A touch of royalty just begins to describe the life of Nancy Murrin

A young woman walks briskly to her office. The lieutenant wonders what today will bring. She remembers yesterday. She remembers Marty—a strapping marine who had just been sent to Philadelphia. He had been blinded in the war, and it was up to the lieutenant to coordinate his rehabilitation plans. She did all she could for him, but she still couldn't get him out of her mind.

Dealing with wounded soldiers wasn't easy for someone who had never thought of a military career, but a country at war changes people's aspirations. Nancy (McKenna) Murrin thinks back to what led her to Philadelphia. Two years prior—in February 1943—she joined WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) and was training at Smith College in Northampton, Mass. It was there that a marine colonel visited, looking to recruit women with business experience to join the newly established Marine Corps Women Reserves. The recruited women would replace men who were needed for combat duty.

"I was commissioned almost on the spot. I had worked for U.S. Steel, then Carnegie-Illinois Steel, as both a secretary and an interviewer for three years, so I had the experience they were looking for," Murrin remembers with pride at being among the first female marines. After training in Washington, D.C., the women were sent off to various locales. Murrin eventually ended up in Philadelphia.

She wasn't flustered by the demanding days. She says she was used to hard work and accountability from her time at Carnegie Mellon during an era when many women didn't attend four-year colleges. She pursued business studies at the university, eyeing a career with one of Pittsburgh's corporations. She remembers getting the most out of her collegiate days even without many student activities for women. Women's sports teams didn't exist, so she joined a coed badminton team as well as a rifle team. "That was the first time I ever shot a gun," she says. She also belonged to the male-dominated Mortar Board, a national honor society.

There was one honor dedicated solely to women—Campus Queen. Before the big announcement during Murrin's senior year, she and a few friends had taken the streetcar downtown to see the blockbuster film Gone with the Wind. After the show, some of her friends called the student affairs secretary to find out whether the winner had been named. It was at that moment the young women learned they were in the presence of royalty. Murrin was Campus Queen. "I was so excited," she says.

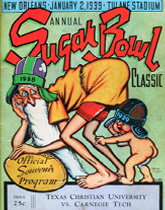

The excitement didn't end in Pittsburgh. That happened to be the year the Tartans football team would play in the 1939 Sugar Bowl in New Orleans against TCU. The game would be for the NCAA National Championship. As Campus Queen, Murrin would travel with the team along with—of course—her parents as chaperones. Murrin remembers the bowl weekend as a whirlwind tour—lunch at Antoine's Restaurant, a formal gala ball where she wore a strapless dress for the first (and last!) time, photo ops. "I had a lot of fun posing with the campus queen from TCU," she remembers. "She was a very short girl, and I was very tall, so when we had our photograph taken, I would stand in the gutter, and she would stand on the curb!"

The football team didn't stand quite as tall against the competition, losing the national championship game 15—7, but, she says in comparison to her work with injured marines just a few years later, the loss was far from haunting.

After three years in the Marines and with the war winding down, she returned to U.S. Steel as an executive secretary to one of the vice presidents. Unbeknownst to her, a name change from McKenna to Murrin would happen, too. A coworker introduced her to John Murrin, an eligible bachelor at a dinner party. The attorney left for the Navy shortly afterward, but he didn't forget the marine who was once a campus queen. He wrote her a letter. She wrote back. Three years later, they married.

It led to a new fulltime job shortly thereafter for Murrin—homemaker and mother to two children. The family settled just north of Pittsburgh, where Murrin's husband practiced law. Once her children became more independent, the drive that led her to Carnegie Mellon and the Marine Corps resurfaced. She went back to school in her 50s and earned a master's degree in library science from the University of Pittsburgh in 1967. She worked as a librarian and volunteered in the community and at the university that made her a queen.

Today, at 91 years old, she still volunteers. She also recently gave the university some priceless 1939 Sugar Bowl and Campus Queen memorabilia. Much of the collection—including programs, photos, and articles—is on display at the University Center or available for viewing upon request at Hunt Library. She say she doesn't need the mementos anymore; she remembers it all—from her education at Margaret Morrison, to being named campus queen, to doing what she could for the Martys of World War II, to raising her family.

While the world has changed since Carnegie Mellon played in the Sugar Bowl championship game, the proud alumna says some things have not: namely, a Carnegie Mellon education. "I have great respect for Carnegie Mellon and what it's doing in the world."

Laurel Furlow, a former newspaper reporter, is the assistant director of on-campus programs in the Office of Alumni Relations. She is a regular contributor to this department.