Most first-year college students move more than boxes and suitcases into their dorms when they arrive on campus: they also carry worries about fitting in and making new friends. And while new friends are important for student life on campus, social scientists at Carnegie Mellon have found that they also make for a physically healthier first year at college.

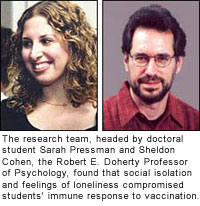

A group of Carnegie Mellon researchers have shown that first-year college students who feel lonely are protected less by the flu vaccine than other students. The research team, headed by doctoral student Sarah Pressman and Sheldon Cohen, the Robert E. Doherty Professor of Psychology, found that social isolation—measured by the size of a student's social network—and feelings of loneliness each independently compromised the students' immune response to vaccination. Their results were published in the May issue of the journal Health Psychology.

Cohen is a world-renowned health psychologist whose previous research has focused on the impact of emotions, stress and social networks on human health. This latest study could help explain why first-year students tend to visit student health centers more than older classmates, as new students can be socially unmoored as they adjust to new circumstances.

"The findings are similar to other research indicating that social ties are important for health, in part because they may encourage good health behaviors such as eating, sleeping and exercising well, and they may buffer the stress response to negative events," Pressman said.

The researchers recruited 37 men and 46 women, mostly 18 to 19 years old, during their first term at Carnegie Mellon. They got their first-ever flu shot at a university clinic and filled out questionnaires on health behavior. For two weeks (starting two days before vaccination), they each carried a palm computer that prompted them to register their momentary sense of loneliness, stress levels and mood four times a day. For five days during that period, they also collected saliva samples four times a day to measure levels of the stress hormone cortisol.

Loneliness was also measured by questionnaires at the start of the study and during the four-month follow-up. Researchers measured social networks by having students provide the names of up to 20 people they knew well and with whom they were in contact at least once a month. Blood samples drawn just before the flu shot was administered, as well as one month and four months later, indicated how well the students' immune systems mounted a response to the multi-strain vaccine.

Sparse social ties were associated with poorer immune response to one component of the vaccine, A/Caledonia, independent of feelings of loneliness. Loneliness also was associated with a poorer immune response to the same strain as late as four months after the shot. This supports the argument that chronic loneliness can help to predict health and wellbeing. The study also demonstrates that social isolation and feelings of loneliness are not one in the same.

"You can have very few friends but still not feel lonely. Alternatively, you can have many friends yet feel lonely," Pressman said.

Cohen and his team plan to study these interrelated variables to isolate the specific pathway social factors take to alter immunity. Among other things, they speculate that stress may be a go-between because loneliness is stressful and stress impairs health.

Related Link:

Laboratory for the Study of Stress, Immunity and Disease