving in the Army, the electrical engineer spent 37 years working at several companies in southern California. He also became international president of the Institute of Environmental Sciences and Technology Society, chair of the Marine Technical Society, and senior member of the Instrument Society of America.

He also never forgot his childhood that never was—and he began accepting invitations to speak about the Holocaust at middle schools, high schools, libraries, colleges, and other venues. "I wanted as many people as possible to hear the story, learn about the past, and never forget that 90 percent of the Jews in Poland were murdered, including most of my family members. You can read and read and read, but you can't really relate until someone is in front of you who says, "Here is what happened to me.' That is when it really hits home," he says. "Years from now, there will be no survivors alive. So it's important for people to see, feel, and understand now."

Getting his message across to the young man with the spiked hair and leather jacket, in turn, sparked a thought in Geminder. "I saw I could engage with young people who really wanted to learn." It made Geminder, at the age of 70, embark on a second career. He earned a master's degree in secondary education and now teaches math to at-risk children at Opportunities Unlimited Charter High School in Los Angeles.

For alumni who participate in the Carnegie Mellon Los Angeles Chapter events, which Geminder frequently does, he has quite a story for you.

Laurel Furlow, a former newspaper reporter, is the assistant director of on-campus programs in the Office of Alumni Relations.